The Most Successful Car-Maker In Racing

In its day the Sunbeam company was justifiably considered to be motor-racing pioneers - they were world land speed record holders, the first to exceed 200 mph, for 32 years the last British car to win a Grand Prix race, and for 20 years from 1908 to 1929 the most successful car-maker in racing. They were also builders of high-quality road cars sometimes in their day known as the poor man's Rolls-Royce, although this back-handed compliment was also applied to Rover, Talbot and Jaguar at different periods of motoring history.

Alderman John Marston, J.P.

The Sunbeam company sprang from cycle-making, as did many of the early British motor-makers. They constructed their first car as an experiment in 1899. The founder, Alderman John Marston, J.P., was the son of an alderman who was mayor of Ludlow, Shropshire, almost on the doorstep of what was to become the Midlands motor-manufacturing industry in the UK.

John Marston was apprenticed at 15 to Edward Perry at the Jeddo Works in Penn Road, Wolverhampton, to learn the occupation of Japanware manufacturing. Having learned the craft, and much more besides, Marston set up on his own in 1859 at 23 years of age as a tinplate maker, doing it the easy way by buying two existing companies. Marston was a man of his time, stiff, formal, working all hours and expecting others to do the same.

The Sunbeamland Cycle Factory of Wolverhampton

When his old mentor Edward Perry died in 1871 he bought the ancient Jeddo Works, moved his interests there, and six years later founded the cycle business. Although a large heavy man he was a rider himself. The cycle business went on in a routine way producing an up-market machine with the famous Sunbeamland chain-case until 1899 when they suddenly branched out with two prototype cars, a single-cylinder and a twin.

The designer was Marston's assistant Thomas Cureton who was given a pretty free hand and actually put the car together from his own drawings before telling his bosses. He sent a curt and concise note to the board months after he had made the machine, in March 1900, saying that it could be put together in an empty works next door to the Villiers Cycle Company for an initial cost of £200 which would soon drop to £70, when it could be sold for £140. It would of course have the famous chain case.

The Sunbeam-Mabley

Marston had made his money and was 63, so it was Cureton who became the father of the Sunbeam car. The twin-cylinder was forgotten and the single four-horsepower model with horizontal front engine emerged as the first Sunbeam in September 1900. This was followed by the Sunbeam-Mabley voiturette which had the wheels in a diamond pattern. The curious Sunbeam-Mabley diamond-shaped car was the work of Mr Mabberley-Smith, a designer of ornamental ironwork. After this odd model the company formed a separate company to make the cars as distinct from the cycles, and although their cars were accused in the magazines of the day as looking like Panhards or Daimlers they were in fact Berliets with 'Sunbeam' stamped on the parts here and there. This came about because a Mr T. C. Pullinger persuaded Sunbeam to market the Berliet from Lyons under their own name although they were a little worried about the legal position regarding this.

The first model, the four-cylinder 12 horsepower, had a wooden chassis and was described by The Motor as a car of A1 quality at 500 guineas. The six-cylinder car joined the 12 in 1904 and was shown at the Paris Salon. The six was not a Berliet but Sunbeam-made and claimed to be the first British six, although S. F. Edge of Napier said he made the first six and two other firms also made claims. Curiously enough while Sunbeam were selling Berliet cars as Sunbeams they were also using Swiss Motosacoche engines in their Sunbeam motor-cycles. But Pullinger had gone to join Humber before Sunbeam even formed the board of their motor-making company, which they were a bit slow to do. So the directors of the new company were John Marston, Samuel Bayliss, the aforementioned Thomas Cureton, Dr Edward Deansley (who was married to a Marston), Henry Bath, and Herbert Dignasse, who had a motor business in London and became export manager of the Sunbeam organisation. The authorised capital was £40,000, not all issued.

