Siegfried Bettmann

Though the very first Triumph motor car did not go into production until 1923, the firm's foundations reach back to a German immigrant's arrival in England in 1884. After a year in London, Siegfried Bettmann established his own company to import various German goods. Only one of his several agencies, which dealt with sewing machines, flourished, and Bettmann hopefully turned to bicycles, which were becoming very popular.

Bettmann contracted with a Birmingham cycle maker, William Andrews, for the manufacture of cycles which his company would distribute. But what to call it? Bettmann wanted a name that made sense in all European countries, and decided on 'Triumph'. He was not long satisfied with merely distributing the Triumph cycle, however, and soon established a works in Coventry to make it.

The British Cycle and Motor-cycle Manufacturers' Union

Again Bettmann was dissatisfied - the internal-combustion engine was coming along, and he wanted to be part of the new industry. He persuaded Dunlop to inject some capital into Bettmann and Co, and in 1901 the first Triumph motor cycle was produced. A whole series of successful models followed. Bettmann, now a naturalised Briton, became mayor of Coventry and President of the British Cycle and Motor-cycle Manufacturers' Union. After World War 1 Bettmann decided to expand into car manufacture and bought out the local Dawson Car Co.

The first car to carry the Triumph Globe badge was 10-20 hp

Weymann-bodied saloon with a Ricardo - designed four-cylinder engine. Its bore and stroke of 63.5 x 110 mm provided 1393cc capacity and developed 23.4 bhp at 3000 rpm driving though a cone clutch and a four-speed gearbox. A two-seater sports version was introduced the same year. Clock, speedo, choice of leather or cloth trim, and mohair-twill top established Triumph as a firm offering 'something extra'.

Lockheed Hydraulic Brakes

A bigger car, the 13-30 hp with 1873cc engine, was produced in 1924, and had the distinction of being the first British car with Lockheed hydraulic brakes as standard equipment. These external contracting-band brakes operated on all four wheels - another unusual feature. Two years later a yet bigger Triumph joined the range - the four-cylinder 2169cc Fifteen, with a very square and upright saloon body. While these first three Triumph models were sound enough, and the design team had proved its willingness to innovate, Bettmann really sought to build 'the big car in perfect miniature', and it was the Super Seven of 1927 that really made the firm's name.

The Triumph Super Seven

It had an 832 cc side-valve engine with three-bearing crankshaft, three- speed gearbox, semi-elliptic front and quarter-elliptic rear springs, and Lockheed four-wheel brakes. Cruising speed was 50 mph. Wheelbase was only 81 inches and with a cost of £150 it replaced the 10/20 model. The Super Seven, produced at a rate of 75 a week by about 800 workers, so dominated Triumph's programme that the Fifteen was displaced. The Seven took over the firm's Priory Street, Coventry, works and the Fifteen production went to Stoke, which had previously produced bodies only.

Donald Healey and the Land's End Trial

Most motoring journals of the era felt the the little 832cc Triumph could never be compared to its bigger rivals, but the three-bearing crankshaft, Lockheed brakes and tough construction soon made the doubters change their tune, and the Super Seven made its mark in trials, hill-climbs and even at

Brooklands races. In the 1928 Land's End Trial, Donald Healey won a silver medal in a Super Seven - the start of a long and successful association between Healey and Triumph. In the same year Gordon England (who was also responsible for one of the many variants offered by outside firms on the Super Seven's ladder chassis) entered the Seven in a 40-Iap JCC High Speed Trial, which included the notorious Test Hill, and won a Gold Medal.

The following year saw more successes - Victor Horsman won the 46th Long Handicap on the

Brooklands outer circuit at the BARC Easter meeting, with an average speed of 78.25 mph. His Super Seven had a special single-seater body with a cowled radiator and tapered tail and head fairing. He won again at the Healey's next outstanding outing in a Triumph was in the 1929 Monte Carlo Rally. He made Monte five minutes after the control had closed, having driven from Berlin: The following year, immediately after finishing fourth in the Riga Rally, Healey set off for Monte from Tallinn, got three hours sleep in the course of the 2160-mile run, and finished seventh overall with the best British performance. The Triumph penchant for out-of-the-ordinary cars was now well established.

