The Slogan of the Riley company was '

As old as the industry-as modern as the hour'. And for the first 40 years of the company's history it was an accurate boast, even if the latter years of Riley were to demonstrate that the sort of enterprise which flourishes freely in a family business has no place in a giant industrial group.

Long before the motor age, the Riley family was prominent in the Coventry (UK) weaving trade; but the weaving trade was dependent on work being carried out at very cheap rates by child labour in the villages round Coventry. When the children were sent to school by the various British education acts of 1870-80, the situation changed drastically and the then head of the company, William Riley Jr saw the beginning of the decline of the weaving trade.

He began casting about for another outlet into which Riley could profitably diversify, and which would ensure security for his sons Victor, Stanley, Allan and Percy. In 1 890,William Riley bought up an established cycle manufacturing company, Bonnick & Co, based in King Street, Coventry, convinced of the sound future for the cycle industry.

Manufacture was carried on under the Bonnick name for several years, then, in May 1896, the corporate name was changed to the Riley Cycle Company Limited. About this time, the first stirrings of the motor industry were making themselves apparent in Coventry, and the imagination of the Riley boys was fired by the appearance of a Bollee tricar on the streets of the city. This was almost certainly the vehicle which inspired Harry J. Lawson to pay £20,000 for the British rights to the Bollee patents.

The young Rileys decided to build a motor car, the design and construction of which were carried out by Percy Riley, who had just left grammar school. Work on the little voiturette started in 1896, and it was completed in 1898, having been entirely constructed in the factory of the Riley Cycle Company; Percy Riley even cut the gearwheels by hand. The result was a neat little four-wheeler on Vivinus lines, with a front-mounted vertical single-cylinder air-cooled engine with a mechanically operated inlet valve.

This was one of the very earliest instances of a positively opened and closed inlet valve, but though the little car proved a success, the design was not put into production, and after a few years of use around Coventry, the voiturette was sold to a Belfast motorist. When the Riley company did go into motor vehicle production, it was with a far less adventurous machine, the Royal Riley, which was an almost exact copy of the De Dion motor tricycle, with a single-cylinder engine mounted behind, and geared directly to the rear axle.

A quadricycle version, with two front wheels and a forecarriage seat for a passenger, was also available. This type of machine, with its obvious pedal cycle ancestry, was already becoming dated when Riley entered the field, but it seems that old William Riley was not prepared to commit himself any further to the motor vehicle until it had proved something more than a temporary wonder. And thus these first production Rileys used proprietary engines of De Dion type rather than employing Percy Riley's proven talents as an engine designer and constructor. That would have involved the company in the expense and inconvenience of installing engine production machinery. It was simpler to buy in a reliable. product.

The Riley Engine Company

But the situation did not please the younger Rileys, who were itching to build motor car engines. In his spare time, Percy had developed a new 8 hp water-cooled power unit - with a mechanically operated inlet valve - which proved so successful that he and brothers Victor and Allen, had decided to start a separate company to produce the engines. Accordingly they founded the Riley Engine Company, in 1903, aided by cash loaned by their parents. By 1904 their power units were standardised on the Riley motor cycles and tricycles. Three-wheelers increasingly took the attention of the Riley company. Their great advantage was that a passenger could be carried, and by 1905 the Riley Tricar had been transformed from a spidery machine with handlebars and other obvious cycle features into a wheel-steered machine of eccentric appearance with obvious pretensions to light car status.

Though the tricar enjoyed a certain amount of competition success, its freakish appearance emphasised that this was an evolutionary 'sport' which would soon become extinct. Development began on a four-wheeler which preserved the best features of the tricar, such as its constant-mesh transmission (another Percy Riley development) and its 1034 cc V-twin engine, within a more orthodox styling context. In fact, the new Riley, which made its debut in 1905, looked something like a baby Lanchester, with a snub-nosed radiator set well behind the front axle, and a leather apron to keep some of the weather off the occupants. The engine was mounted under the seats, though this was done in the interests of simple construction rather than with any ideas of ameliorating weight distribution or handling.