Breton Louis Coatalen

By now Berliets were being sold in England, and the first genuine Sunbeam was the 16/20 of 1910/1911 designed by Pullinger's former assistant Angus Shaw. This was a side valve of 3828cc and Shaw himself drove one from John O'Groats to Land's End (1,756 miles) under official observation without stopping the engine and managed 22.8 mpg. He then planned to make ten a week. It was around this time that Breton Louis Coatalen entered into Sunbeam history, having already made a name for himself with Humber and then Hillman. He would stay with Sunbeam for 20 years from 1908 to 1928.

The Sunbeam Nautilus and Toodles II

Coatalen's first brainchild was the 14/20 - this was supposed to have been a three-cylinder car, but when it went into production there were four. Coatalen next produced the 12/16 horse power of 80 x 120 mm with four cylinders. But before this he began driving a Sunbeam at

Brooklands in Nautilus, which looked like a barrel with wooden slats fixed on hoops on the single-seat body with brass cones at each end. He had four overhead valves per cylinder, a great novelty for I909, worked from low camshafts through whippy pushrods. It was not too good. Nautilus gave place to Toodles II with a single chain-driven ohc working all valves. This one worked and won many of the races it entered.

Coatalen was all things to all men. He designed the cars, made them and raced them. He was a rugged individualist full of not always good ideas, and brought in worm drive with canted engines to accommodate the drive-line in 1910, but it lasted only one year. This way he got rid of the famous chains and chain-cases, and brought in normal shaft drive. He also moved the oil-pump down into the sump where it would become a popular position on most cars even to this day. He was also addicted to very light slipper-type pistons, but persisted in the long-stroke engine which later knowledge more or less outlawed. He was also a pioneer of the shock-absorber when most people just put up with the bouncing.

Sunbeam Mabley, the very first Sunbeam, powered by a 326cc single-cylinder engine.

Sunbeam Mabley, the very first Sunbeam, powered by a 326cc single-cylinder engine.

1904 Sunbeam 12 HP Runabout.

1904 Sunbeam 12 HP Runabout.

1904 Sunbeam 12 HP Tourer.

1904 Sunbeam 12 HP Tourer.

1915 Sunbeam 16 HP powered by a 3016cc engine.

1915 Sunbeam 16 HP powered by a 3016cc engine.

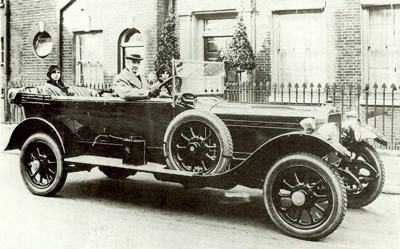

1921 Sunbeam 24/60 HP with the Earl of Lytton at the wheel.

1921 Sunbeam 24/60 HP with the Earl of Lytton at the wheel.

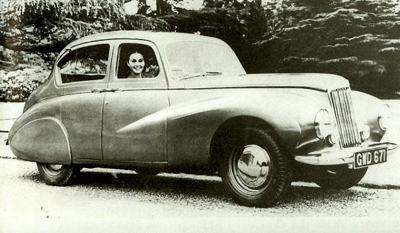

1949 Sunbeam-Talbot 2 liter, which was also available in drop-head form.

1949 Sunbeam-Talbot 2 liter, which was also available in drop-head form.

1954 Sunbeam-Talbot Mk III, powered by an 80 bhp engine and with a top speed of 95 miles per hour. It remained in production until 1957.

1954 Sunbeam-Talbot Mk III, powered by an 80 bhp engine and with a top speed of 95 miles per hour. It remained in production until 1957.

1964 Sunbeam Rapier Series IV.

1964 Sunbeam Rapier Series IV.

1969 Sunbeam Alpine, based on the Rapier body shell.

1969 Sunbeam Alpine, based on the Rapier body shell.

The old series Sunbeam Rapiers were also available in drophead form up until 1963.