1928 Triumph 15, powered by a four-cylinder side-valve 2170cc engine. The Triumph 15 was manufactured from 1927 to 1930.

1928 Triumph 15, powered by a four-cylinder side-valve 2170cc engine. The Triumph 15 was manufactured from 1927 to 1930.

1928 Triumph Super Seven - the car that ensured Triumph's success, for a time. It was powered by a 747cc side-valve engine.

1928 Triumph Super Seven - the car that ensured Triumph's success, for a time. It was powered by a 747cc side-valve engine.

1935 Triumph Southern Cross Sports.

1935 Triumph Southern Cross Sports.

1935 Triumph Gloria saloon, which could be optioned with either a four or six cylinder engine.

1935 Triumph Gloria saloon, which could be optioned with either a four or six cylinder engine.

1939 Triumph Dolomite Roadster.

1939 Triumph Dolomite Roadster.

1945 Triumph 1800 Roadster.

1945 Triumph 1800 Roadster.

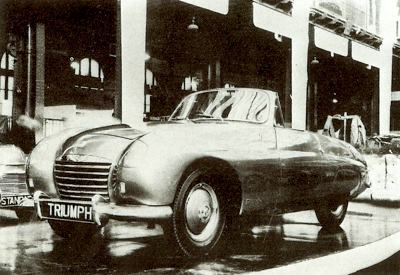

1950 Triumph Silver Bullet TRX prototype.

1950 Triumph Silver Bullet TRX prototype.

1950 Triumph Mayflower, which was powered by a four-cylinder 1247cc side valve engine.

1950 Triumph Mayflower, which was powered by a four-cylinder 1247cc side valve engine.

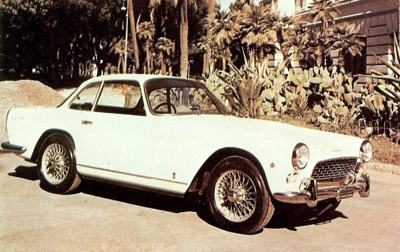

Michelotti designed Triumph prototype, circa 1955.

Michelotti designed Triumph prototype, circa 1955.

1955 Triumph TR3, capable of 105 miles per hour from its 100 bhp.

1955 Triumph TR3, capable of 105 miles per hour from its 100 bhp.

1962 Triumph TR4. Built from 1961 to 1965, it was updated to TR4A specification when it acquired independent rear suspension and four extra bhp to add to the 100 already on offer.

1962 Triumph TR4. Built from 1961 to 1965, it was updated to TR4A specification when it acquired independent rear suspension and four extra bhp to add to the 100 already on offer.

1967 Triumph 1300TC. This bodystyle was first introduced on the 1300 model of 1965 and was later used on the 1500 and Toledo models. The 1300TC was powered by a four-cylinder twin carburetor 1296cc engine developing 75 bhp @ 6000 rpm.

1967 Triumph 1300TC. This bodystyle was first introduced on the 1300 model of 1965 and was later used on the 1500 and Toledo models. The 1300TC was powered by a four-cylinder twin carburetor 1296cc engine developing 75 bhp @ 6000 rpm.

The 2.5 PI MkII used a slightly detuned version of the TR5/TR6 engine, developing 132 bhp instead of 152 bhp. The Triumph 2.5 PI was available in sedan and wagon versions, and remained in production until 1975 when it was replaced by a carburetored version, the 2500S. Unfortunately, by 1975 Triumph had given up using fuel injection altogether.

The 2.5 PI MkII used a slightly detuned version of the TR5/TR6 engine, developing 132 bhp instead of 152 bhp. The Triumph 2.5 PI was available in sedan and wagon versions, and remained in production until 1975 when it was replaced by a carburetored version, the 2500S. Unfortunately, by 1975 Triumph had given up using fuel injection altogether.

|

The Supercharged Seven

A supercharged Seven was introduced as a standard model in 1929, with a Cozette blower mounted on the left of the engine, which was claimed to develop 32 bhp at 4500 rpm and give a 65 mph maximum speed-all for £250. By 1930 a quarter of all Triumph production was being exported and Super Sevens were figuring largely in Australian city-to-city record runs and in Australian and South African trials. A Gnat sports two-seater version was introduced in 1930, and Triumph chased the success of the rival

Wolseley six-cylinder Hornet with a small six of their own, the 1202cc Scorpion, which installed its 56.5 x 80mm side-valve unit in a lengthened Super Seven chassis.