1909 2-seater Riley Runabout, which was powered by a twin-cylinder 2 liter engine.

1909 2-seater Riley Runabout, which was powered by a twin-cylinder 2 liter engine.

1923 Riley Redwinger. It was powered by a four-cylinder 1500cc engine.

1923 Riley Redwinger. It was powered by a four-cylinder 1500cc engine.

The Book of the Riley Nine.

The Book of the Riley Nine.

1929 Riley Nine, which was fitted with a 1087cc four-cylinder engine.

1929 Riley Nine, which was fitted with a 1087cc four-cylinder engine.

1938 Riley 16hp Big Four Kestrel sedan. It was powered by a 1496cc four-cylinder engine.

1938 Riley 16hp Big Four Kestrel sedan. It was powered by a 1496cc four-cylinder engine.

1946 Riley Two point Six model, which was manufactured until 1953. It was powered by a 2.5 liter four-cylinder engine.

1946 Riley Two point Six model, which was manufactured until 1953. It was powered by a 2.5 liter four-cylinder engine.

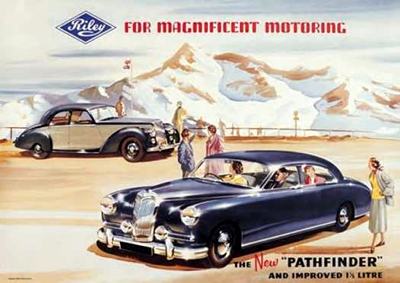

Produced between 1953 and 1957, the Riley Pathfinder was very popular and even found its way into use with the British police force.

Produced between 1953 and 1957, the Riley Pathfinder was very popular and even found its way into use with the British police force.

The Pathfinder was fitted with a 2443cc four cylinder engine developing 110 bhp @ 4400 rpm.

The Pathfinder was fitted with a 2443cc four cylinder engine developing 110 bhp @ 4400 rpm.

1962 Riley 1.5. It was powered by a 1489cc four-cylinder engine which developed 68 bhp @ 4500 rpm.

1962 Riley 1.5. It was powered by a 1489cc four-cylinder engine which developed 68 bhp @ 4500 rpm.

Riley One-Point-Five.

Riley One-Point-Five.

Riley One-Point-Five.

Riley One-Point-Five.

The Riley Elf Mk 3 Sedan of 1966 was based on the BMC Mini, and powered by a 998cc engine.

The Riley Elf Mk 3 Sedan of 1966 was based on the BMC Mini, and powered by a 998cc engine. |

Old Midnight

Another important development pioneered on this little car was the centre-lock detachable wire wheel, which became standard equipment from a very early date; a profitable business was done with other car manufacturers who adopted this system. A couple of years after the introduction of the 9 hp car, a more powerful front-engined version appeared, rated at 12/18 hp. So much overtime was involved in the development of the 12/18 that the prototype was given the nickname Old Midnight. Its 2076 cc power unit was powerful enough to permit the fitting of five-seater coachwork, though a two-seater body continued to be available.

By 1908 the old tricars had been discontinued, and production was concentrated on the 9 hp and 12/18 hp cars; the latter proved so successful in sales and competition, that a smaller version, the 1390 cc 10 hp was announced for 1909. Though the credit for the design was given to Stanley Riley, the specification followed Percy's 12/18 very closely. Stanley's talents, it seems, were more those of the stylist, for he soon created a splendid low-slung semi-racing Speed Model 10 hp which was just the thing for the young bloods of the day, with its sporting appearance, manly discomfort and low price; nor was the sporting aspect of the Speed Model purely visual, for the 10 hp carried off quite a few sporting events during its natal season.

Meanwhile, Percy Riley was making fruitless experiments with a double-sleeve-valve engine design, the only positive result of which was the first in-line four-cylinder Riley power unit ... but from 1910-13 there was no change from the proven 10 hp and 12/18 hp models (the stubby 9 hp was phased out during 1910), which were fitted with some of the more handsome light car bodywork of the period, the four-seater Torpedo being especially elegant. It seems, though, that the Riley Cycle Company was making more money from the sale of their detachable wheel system than from complete vehicles, and at around 1912, old William Riley decided to stop making cars altogether.