The old series Sunbeam Rapiers were also available in drophead form up until 1963.

|

The French Coupe de l'Auto at Dieppe

It was Coatalen who was the architect of Sunbeam's famous 1, 2, 3 win at the French Coupe de l'Auto at Dieppe in 1912. He went to great trouble over preparation of his standard 12/16 for the voiturette race which was run simultaneously with the Grand Prix. He lightened the cars, improved cooling, reduced wind resistance. One car failed but the other three were in the money to the tune of £400 and the Coupe de l'Auto. Coatalen won boat-races, he sent a two-year-old 30 hp Sunbeam to Indianapolis where it finished fourth in the 500-mile race after an incident free run in 1913. Racing and record-breaking continued, and in 1913 Coatalen produced a one-off 12-cylinder aero-engined car driven at

Brooklands by Chassagne which took all world records from 50 to 1,000 miles and did a lap at 117.46.

The following year Sunbeam fielded a team of DOHC 3298cc cars for the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy which were said to be copies of Peugeots designed by the famous Swiss Henry. They had four valves per cylinder, hemispherical heads, and ball-bearing cranks. Peugeot were not there. K. Lee Guiness won for Sunbeam at 56.4 over the 600 miles and did the fastest lap at 59.3. July brought their prewar swan song before fighting started, with the Englishman

Dario Resta fifth behind the three works Mercedes and a Peugeot. When the war ended Marston had died and Cureton was in the chair, but a sick man. Coatalen resigned as joint managing-director and took the title of chief engineer, and took off for France for extended testing of the first postwar six, the 24, which was based on the old but bigger 25/30.

James Todd of Talbot-Darracq

At this time the board of the company were looking for a figurehead who was known in the world of business and manufacturing to take over as managing director. They were introduced to James Todd of the French Talbot-Darracq firm at Suresnes, and after negotiations Sunbeam ceased to be a separate entity and in 1919 became a part of STD Motors Ltd, which in turn failed and was bought by Rootes, who were in turn swallowed by Chrysler. Coatalen continued his racing programme, but now for STD rather than for pure Sunbeam, although he continued to use Sunbeam cars. Even during the war when he was busy with 22 different variations of aircraft engine he constructed two racing cars to run in the United States in 1916, before that country came into the war.

These cars were just under five liters (4708cc) which was the upper limit (300 cu ins) for the races at Sheepshead Bay, New York and at the better-known Indianapolis track. A Belgian pilot, Jean Christiaens, who had escaped from the Germans, was one driver and later took over the experimental department at the works, but was killed within sight of the gates during a driving exercise. Great names kept joining the Sunbeam camp, and now it was Rene Thomas and

Dario Resta who took over, but Major Segrave also drove Sunbeam, although it was becoming a little confusing to the casual observer with the STD banner including Sunbeams, Talbots and Talbot-Darracqs all being run, and sometimes under different names in different countries.

The Virtues of Light Alloy

Around this time Coatalen and the Sunbeam designers were convinced of the virtues of light alloy - which Coatalen had used during the manufacture of wartime aircraft engines, and after a succession of alloy blocks for engines Sunbeam produced the 14 horsepower which ran for four years, equipped with not only a lightweight engine block but gearbox casting in the same material. Another Sunbeam oddity for years was a long train of water pump, dynamo and magneto in line all turned from the front chain. Sunbeam were said at this time to have financial problems although they were producing and selling as never before.

At this time Talbot, who had arguably the most modern automotive factory in the world (located at Barlby Road in the UK), and which even made its own power, had money troubles which were to have a knock-on effect on Sunbeam. Meanwhile Darracq were selling the same car as Talbot (the French-designed 8) from Acton. Whatever the truth, the problem for the combine was that people were not buying many of either. But Coatalen was not concerned with the headaches of Georges Roesch, who had joined Talbot from Renault and was wrestling with the Anglo-French entwinement of factories, models, money and profits or losses. The Breton had money for his racing, his first love, and now the Swiss Henry, whose Peugeots friend Coatalen had been accused of copying in 1914, joined Sunbeam from the French firm Ballot.