The Triumph Super Nine

The Super Nine was introduced in 1932 with a Coventry Climax four-cylinder 1018cc 32 bhp engine with overhead inlet and side exhaust valves. This engine also went into a new Triumph sports model, the Southern Cross, named in recognition of the firm's Australian sales and competition successes. There was a notable European success for this engine - the first of a number of Coventry Climax units in Triumph cars - when Mrs Margaret Vaughan took the Ladies' Cup in the 1932 Monte Carlo event driving a Nine with a Royston drophead coupe body. She won her prize in spite of stopping to help a crashed crew and setting four broken legs.

Donald Healey joined the company as chief experimental engineer in 1933, with a strong sporting approach to his job. After a new range of Triumphs was introduced in 1934 - the Gloria, supposedly named after a famous London mannequin of the day, and offered in 1087cc four-cylinder and 1476cc six-cylinder form - Healey put seven of them into the Monte Carlo Rally of that year. All finished, and Healey himself took third overall place and won the 1500 Class prize. In the Alpine Rally of the following year the three works Gloria cars took the manufacturers' team prize in the 1100cc class and two drivers - Healey and Maurice Newnham (who was later to become managing director) - received awards for having incurred no penalty points at all.

The Triumph Supercharged Straight-Eight Dolomite

A Gloria Speed Model soon followed, with a triple-carburetor engine and open four-seater bodywork, and 1934 saw the introduction of yet another sporting Triumph, a two-liter supercharged straight-eight Dolomite with body style and engine design 'borrowed' from Alfa Romeo. The production programme stumbled at this point, and the Dolomite was dropped after only three prototypes had been built; though the irrepressible Healey took one on the Monte Carlo Rally of 1935 - and was lucky to escape uninjured when the car was demolished by a train on a level crossing. His competitions manager, J. C. Ridley, managed to avoid trains and finished second overall in another car, taking the 1500cc class award.

In the following year Healey took another Dolomite to eighth place in the Monte. Miss Joan Richmond, in another Triumph, was second in the 1500cc class. All these successes in southern Europe led to the renaming of the Gloria Speed Model as the Monte Carlo Tourer - while in 1935 the special-equipment version of the same car was called the Vitesse. Inevitably, Healey took a Vitesse rallying, and won a Glacier Award in the 1936 Alpine event for incurring no penalty points in an outstanding performance, in his 14/60 saloon against sports cars. Another Triumph driver in this event, finishing fifteenth in a Southern Cross two-seater, was Tony Rolt.

Further competition entries were curtailed by financial problems, though regular class wins were registered in British, Scottish and Welsh rallies for several years. Triumph concentrated on production cars with the development of the Gloria range until 1937, when the Dolomite name was revived for a new range powered by Triumph's own overhead-valve engines-a four-cylinder 75 x 100 mm unit with a 1767cc capacity in the Dolomite 14/60 and Roadster coupe, and a six-cylinder 1991cc engine with 65 x 100mm pots in the Dolomite Two-liter. Bodies were of steel sheet over wooden frames, there being insufficient capital to go over to steel pressings, and though the Dolomites sold well and had a good reputation in the market, the motor industry went into the immediate pre-war doldrums, and Triumph failed.

Thomas W. Ward

There were brief efforts to merge with

Riley, also in deep trouble, and Riley and Triumph both found themselves in the hands of the receiver. Both were saved - Riley was bought by Lord Nuffield as an addition to his Morris, MG and Wolseley string, and Triumph was purchased by the Sheffield steel firm, Thomas W. Ward. War broke out soon afterwards, and any plans Ward had for getting into car production were scotched. The old Coventry works were all but flattened in one of the heavy blitzes to which that city was subjected, and most of the old Triumph records were totally destroyed. Nonetheless the firm was active in aircraft production and built more than a thousand Mosquito aircraft.