The Riley Motor Manufacturing Company

The move obviously displeased the younger members of the family, who set up a new company, the Riley Motor Manufacturing Company, to take over the car manufacturing interests (and further confuse the already complicated corporate relatjonship of the Riley family companies). So, as the Riley Cycle Company had stopped building bicycles the year before, it not surprisingly changed its name to Riley (Coventry) Limited. Profitable though the wheel business may have been, it was also fraught with legal pitfalls, as several similar types of splined-hub detachable wheel systems had been independently conceived and patented.

The various patentees, notably Riley and John V. Pugh of Rudge-Whitworth, were soon engaged in the costly to-and-fro of claim and counterclaim, shuttle-cocking through the courts until the dispute was decided by the House of Lords in favour of it iley. The introduction of cheap detachable steel artillery wheels was soon to undermine the position of centre-lock wire wheels for any but the more specialised forms of motor car, and settle the argument far more effectively than any court of law.

The Riley Motor Manufacturing Company was quick off the mark with a new model, which appeared at the 1913 Olympia Motor Show. This was the 17 hp, the firm's first production four-cylinder model, which had a monobloc 2951 cc side-valve engine. It was a far more substantial machine than any previous Riley car and was again the work of Percy Riley. Early models had a three-speed gearbox of conventional design that was later replaced by a four-speed unit with constant-mesh third and top engaged by dog-clutches. The refinement of the design was typified by the adoption of Lanchester worm-gearing for the final drive.

The Nero Engine Company

Now another Riley family company entered the field of car manufacture. This was the Nero Engine Company, founded by Victor Riley and headed by Stanley Riley, newly returned from a world tour. The Nero company proposed to build a 1097 cc 10 hp model of similar concept to the 17 hp, but with the engineering details somewhat simplified to bring down production costs. But only a trio of prototypes had been completed before war broke out in August 1914, and all the Riley companies turned to munition production 'for the duration'. During the war, the Nero Engine Company laid the foundation for the post-armistice expansion of the Riley car manufacturing interests by acquiring land at Foleshill, near Coventry (UK), for a munitions factory.

This became the main Riley car factory in 1919, after Riley (Coventry, UK) ceased detachable wheel manufacture and amalgamated with Nero Engine Company, moving into the Foleshill factory. Meanwhile the Riley Motor Manufacturing Company had opted out of chassis manufacture and changed its name to the Midland Motor Body Company, and the Riley Engine Company was assembling the pre-war 17/30 hp model from its stockpile of 1914 parts. The latter venture lasted until the introduction of the horsepower tax in 1921, by which time the components store must inevitably have been pretty empty, and then the company changed over to the production of Percy Riley-designed stationary lighting engines and marine power units.

Harry Rush's 11 hp Riley

It is likely this change in production was over-shadowed by the announcement of an entirely new car from Riley (Coventry) Limited just before the 1919 Motor Show. The first Riley not designed by one of the Riley family, the designer of the new 11 hp Riley was Harry Rush. He had created a car to meet the demands of the times for an easily maintained owner-driver vehicle. All unnecessary greasing was eliminated by the adoption of self-lubricating bearings for items such as brake and clutch control shafts, and the chassis had only six greasing points, which required attention twice a year. 'It is,' eulogised the Daily Graphic, 'a real thoroughbred', and among the finer points of its breeding was a four-speed gearbox, a most useful fitting at a time when nearly all light cars only had three forward gears, even though it was liable to be temperamental.

The

Runabout motoring journal criticised the Riley for having its throttle pedal on the right, as most cars of the day used a centre accelerator, and for having the oil filler and dipstick on the opposite side of the bonnet to the petrol filler. These were minor points, and the failure of the gearbox was excusable in a car which had been badly treated, so Runabout finished on a reasonably complementary note. 'The firm evidently possess a power unit of unsuspected efficiency, their fast hill-climbing being an eye opener to most of us. I understand that the 'pass-out' standard for these engines is now 35 bhp at 3200 rpm, and I can well believe it, for even the works hack was a rare goer. Moreover, they are not rough after the manner of some "hotted" engines but their milder running is as lady-like as their stunt work is ferocious, and they are devoid of any perceptible period.'

