The Car That Made Good in a Day

At the time, it was known (unfairly) as the 'car that made good in a day', but Harry C. Stutz had been designing cars for fourteen years or so before the first vehicle to bear his name appeared. He started with a crude gas buggy in 1897, then progressed to the low-built American Underslung of 1907, in which the chassis was hung below the axles.

The First Indianapolis 500

Stutz later went into component manufacture, and one of his specialities was a robust three-speed transaxle unit, which combined a gearbox and final drive in one casing. To prove the quality of this back-axle assembly, Stutz built a racing car - in five weeks - and entered it in the first-ever Indianapolis 500 in 1911. The car, driven by Cal Anderson, finished eleventh, and the marque's reputation was established.

The Ideal Motor Car Company

The company producing the Stutz car was known as the Ideal Motor Car Company, and its factory was in Indianapolis. In 1913, the corporate name was altered to the Stutz Motor Car Company of America. There was little remarkable about the first Stutz cars, which were powered by 6.3-liter Wisconsin engines, although the marque continued its sporting career, achieving fourth and sixth places in the 1912 Indianapolis 500, first and second places in the Illinois Trophy at the Elgin racetrack, and third place in the Milwaukee Grand Prize.

The Stutz Bearcat

In 1914, however, the archetypal Stutz, and one of motoring history's most legendary models, was born. It was the Bearcat, whose name was symbolic of the early 1920s (although by that time, the Stutz Bearcat was becoming a little passe). The original Bearcat was similar to the

Mercer Raceabout formula of massive engine, minimal coachwork - bonnet, wings, two seats and a bolster fuel tank were deemed adequate - and proved remarkably popular, with sales rising from 759 cars in 1913 to 2207 in 1917.

The White Squadron

One reason behind the fame of the Stutz at this period was the success of the White Squadron of racing Stutzes in the major races of 1915, although these cars, with their specially built sixteen-valve 4851cc Wisconsin single-overhead-camshaft engines were far from being standard models. The White Squadron cars were third, fourth and seventh at Indianapolis, first and second at Sheepshead Bay and won the Point Loma, Minneapolis and Elgin events, while the team's leading drivers, Earl Cooper and Gil Anderson, were first and third in the National Drivers' Championship for the year.

Cannonball Baker

In 1916, Cooper came second in the

Vanderbilt Cup, and the following year won a 250-mile race at the Chicago Board Speedway. The year 1919 saw Eddie Hearne take second place at Indianapolis, but the White Squadron cars were now past their best, and faded from the scene. On the road, too, the Stutz was breaking records: when a dissatisfied owner took his car back to the supplying dealer, protesting vehemently that this totally gutless new 1916 Bearcat was no match for the smaller-engined Mercer Raceabouts on the streets of New York, the Stutz publicity department handed the 'dud' over to the larger-than-life Cannonball Baker, who had a seemingly insatiable urge to thunder across the USA from Atlantic to Pacific in high-powered cars, and announced that he would use it to break the Trans-American record which was then held by a motor cycle.

Break the record Cannonball did, taking eleven days, 7

½ hours to complete the trip. On one memorable day, he put 592 miles into 24 hours, and the car finished unscathed except for a broken shock-absorber bracket. Although the Stutz company was seemingly riding high, Harry Stutz resigned in 1919 and founded the HCS motor company, also Indianapolis-based. The HCS car was an expensive assembled car whose radiator and bonnet styling (but little else) were cribbed from the

Hispano-Suiza; the marque failed to make any great impression on the car-buying public, and quietly died in due course.

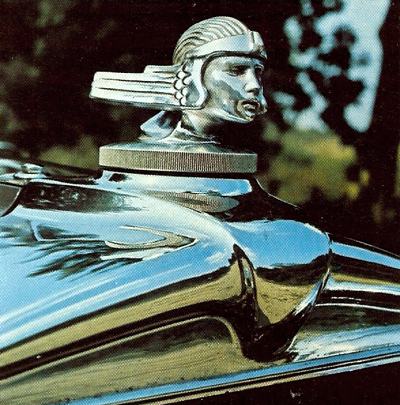

Stutz hood ornament.