At a car show some Sunbeam enthusiasts recounted a story that the first 1.5-liter Talbot-Darracq racers, which did well at Le Mans when the new voiturette formula began in 1922 (1, 2 and 3) were made of half a Sunbeam straight-eight engine as used at Le Mans, but when you search through the articles and documents of the era it is very confusing as to who stole what from whom. Certainly with the advent of Henry came also the two-liter Grand Prix formula, enforced for the first time at Strasbourg in July 1922. He went for four-cylinder cars with cast-iron blocks - none of Coatalen's alloys - smaller exhaust valves than inlets, and plain big-ends but roller mains. Top-line drivers Chassagne, K.L.G. and Segrave all broke their valves.

The Golden Days of Motor Racing

This was in the golden days of motor racing when Lee Guinness would load the Sunbeam and Talbot cars on to his private yacht, a converted trawler, and sail them all around the Mediterranean to race at points in Spain, Sicily, Italy and any other pleasant place. Many stories are told of the goings-on, one that when Segraye and his riding-mechanic dropped a valve and kept catching fire on the corners the impertubable Louis Coatalen told them to step out and put out the fire in their shoes in the nearest puddle. Segrave made fourth place on this, the Barcelona Penya Rhin circuit with blistered feet on three cylinders. In the

Targa Florio, Chassagne was said to have filled up plenty of local olive oil when his supply was lost through a fractured pipe.

Another of Coatalen's preferences was for dry-sump, and in the Sicilian hills all the oil ran back away from the scavenge-pump pickup at the front, with resultant bearing troubles. There was never a dull moment with Louis. Sunbeam racing and record-breaking history alone would take more words and space than people reading internet articles can be bothered with, but highlights were with the big names like Lee Guinness and Segrave. The former collected 126 records with the big 12-cylinder car in 1922 at Brooklands, and Segrave won with the old Indianapolis car and with a two-liter Grand Prix model. Another great racing driver,

Dario Resta, opened up a New York Branch for Sunbeam.

Vincent Bertarione

One of Coatalen's ideas which foreshadowed the kind of research which is going on half a century later related to finding out about suspension problems and needs. He fixed lamps to the rear hubs, the wings, and a passenger's shoulder and drove past an open camera shutter at night to record lines of light. At one point they bounced over a two-inch high obstacle, and all the variables like springs, shock absorbers and tyres were switched about to produce more comprehensive results. He was trying to reconcile racing needs with touring and produce facts on which to base a better suspension system. Next on the scene was Vincent Bertarione from Fiat, and after his designed Sunbeam had won the 1923 French Grand Prix once again tongues wagged and said he had obviously brought his late employers' drawings with him.

Coatalen had not been that pleased with Henry, in spite of his previous fame, but he could not complain about his latest protege, Bertarione, who had almost instant success. He produced 108 horse power from his six-cylinder racer, compared with only 88 from Henry's four of 1922, only one year later. Segrave danced up and down with joy at his Tours win the French GP as he was a great patriot who was much pleased if he could drive a British car, even if it was produced by a mixture of French, Italian and Swiss talent. Sunbeams took something of a rest from racing after their 1, 2, 4 in the French GP as supercharging seemed to be the winning thing in later events that year, and they were not equipped to cope.

Ten Year 8% Guaranteed Notes

As a side issue of the STD combination a Sunbeam called the 12/30 appeared at the 1924 London show without front wheel brakes, and appeared to be a copy of the then current Darracq. It survived only the following year. At this time STD were again afflicted by the shortage of funds which eventually led to their downfall. They issued ten-year eight percent Guaranteed Notes for £500,000 and in a financial report said assets were more than £2,250,000. Profits of Sunbeam were shown at £ 101,000 of the total year's figure for 1924 of £135,000 for the group, which now consisted of eight companies.