The Midland Motor Body Company and the Redwinger

Among the more curious aspects of the Riley Eleven was the use of laminated steel disc wheels, in which the number of laminations was increased according to the weight of the body, so that the heavy all-weather and saloon models had wheels with concentric circles of rivets locating the laminations. Bodies were made by the Midland Motor Body Company, and were notable for their weather protection: notable, that is, except for the two-seater Sports Model; introduced in 1922, which had only a half-height folding windscreen and no hood. A more practicable sporting model was launched in both two and four-seater form for the 1923 season - this was the immortal Redwinger, so-called because the wings and chassis were painted bright red, while the body was normally finished in polished aluminum.

With an engine tuned to give 42 bhp, the Redwinger was capable of 70 mph. Wire wheels gave the car a more orthodox appearance and, by the end of 1924, four-wheel brakes were available as an optional extra. For 1925 the engine capacity of the Riley was increased from 1498 cc to 1645 cc, uprating the taxable horsepower to 11.9 (though the old 10.8 hp engine was available as an option). Amazingly, the old Riley Engine Company 17 hp model was still listed in 1923, though whether it could have found any customers at that date is highly unlikely. In any case, that company was preoccupied with its non-motoring activities; but it was not long before the ingenious brain of Percy Riley was once again engaged in engine design.

He and Stanley devised a compact two-main-bearing power unit of 1087 cc which had pushrod overhead valves in hemispherical heads, an unusual and advanced configuration for a light car of the mid-1920s, and one which made the engine an obvious challenger to the 'hot-stuff' continental 1100S. A low roofline was achieved by providing footwells for the rear passengers, while another novel feature was a built-in luggage boot. This model, known as the Monaco, made its debut in the summer of 1926, and caused a great deal of interest; to further confuse the tangled corporate structure of the Riley family companies, this new Riley 'Nine' was initially built by the Riley Engine Company and bodied by Midland Motor Bodies Limited; later on, Riley (Coventry) Limited also took a hand in the production of the chassis.

The Riley Nine

Meanwhile, there had been some interesting developments of the older Riley engine, including an abortive supercharged overhead-valve version of the 10.8 hp model, mounted in a long-wheelbase chassis with underslung rear suspension, while a standard 12 hp tourer had blazed a new road from Nairobi to Mombasa. Yet the car of 1927 was definitely the Nine. Victor Riley, now Managing Director of Riley (Coventry), summed up its achievements in a letter written in January 1928. 'The year just ended has established the Riley Nine high in the favour of discriminating motorists and has justified still further its title of "The Wonder Car".

Apart from this high reputation so made in the hands of motorists on the road, it has also given to Britain preeminence in the 9 hp class both on road and track. Its main successes during 1928 include: the winning of the 1100 cc class in the RAC Tourist Trophy Road Race held in Ulster; the winning of the 1100 cc class in the Essex 6 hours Endurance Race held at Brooklands; the capture of 8 International Records at Brooklands from 5 kilometres at 97.5 mph to 6 hours in which 511 miles were covered a wonderful performance for a non-supercharged engine; the winning of 7 gold medals by private owners in the MCC High Speed Reliability Trials held at Brooklands in which the leading private owner covered 64.5 miles in the hour on a Riley Nine Monaco Saloon. the winning of both the President's and MAC Cups at the Shelsley Walsh Hill Climb.'

Parry Thomas, the 'Welsh Wizard', had also realised the speed potential of the Riley Nine, and was working on a racing conversion of the car at the time of his death while attempting the World Land Speed Record in 1927. The development programme was carried on by his assistant, Reid Railton, on a chassis shortened and . lowered by Thomson & Taylor of Brooklands. The engine was tuned and fitted with twin carburetors and a four-branch exhaust, which modifications produced a power output of 50 bhp. This was the first Brooklands Riley, and the prototype for what was to become a much-acclaimed production sports-racing model.