It was the plywood construction of this light and fast Pathfinder aircraft that shaped Triumph's immediate post-war car production, after Sir John Black of the

Standard Motor Co. bought Triumph from Ward in 1944, it was one of the first British car makers to resume production with new models. There was the 1800 Renown, whose razor-edge body styling was a direct legacy of the wartime handling of plywood panels, and at the same time the firm also returned to conspicuously rounded contours with the 1800 Roadster, whose bulbous aluminum front wings and long bonnet attracted eager crowds wherever it appeared during those post-war years.

The Triumph Renown

Though the Renown served Triumph conspicuously well until 1955 in the medium-large saloon category, and was particularly liked by professional men, it was the Roadster that most reflected the post-war public need for some racy expression of the old pleasures and the new freedoms. The Roadster was not particularly speedy - its 1.8 OHV long-stroke engine produced only 65 bhp and 75 mph - but it had highly individual looks, boasted an American-style three-at-a-pinch bench seat, two extra dickey-type seats behind the hood with their own pop-up screen, a very solid tubular chassis, transverse springs in front and semi-elliptics at the rear, good road stability, fair all-round visibility, an easily-handled hood, wind-up windows and a full complement of switches.

Only its column-mounted gear change (which admittedly made life easier for the centre of three front occupants) was difficult for the British driver to take. This Roadster, and latterly the Renown, acquired the ubiquitous Standard Vanguard 2.2-liter engine in 1949, a much squarer overhead-valve unit which produced another five bhp and gave the Roadster an extra 10 mph or so - not a lot in today's terms, but a real boost at the time, when every motorist wanted something just a little bit faster. And no one even dreamed of blanket speed limits. Some 2000 Roadsters were built in all.

The Triumph Mayflower

While the Renown sustained Triumph's reputation for solid-quality motoring, the firm also sought to produce quality in miniature, in the way originally outlined by the founder Siegfried Bettmann, who had handed over the managing directorship in 1933, dabbled in Triumph cycles through the late 1930s and retired properly in 1939. Bettmann died, an honoured Coventrarian, in 1951, at the age of 87. The car that tried to reproduce this small-style luxury was the Mayflower, with an aluminum body by Mulliner, and repeating the razor-edge approach (at least one example was produced using Mosquito-style plywood, in fact). aluminum was favoured, not for lightness but because of the post-war steel shortage.

The Mayflower had a conventional 1247cc engine of 63 x 100 mm cylinders, gave a modest 38 bhp and was just as modestly priced at UK£395. Its heavy-looking body, which contained a surprising amount of space despite a mere 84-inch wheelbase, gained a lot of admirers and also a lot of detractors, but Triumph managed to make and sell around 32,000, including 500 convertible models, It did not sell to enthusiasts - it took 26 seconds to labour up to 60 mph from rest - a marked contrast to the things Triumph had in mind.

The Triumph 'Silver Bullet' TRX

At the 1950 London Motor Show a new Roadster was revealed. Its aerodynamic light-alloy body with concealed headlamps earned it the nickname of Silver Bullet, though officially it was the TRX. It abounded in electrical and hydraulic gadgetry-the seat adjustment was hydraulic, the windows and soft top were electric, the headlamps were behind electrically-operated panels, and the bonnet was opened and closed by means of an electrically powered hydraulic ram. The problems presented by this exciting but complicated arrangement started with an embarrassing incident in front of Princess Margaret at the Motor Show. No one had told the demonstrator, the new Triumph Chairman, Sir John Black that the various functions of the control switches had been switched around on the prototype. An electric fire broke out urider the bonnet of the car, one of only three built, shorting all the wiring, and depriving the driver of any means of raising the bonnet. Sir John was forced to stand by and watch the car burn out more or less completely. The penalties of over sophistication were obvious to all. Material shortages because of the Korean war sealed the car's fate.