At this time too the most famous Sunbeam model of all time, the three-liter sports car, was announced to sell for UK£950 in chassis form or UK£1,100 complete, but we cannot find any evidence that it actually hit the market until 1925 or 1926. Contemporary reports said the car was more refined than lively, although it could be ordered with a supercharger. This is surprising, as it was the first twin-overhead cam engine offered for sale in Europe, was said to do 90 mph and to be able to beat a three-liter Bentley which was much heavier. The three-liter of 75 x 110 with gear-driven camshafts produced 90 bhp at 3,800 rpm.

The Sunbeam Three-Liter Sports

The car suffered from an overlong wheelbase at 10 ft. 10 in. and a narrow track, and it was reported that the chassis was not up to the rest of the design. It used Coatalen's preferred cantilever rear springs, although most engineers regarded them as better suited to heavy formal coachwork than for a light sporting carriage. The three-liter was overshadowed by the three-liter Bentley and the 30/98 Vauxhall, although Sunbeam fans will will email us to let us know how wrong we are. It did not do much in competition as high-speed handling was suspect, although it did finish second at

Le Mans in 1925 when the Bentleys had fallen out, and won some

Brooklands races. When the blower was offered in 1928 it was said to put out 138 horsepower at the same peak of 3800 rpm, although this seems an enormous increase from 90 bhp. Naturally reliability suffered with forced induction.

Sunbeam were ahead of their time in offering a 'detuned' racing car as it followed the best contemporary racing practice except for the use of cantilevered rear springs, but the cars were not as tough as the heavier, more rigid and slower Bentleys and Vauxhalls and not as many seem to have survived, as have examples of the other two makes. Very few blown models were made or sold, but there is evidence in old car journals and magazines that those lucky enough to have driven both blown and unblown models remember with affection the lightness of control - Sunbeam steering was always precise - and sweetness of the small six-cylinder engine.

Louis Coatalen vs.

W. O. Bentley

Coatalen then became engaged in a heated exchange with W. O. Bentley (if reported correspondence between the two is to be believed) - on the merits of racing for improving the breeding of cars. W. O. held that racing cars were entirely different and nothing to do with road cars. It is reported that Coatalen said Mr Bentley's firm was very young and his experience limited, and on that kind of note the exchange of vitriolics went on for some time and nobody convinced anybody else of anything. Sunbeam did in fact put their three-liter sports car engine into two standard 16/20 chassis and enter them for the

1924 Le Mans but they were not ready in time.

When the firm got around to supercharging their racing cars, once again Coatalen went his own way. Everyone else (Fiat, Alfa-Rorneo, Mercedes, etc) blew the compressed air through the carburetor, whereas Sunbeam sucked the mixture from the carburetor and pushed the ready-mixed fuel/air into the engine. This had the effect of pushing in a cooler mixture.

Duesenberg had in fact used this method to win the 1924 Indianapolis race, but it was not known in European competition. Unhappily when the blown Sunbeams came to the line in the 1924 French Grand Prix at Lyons they were basically the previous year's winning cars and the fastest there, but they all fell out, mostly with magneto trouble, which Coatalen later explained was due to broken wires in the mags.

The End of Sunbeam Racing

Meanwhile the sporting three-liters did start at

Le Mans in 1925, but had broken chassis, stuck throttles, and dashboards adrift from the weight of duplicated instruments. Nevertheless Chassagne/ Davis finished second with 1343 miles behind them, 45 miles behind the winning Lorraine. The road cars continued to be well-made and offering novelties like an adjustable steering column on the popular 14/40 of 1926, which cost £60 less than the previous year at £625, for either two-seater with dickey or five-seater tourer. Racing stopped in 1926 as no shareholder dividend had been paid for a number of years.

Coatalen was supposed to be designing a new small car, which turned out to be Roesch's 14/45 six-cylinder Talbot. People like Segrave continued to race the older cars but no new ones were being made. Financially things were going from bad to worse as the various factories within the STD group kept each other in ignorance. Sunbeam produced a new 16hp car which cost £100 more than the Talbot offered at the same time. Coatalen was now mostly in France, while Roesch had returned to England after two years over there.