On its first competitive outing, this car had a runaway victory in the 90 Short Handicap at the Autumn 1927 Brooklands meeting, winning by a clear mile at a speed of 91.37 mph. Obviously attempting to wrest some of the laurels from this 9 hp upstart; Harry Rush designed a Ricardo-type cylinder head for the 11.9 hp sidevalve model, but this increase in power failed to reprieve the model from being phased out entirely during the 1928 season. The Riley Nine was not to remain the sole production model for long, however, as the old four-cylinder was stretched to six cylinders and launched at the 1928 Olympia Show.

The bore and stroke were identical to the smaller model, giving a swept volume of 1631cc, With regard to the body design, too, the Riley Six followed its smaller sister, as it carried an enlarged version of the Monaco fabric saloon coachwork, known as the Stelvio. The Brooklands model had only a moderate season during 1928: high-speed competition work revealed a number of engine faults. When Brooklands Rileys seemed set fair to win the Ulster TT, a series of spectacular crashes eliminated the cars of Maclure, Gallop and Davis, leaving the race to Kay Don's Lea-Francis.

The Riley Nine Mark IV Chassis

A major improvement to the Riley Nine was made in mid-1929 with the introduction of the Mark IV chassis, which featured strengthened side-members, 'more supple but no less stable' springs, larger brake drums (with compensated cable-and-pulley actuation that could be adjusted from the driving seat) and stronger wire wheels. At the same period, the Stelvio was completely redesigned to give a lower roofline and a better-shaped luggage boot; a similarly styled body on the 9 hp chassis was known as the Biarritz. Though most Riley bodies were built by the Midland Motor Body company, there were a few exceptions: in 1928, KC Bodies of Fulham announced a four-seated beetle-backed sports version of the standard nine chassis. Distinguishing points were an extra-long bonnet, wide doors giving access to front and back seats, a spare wheel stowed in the tail (or carried on the running board) and winding windows in the doors.

But such one-off coachwork stood little chance against the curious Riley Nine pricing system, as the Monaco saloon, the fabric tourer, the metal-panelled tourer and the metal-bodied two-seater retailed at UK£298. On the sporting side, the 1929 season brought a minor triumph for the Brooklands Nine: in the Ulster TT, Sammy Davis finished 12th despite rain and a frozen clutch in the non-supercharged car. A new six-cylinder model was brought out in October 1929: this was the Light Six, which used the 1631 cc engine in a Nine chassis lengthened six inches to accommodate the extra two cylinders.

It was not only Riley cars which followed the Monaco's lead: other manufacturers, from Morris to Crossley, aped its lines, not always with success, a fact which Riley were quick to comment on in their advertising: 'Today the highways and the by-ways of the world prove the influence of the "Wonder Car" on general design throughout the Motor Industry. Body lines are following the Riley vogue everywhere, and beneath the bonnet earnest endeavours are being made to ensure a similar standard of performance....'. Performance was indeed one of the Riley's strong points. In October 1929, Eldridge, Railton and Thomson drove a Monaco round Montlhery, setting up a new class 1100 cc record of 65.83 mph over 1000 miles.

Nor was this achievement to prove unbeatable, as on May 28 - June 4 1930 Eldridge and George Eyston circled Montlhery in a Monaco, taking records from 1000 miles (at an average of 67.79 mph) to 5000 km (64.39 mph), the car running for over 48 hours with a sealed bonnet, the only access to the engine being through an external oil filler. It was an encouraging result. A keen Riley Nine owner of the period was Raymond Mays, who had a 1929 Biarritz, which proved remarkably trouble-free: 'I have driven cars of all types and sizes and can honestly say I do not know of a more fascinating car - in fact the more cars one drives the more one realises the merits of the Riley - I fully understand the great enthusiasm of all Riley Nine owners ... may I congratulate you on a really thoroughbred car in which the full meaning of the word "thoroughbred". plays a greater part than in any car I know.'