At this time Triumph decided to go for the US sports-car market and decided on an entirely new model. It was put together in time for the 1952 London Motor Show, and was called the TR1. The car was basically 'pinched' from Triumph's associated company,

Standard, resting on a Standard 8 chassis frame with a Standard Vanguard engine and a bob-tailed body. It was an immediate disaster-it failed to produce any power and handled badly, and BRM's Ken Richardson was hastily called in to sort it out. This he did within three months, replacing the Standard 8 frame with a stiffer chassis, widening the body by two inches, drawing the rounded tail out into a shape that allowed some boot-space, and experimenting with the engine, steering, brake and damper settings. The result was the famous TR2, which quickly made a 115 mph run at Jabbeke in road trim and 125 mph in high-speed trim. Its engine would take any degree of hammering, and it sold for £555 - outstanding value even in those days.

The Triumph TR2 and TR3

While the TR2 was gaining in popularity among young sports-car enthusiasts - this was the period when every young man aspired to owning a drophead sports car - the firm was getting back into the its pre-war competition stride. In 1954 the RAC Rally went outright to Johnny Wallwork in a TR2 - its first competitive appearance. Mary Walker won the Ladies' Prize in another TR2. Richardson himself took another TR2 on the

Mille Miglia and finished 28th out of 365 starters by 'just motoring beautifully the whole way, using only a quart of oil'. The TRs, moving into TR3 and 3A versions through the 1950s, continued to win. In one Alpine Rally, six TRs entered and all finished, taking the team prize and five Alpine Cups, the sixth failing to gain a cup when a wheel came loose.

TR ruggedness and reliability became a by-word. The engine went into several pretty low-volume sports GT cars of the period - Swallow Doretti, Peerless and Warwick. In Italy Michelotti designed a GT fixed-head coupe which Vignale produced in small numbers; called the Italia, it was based on the TR3 chassis and running gear. In 1959 the TR was used as the basis for a Le Mans car, the TRS, with 'five-decker-sandwich' engine -sump, crankcase extension, crankcase, cylinder block and head each stacked on top of the other - of 1985cc (90 x 78 mm) with 9.25 to 1 compression, and producing 150 bhp. Bulging cam covers on top earned the engine the nickname Sabrina (after a well endowed showgirl of the day) among Triumph personnel.

Three of these cars, with stock TR3 body to catch the imagination (and wallets) of the buying public (Triumph research showed them to be mainly in their late-forties and seeking to re-capture their lost youth) competed at Le Mans, but all retired through mechanical failure. The following year they were back with new glassfibre Michelotti bodies. This time they took second, fourth and fifth class positions, one of the cars being timed at 129 mph down the Mulsanne Straight, and averaging 103.8 mph. Finally, in 1961, all the kinks were ironed out and the TRS took the team prize, the first one home making ninth overall, and ahead of all other British entries.

The Triumph Herald

Triumph toyed for a while with the notion of introducing a production TRS as a top-of-range addition to the TR4, which replaced the TR3 in 1961. Some tooling was ordered, but in the uncertainty of the period just before

Leyland took the firm over in December 1960, the car, code-named Zoom, was dropped. Meanwhile Triumph had not been idle on the saloon front. Anything but - 1959 saw the introduction of the Herald. Designed by Michelotti, it had a traditional chassis and seven-section body designed for quick and cheap replacement in the event of damage. Insurance companies loved it. Suspension was independent all round-wishbones at the front, swing-axles at the rear-the turning circle of 24 feet rivalled that of the London taxi, and engine access was total, the whole bonnet and front wing section swinging upwards and forwards (a ploy which Peerless and Warwick had used).

The 948 cc unit produced 38.5 bhp in the saloon version, and 50.5 bhp in the coupe and convertible versions. The Herald went into 1200 and stripped-down S versions in 1961, 12/50 version with 1147cc engine and the first standard sunshine roof in its class in 1963, and then to 13/60 with a 1296cc unit in 1967. By the time the Herald was replaced by the Toledo in 1970, something like half a million Heralds in all versions had been built. Impressed as the world had been with the 948cc Herald in 1959, it was not generally known that at the time Triumph had been aiming for a very simple small car designed to give 60 mph and 60 mpg -the '60/60' car would become one of the catch-phrase ambitions of the post-energy crisis - to compete directly with the VW Beetle which was then making its presence felt in many markets.