The famous 1000 horsepower record-breaker was proposed to bring world-wide publicity at lower cost than racing. This had both front and rear engines and was designed to beat the 200 mph mark. Segrave paid his own way to the 23-mile straight at Daytona, Florida, as Sunbeam thought it could be done in England, but he said it was his neck at risk and he would choose the venue. In the event Segrave did 203.7928 mph. He used, as said earlier, two 500 horsepower Matabele aero engines of 44,880cc in all in a four-ton car 20 feet long. Final drive was by chain under armoured covers. It was also Segrave who drove the V12 Sunbeam Tiger in 1926 at Southport to achieve 152.33mph from only four liters, but the Tiger weighed only 18 cwt.

Malcolm Campbell

But Sunbeam's first record-breaker, the 18-liter V12 which did 146.16 mph in 1924 and 150.87 mph in 1925 was driven by Major Segrave's arch-rival

Malcolm Campbell, who had 350 horsepower at his disposal. was the same car which K. L. Guinness had driven at 133.75mph in 1922 at Brooklands to take the world record. This machine had aluminum pistons, three valves per cylinder (two exhausts) SOHC to each bank of the Vee, twin plugs and dual magnetos, two carburetors, eight main bearings, and a giant flywheel nearly two feet across. This was the last car to take the record at

Brooklands, and the first of the five successful Sunbeam attempts on the land speed record.

Thus as the racing and record-breaking died away, Coatalen began to take a back seat and Roesch came to the fore as things moved on to the final crash and the receiver. Did Sunbeam bring down Talbot or vice versa? It is certainly clear that Sunbeam were making the profits up to this stage, but then the new generation of Roesch Talbots which ran up from the 65, 75, 90, and 95 to reach their climax in the 105 and 110, began to make money. For some obscure reason Sunbeam were never paid for some World War 1 aircraft engine work, which started the rot. But, in any case the company could hold its head high in any motoring setting with their record of achievement in racing, record breaking, and innovation as well as in the production of outstanding road cars.

Their last model, the Dawn of 1933/34, was their worst. The prototype eight-cylinder of 1937 was never made. A monster known as The Silver Bullet was made for Kaye Don to drive in 1930 in a land speed record bid, powered by two V12s one behind the other. Each motor was of 24,000cc. It was an enormous and complex affair with superchargers, but in the end it did not handle even in a straight line and was eventually sold to Freddie Dixon, who achieved nothing with it. It was said to have cost £15,090. Someone eventually woke up to the complexities and confusion of STD, and independent auditors found in 1931 that there was a lack of coordination. The directors resigned.

Just before the fateful Dawn model came the so-called Speed Twenty Sunbeam, which was a rehash of 1926 engines made for the 20 allied to a no longer popular item, the crash gearbox. It was an out-of-date car for 1933. In 1935 the STD combine finally collapsed and was bought from the official receiver by Rootes, who already held a debenture. They ceased making Sunbeams, and eventually merged the name with Talbot to make what was really a Humber but was called a Sunbeam-Talbot. Looking back on the marque, perhaps their weakness was that they were too well-made and cost too much money when cheaper cars of lesser quality became available, and also that the man in the street was not nearly as impressed with racing and record-setting achievements as he might have been, and registered his clear and decided preference for no racing and a cheaper car.

The Resurrection of Sunbeam

The Sunbeam marque was resurrected in a sports car sense in 1953 when the brilliant two-seater “Alpine” was announced. The Alpine was based on the chassis and running gear of the Sunbeam-Talbot 90 saloon, and as such was in reality an entirely Rootes affair. To address scuttle-shake the frame was stiffened up with extra side plates, and the nose of the car was exactly like that of the saloon. The Alpine featured independent front suspension by coil springs and wishbones; at the rear a rigid axle was located by half-elliptic leaf springs. The four-cylinder 2267cc engine developed 80bhp at 4200rpm, power being delivered to the rear wheels via a four-speed gearbox with the shifter located, as was the fashion of the day, on the steering column.