Mays retained his enthusiasm for the marque, and a couple of years later was racing the 'blown' 12/6 White Riley, which was the genesis of the ERA. The 1930 Motor Show saw the adoption of full Wyemann construction for the Monaco, and a considerably improved chassis, known as the Mark IV Plus, featuring grouped lubrication, rear-mounted fuel tank, stainless steel radiator and brightwork, and minor controls grouped in the centre of the steering wheel. The light Six now became the Alpine - a particularly handsome (and rare) mascot of a girl skier was created for this model - while the larger Stelvio acquired Silentbloc bushes on its springs.

V.E. Leverett's All White Riley Monaco

A novel feature of both six-cylinder models was a mixture strength control with built-in idiot-proofing: if left set at 'rich' a warning was given as soon as the driver tried to use the horn button. An all-white Monaco Special carrying an impressive battery of auxiliary spotlamps was entered in the January 1931 Monte Carlo Rally by V.E. Leverett. Starting from Stavenger in Norway, he covered the first 900 miles over icy roads on snow chains. He managed to extricate his car when it skidded into a ditch, and still to cover the 2261-mile course at the stipulated average of over 22 mph to arrive at Monte Carlo on time, winning the 1100 cc class in spectacular fashion.

Another novel journey was the London-Cape Town trip led by Captain G. Malins, driving two Alpines fitted with special 'safari' coachwork incorporating inflatable flotation gear for crossing rivers; though an attempt to convert a Riley into a paddle-driven vessel proved fruitless. The same month Donald Healey won the 1100 cc class of the Paris-Nice Trial with a Riley Nine tourer, while later in 1931 Dudley Froy drove a Brooklands Riley to victory in the German Grand Prix at the

Nurburgring, averaging 58.03 mph in heavy rain-the car was driven to and from the race under its own power.

The Riley Plus Ultra

An interesting form of construction was essayed on a 1931 Riley by Laminoid Limited of London. The panels of their experimental coachwork was pressed from a form of sheet asbestos, which could be moulded into the most awkward shapes, and which presaged the use of glassfibre for car bodies. At the 1931 Olympia Show, a new dropped chassis frame for the Nine was introduced, and body construction was again improved, earning the new range the generic title of 'Plus Ultra' ; the diamond shape of the Riley radiator badge was echoed in the shape of the side windows and bonnet louvres while a new sporting two-seater, the Gamecock, was added to the range. Then, to round off the year, it was announced that Riley (Coventry) Limited was taking over the Riley Engine Company and the Midland Motor Body Company, thus clearing up an anomalous situation which had been in need of clear resolution for a number of years.

The Riley Nine Falcon, Lincock and March Special

In the spring of 1932, details were released of a new Brooklands model, this time fitted with a 1486 cc version of the six-cylinder engine, though it was a four-cylinder Brooklands, driven by Elsie Wisdom and Joan Richmond, which won that season's Junior Car Club 1000 miles race at Brooklands. The new 12/6 engine became available on touring models for the 1933 season. The Riley line-up at the 1932 Motor Show was truly impressive: there was a new 14 hp luxury Edinburgh saloon, experimentally equipped with the Salerni fluid flywheel transmission, which also had a freewheel built-in behind the gearbox, while the new Nine Falcon was a low-built saloon with hinged roof panels opening with the doors to facilitate entry (hardly surprisingly, few examples of this model were built).

Other new Nines included the Lincock coupe, the Lynx tourer and the March Special sports tourer, while the new-12/6 chassis was available with Kestrel fast-back coachwork. A sloping radiator was adopted for the Monaco. There were sporting triumphs to boast about at the Show, too: on 25-26 October George Eyston and Bert Denley had broken a succession of Class records at Montlhery with a 12/6 Brooklands model, averaging 92.82 mph over 12 hours, 91.68 mph over 2000 km, 82.54mph over 3000 km and 82.31 mph over 24 hours. A couple of days later, Freddie Dixon, who had only started racing that season, set up class records with his Riley Nine at Brooklands. He covered 50 miles at 110.37 mph, 100 miles at 111.09 mph, 1 hour at 110.93 mph and 200 km at 110.67 mph.