The Triumph Zebu

There was another prototype too - the Zebu, a six-cylinder car of two liters with transaxle, MacPherson strut front and trailing-link rear suspension. The transaxle was abandoned in favour of a normal front gearbox because of torsional problems, and two body styles were toyed with, one of them very close to the cut back rear window which Ford adopted on the Anglia. The Zebu foundered when Triumph hit its pre-Leyland-takeover cash shortages in 1960. But the mechanical experience was not wasted ... it proved useful in developing a new six-cylinder car that did make it - the 1.6-liter four-headlamp Vitesse version of the Herald, launched in 1962.

The Triumph Spitfire

Other Zebu lessons, especially about suspension, were applied to a new larger saloon, the 2000 of 1963. The 2000 used the Standard Vanguard six-cylinder engine in a completely new unitary body, with independent suspension all round and a good standard of equipment and comfort. Meanwhile the TR sports-car series was backed up by a second string. As the TR moved into squarer Michelotti-designed 4 series in 1961, a two-seater based on the Herald took shape-the Spitfire. This car utilised a lot of Herald components, and inherited the saloon's tiny turning circle and generous luggage space. . Development was reciprocal - the special camshaft of the Spitfire was used when the Herald moved into 12/50 form in 1963.

The Spitfire was progressively refined in the engine compartment and in styling, with a Mk II appearing in 1964, Mk III in 1967 and a Mk IV in 1970. As the Vitesse developed out of the Herald, it was inevitable that Triumph engineers should seek to do the same six-cylinder exercise with the Spitfire. The result was the GT6 of 1966 - the same year that the Vitesse was uprated to two-liters. GT6 improvements paralleled those of the Spitfire. Both Spitfire and GT6 proved enduringly appealing; the Spitfire outlasted the larger GT6, and it continued to sell well in its 1493cc form here in the the USA, where success has been decisive to continuing British sports-car manufacture.

Harris Mann's TR7

Local US buyers also took large quantities of the later developments in the TR series - the TR5 of 1967, which employed the fuel-injection six-cylinder 2500 engine that also found its way into the 2000 saloon to create the top Triumph, the 2.5 PI of 1968, and the TR6 of 1969. A TR7, with dramatic wedge styling by Harris Mann, was introduced in 1974, to be sold initially in the US market, with TR6 production continuing in parallel until 1976. One of the immediate results of

Leyland's takeover in 1960 had been the reorganisation of the competitions department, this time under Graham Robson, and with a slim budget. TR4s were the department's first weapon, but had a patchy career, being neither fast nor rugged enough; in 1963 Robson added Vitesses to the armoury, and the following year rally Spitfires, Le Mans Spitfires and 2000 saloons. The Spitfires did particularly well.

The Le Mans cars used aluminum bodyshells and glassfibre hardtops modelled on the GT6 which was by then in prototype form. Special nose shapes were designed to cleave the Le Mans airstreams, and power was increased to 98 bhp - though little had to be done to the suspension. These cars amazed everyone by topping 130 mph down the straight and lapping Le Mans at 100 mph. In the race, two crashed and one finished, averaging 95 mph. By the time Robson left in 1965 the rally version of the 2000 introduced in 1963 was shaping well, and with Finn Simo Lampinen signed up among the up-and-coming drivers they were ready for some outright wins. But rallying was getting into its big-time swing, with drivers paid on a new scale and full service back-up costing the earth and being all but necessary if a team wanted to earn top placings.

Leyland was not prepared to put the money in, and the Triumph challenge thereafter became sporadic. The firm's World Cup Rally challenge was with 2.5S based largely on the work done in the mid 1960s. It was the Dolomite Sprint and TR7 that managed to uphold Triumph's sporting name. The TR7 rally car at last became successful following the long-awaited transplant of Leyland's famous 3.5-liter V8 engine in early 1978. The Dolomite Sprint was one of a line of cars stemming from the front-wheel drive 1300 model of 1965, a medium sized sedan which yet again re-echoed the old Bettmann tenet of producing large-car quality in scaled-down form.