The Alpine was soon enjoying success in competitions such as at the Coupes de Alpes Alpine Rally, where the team cars won four separate events. Then Stirling Moss would use Alpines in 1953 and 1954 to become only the second driver in history to win a Coupe d'Or for three consecutive 'clean' runs on this difficult event. But after two short years the Alpine was discontinued in 1955, but just why the powers to be at the Rootes group came to this decision we remain unable to fathom. One possible explanation is that Rootes had been busy developing the Sunbeam “Rapier”, and thought the marque required only one “hero car”. In what can best be described as a public relations disaster, the Rapier name would be dropped in favour of Alpine in 1959. The new car could best be described as a “bitsa”, using the Rapier Series III running gear and suspension, fitted to a shortened version of the under-pan, all draped in a lovely two-seater body she with prominent tail fins.

The Sunbeam Alpine

Despite the ‘new’ Alpine only having a 1494cc 4 cylinder engine it came tantalizing close to cracking the holy grail of 100mph (161 kmh), on the down side was the fact that it took a leisurely 13 seconds to reach 60mph from rest. With a smaller engine capacity than its main rivals, such as the MGA/MGB and Triumph TR series, the Alpine was invariably overshadowed and often overlooked. What a shame though, for the styling was and remains worthy of earning the car a much greater place in automotive history.

The Alpine would enjoy a reasonably long life-span, built from 1959 to 1968 and growing up to Series V which was fitted with a 1725cc engine. The purchaser could option the “overdrive” transmission, and there was even a short run of Automatics built. And, to help make the Alpine more appealing to a broader motoring public, it could be ordered in either open sports or closed hardtop versions. There were also a few fastback conversions manufactured, with Rootes approval, by Harrington of Sussex. This type of Alpine had a limited, but creditable, competitions career, which included winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency award at Le Mans on the first of three visits in 1961.

The Sunbeam Tiger

But there were those that lamented the Alpines lack of power. Ian Garrad was one such person; the son of then competitions manager Norman Garrad, Ian was the Rootes company’s Californian representative - and was well aware of the way that Carroll Shelby had transformed the AC Ace into the Cobra with a Ford V8 engine transplant. Garrad enlisted the help of Ken Miles, and together they effected a similar transplant to that of the AC. Their choice of engine was the Ford 4.2 liter 164 bhp unit, and they then shipped their “prototype” back to the UK headquarters. The Rootes management were impressed, and well should they have been – for the choice of engine meant there were absolutely no visual outer skin panel changes required to fit the lusty V8 engine!

The modified Alpine was dubbed the Sunbeam “Tiger”, and assembly moved to Jensen at West Bromwich. The engineers soon discovered just how well sorted the Alpine was, finding the body well able to handle the huge increase in torque. Naturally the Tigers performance humbled the Alpine. The 0-60mph dash was down to a very respectful 9.5 seconds, while the car was good for a top speed of 118mph (190 kmh). The factory made one attempt race the Tiger – at the 1964 Le Mans – but both cars that were entered retired early with engine failures. Nevertheless others thought the car had rally potential. One was entered by privateer Peter Harper's in the 1965 Monte Carlo Rally, but as luck would have it his sixth placing was disqualified after scrutinizers found illegal technical modifications had been made to the car.

In 1967 the 4.7 liter series 2 Tiger would be released, but shortly afterward Chrysler would acquire the Rootes group and the new management would choose to bring production to a premature end. Most commentators of the day acknowledged the takeover of Rootes by Chrysler would always be the downfall of the Tiger, simply put it would be somewhat embarrassing for Chrysler to manufacture a car and install a Ford engine.

Also see: Lost Marques - Sunbeam (AUS Edition) |

Sunbeam Car Reviews