"Fiery" Fred Dixon and the Red Mongrel

'Fiery Fred' became renowned as the leading Riley tuner: the car he used to take the records was his celebrated Red Mongrel, which was a narrow single-seater using a chassis with cut-down Arrol-Aster side-members and a highly-modified Riley TT engine with one SU carburetor per cylinder. The carburetors were tuned by running the engine in the dark and adjusting each mixture control until the exhaust flames were identical. Red Mongrel won the 1933 Mannin Beg race in the Isle of Man, while another Riley Nine driven by Peacock/Von der Becke won the 1500 cc class at Le Mans (and was fourth overall).

The Riley MPH

Four new 12/6 racing cars with a wedge-shaped profile appeared in the 1933 Ulster TT, that of Whitecroft winning its class: these TT racers would become one of the handsomest two-seater sports cars of the mid-1930s, the Riley MPH. The MPH had a little sister, the Imp, which appeared in prototype form at the 1933 Olympia Show, but did not achieve its final form until the spring of 1934. With their long bonnets, flared wings and bobbed tails, the MPH and Imp rivalled the top Continental sportsters for elegance. The MPH was launched at the 1934 Motor Show. It had the new 1725 cc 15/6 engine, which was basically the old 14/6 bored out, plus a Wilson preselector gearbox, which was also available as an option on other models (and would later be standardised).

There was also another new power unit, a 1½-liter four planned something after the fashion of the Nine - but this engine wasn't the work of Percy Riley, who had backed out of the project following a disagreement, but had been developed by Hugh Rose. Nevertheless, the 1496 cc 12/4 for a close family resemblance to the Nine. It would be the backbone of the Riley range for the next two decades. In the next year the power unit choice continued to proliferate: a 2178 cc V8 appeared at the 1935 Olympia, compounded of two Nine cylinder blocks on a common crankcase, with Adelphi or Kestrel bodywork.

Autovia Cars

The Monaco was dropped that year, and the Merlin, a new, more streamlined version of the Nine, took over. The Monaco name, if not the styling, was revived for 1937, in which year Riley, reverting to type, set up a new subsidiary company. The new holding, Autovia cars, produced a very few 2849 cc V8 luxury cars designed by Charles Van Eugen, ex-Clyno and Lea-Francis. The abrupt appearance and rapid disappearance of the company was symptomatic of the financial situation of the parent concern. For the seemingly uncontrolled flood of new models and power units - the 2443 cc Big Four appeared in mid 1937 - was sapping the strength of Riley (Coventry), and shortly after the announcement at the end of 1937 that a new 9 hp model, the Victor, with 'the new thrill of Dual-Overdrive' (a five-speed transmission) for only £299, came a grimmer statement.

It was announced that Riley had made a loss for the last trading year, and by February a receiver was appointed, while talks were going on with Triumph about a merger between the two companies: then, in October 1938, Lord Nuffield bought Riley, claiming that he was 'desirous of preserving in every way the development of those characteristics that have made the Riley car so outstanding.' Although the sports Rileys had short shrift under the new regime, the touring models did manage to preserve some measure of individuality, the Big Four and the 12/4 continuing after the merger - and, indeed after the war, when they were graced with handsome coachwork with fabric covered roofs, and acquired torsion bar independent front suspension.

Once the unlikely merger that created the British Motor Corporation had taken place, however, the Riley name was dragged through the corporate mud, and became synonymous with suburbia-orientated badge engineering, where the only difference between a Riley and a Wolseley was the shape of the front grille. It is probably better to draw a discreet veil over the declining years of Riley, which died unmourned as an upmarket version of the Mini and 1100/1300 models, and to remember instead the classic models like the Monaco and the Imp which made the life of Riley such a colourful marque in the annals of motoring history.

Recommended Reading: Riley - As Old As The Industry, As Modern As The Hour |

The History of Riley (AUS Edition)