The Triumph Toledo

In 1970 a revised but similarly styled bodyshell was introduced with a new engine range. The 1300 became the Toledo, with rear-wheel drive-it replaced the last ofthe Heralds-and there was a front-wheel drive 1500 . and a 1750 slant-four rear-wheel drive Dolomite whose engine had been sold to Saab since 1967 for use in their 99 model. The difference in layout within this range was finally resolved when the 1500 was given rear-wheel drive. The engine was also uprated with twin carburetors. The Dolomite engine as used in the four-door car was of 1854cc and in 1973 the Sprint was introduced with a 16-valve four-cylinder 1998cc engine with single camshaft lying between the valve rows.

The Sprint, while proving its mettle on the circuits, was also widely regarded as one of the most exciting but civilised road cars produced in Britain in the mid 1970s. Triumph always leaned towards the sporting side of motoring, and while the robust but comparatively unexciting 2000 was sustaining Triumph's name in the executive market, plans were afoot for a coupe version. A 2000 was sent to Giovanni Michelotti, whose affiliation with Triumph went back to the original Herald and to the switch from the rounded contours of the early TRs to the squarer TR4. Michelotti's brief was to produce a car to stimulate interest at the Geneva Motor Show, but what he styled on a shortened 2000 saloon floorpan so excited Triumph executives that they bypassed the show plans and had the car whisked straight to Coventry for their production experts to look at.

The Triumph Stag

At that stage it was powered by the 2000'S straight-six engine. But Triumph were already toying with the other half of the Dolomite slant-four engine - in other words, a V8 was being knitted together - and it was obvious that this unit should go in the proposed coupe. In enlarged 3-liter form it did, and with uprated 2000 components to cope with the extra power, the new car was launched in 1970 as the Stag. The Stag, aimed substantially at the US market but never to take off in the sort of quantity which those initially enthusiastic executives dreamed of, did introduce a new approach to the roll-over bar. The first design, incorporated as part of the general concern for safety standards (particularly here in the USA), was of the conventional race-type - a fairly simple hoop situated amidships.

Such were the doubts at Triumph over it that it was a bolt-on affair which the owner might remove if he wished. But torsional problems developed in the body, and since it was felt that the motoring public at the proposed Stag level had outgrown the scuttle-shake which for years had been a feature of open cars, the hoop roll-over bar was endowed with a leg that fixed to the centre of the top of the windscreen. The roll-over bar thus became a roll-ever cage - the first of its type to be marketed by a car maker. And it proved in effect that the roof could be sliced off a saloon and replaced by a three-legged cage.

The Ryder Report

The Stag suffered from the unreliability of its V8 engine which was prone to overheating problems, and the car acquired the reputation of being expensive to maintain, particularly when replacement cylinder heads were required. Indeed some people went to the lengths of replacing the Triumph V8 engine with its Rover counterpart. In 1977 the Stag was dropped, and for 1978 the Triumph range consisted of the Dolomites, including the Sprint, the Spitfire and TR7. Management acrobatics at British Leyland made Triumph part of the Specialist Car Division and then of Rover-Triumph. The latter structure had a great deal of finance pumped into it before the re-formation of British Leyland under the terms of the Ryder Report called for the Government to assess on what terms the Corporation should have public money.

1978 saw yet another reorganisation of British Leyland, this time-under new chairman Michael Edwardes, and Triumph became part of the specialist division of Rover-Jaguar-Triumph separate from the high-volume Austin-Morris division with a brief to concentrate on sports car production, although a successor to the Spitfire or variations on the TR7 were thought unlikely to appear very quickly given the constraints on investment during the late 1970s.

From 1978 BMC started rallying a Rover 3528cc V8 engined version of the car, naturally enough called the “TR7 V8”, however the true TR8 production car was only ever sold in the US in 1980 - 1981. In 1979 a convertible joined the existing TR7 coupe, while other versions included a 16-valve 'Sprint' derivative. But in 1977 a protracted strike by the Liverpool factory workers would all but kill off the car. The management switched production to Coventry, and then finally to the Rover plant at Solihull, but the car was always dogged by controversy, a poor quality reputation, and finally by adverse currency movements between the British pound and the US dollar. Production ended in October 1981, after 86,784 TR7 coupes, 24,864 TR7 drop-heads and a mere 2,815 TR8s had been built.

Also see: Triumph Car Reviews |

Lost Marques - Triumph (AUS Edition)