Stutz hood ornament.

1923 Stutz Bearcat.

1923 Stutz Bearcat.

1927 Stutz Black Hawk Custom Series AA Tourer. It was powered by a eight-cylinder engine developing 110bhp.

1927 Stutz Black Hawk Custom Series AA Tourer. It was powered by a eight-cylinder engine developing 110bhp.

1929 Stutz Black Hawk Six 4 liter sedan.

1929 Stutz Black Hawk Six 4 liter sedan.

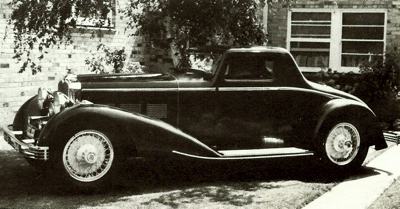

1932 Stutz short-chasss DV32 Super Bearcat.

1932 Stutz short-chasss DV32 Super Bearcat. |

Charles M. Schwab

The Bearcat had become more civilized by 1920, including the fitment of windscreen, doors and hood. Shortly afterwards, the gearbox parted company with the rear axle and went to live in the conventional position, and Stutz began making their own four and six-cylinder power units. The company had come under the control of steel tycoon Charles M. Schwab, but there was little evidence of new thinking at the top, and the last Bearcat, the 4.7-liter Speedway Six of 1924, had little to offer, and sales continued to fall.

There was a another change of management in 1925, when Frederic E. Moscovics took over as president, and brought in the Belgian designer Paul Bastien, who had previously worked for Metallurgique in his homeland. Bastien created a car that was intended to exemplify 'safety, beauty and comfort', but the new Safety Stutz Vertical Eight could not shake off the sporty image of its forebears that easily. Its 4.7-liter straight-eight engine was endowed with a single overhead camshaft, and developed 92 bhp at 3200 rpm, enabling the car to achieve 75 mph.

The Safety Stutz

The Safety Stutz had a worm-drive rear axle, which permitted the car to be built very low, while an advanced feature was the use of hydraulic four-wheel brakes (which really were hydraulic, operating on a mixture of water and alcohol). The car could be had with low-built

Weymann closed coachwork, or as an agressively beetle-backed speedster; crowning the handsome radiator was a mascot representing the sun god Ra, while the car was endowed with a primitive form of safety glass with wire mesh embedded in windows and windscreen! Altogether, the new Stutz was one of the outstanding American cars of its day and of all time, although its chances in an era when mediocrity was the order of the day seemed less than encouraging.

A Racing Revival

Moscovics relented of his decision to play down the sporty side of the Stutz, though, and entered the speedsters (known as Black Hawks from 1927) in a wide selection of races, which they duly won. The great sporting year of the Stutz was 1928. In that year, Gil Anderson drove one of the new 4883cc Black Hawk speedsters at 106.52mph at Daytona to set up a new American stock-car record. Although Frank Lockhart's attempt on the Land-Speed record with the ultra-streamlined Stutz Blackhawk ended in a fatal crash, it is worth remembering that this sixteen-cylinder Miller-engined car built in the Stutz factory was, at 3.1-liters, the smallest-capacity

Land Speed Record car of all time, yet achieved 225 mph on one of its unsuccessful runs, faster than the 88-liter White Triplex which had just set up a new record when Lockhart crashed.

It was a Stutz, too, that raced an Hispano-Suiza for a purse of $25,000 at Indianapolis, when Moscovics bet French coachbuilder Charles T. Weymann that a 4.8-liter Stutz could beat an 8-liter Hispano in a twenty-four-hour endurance race. But Moscovics should have thought better of the challenge, as after nineteen hours the Stutz packed up with valve trouble and the Hispano collected the prize money. It was nearly a different story at Le Mans that year, though, as

Weymann entered a team of three Stutzes to challenge the best sports-tourers of Europe, and the bold venture nearly paid off, as the car of Bloch and Brisson, which finished second to the 4

½-liter Bentley of Barnato and Rubin, had lost its top gear ninety minutes from the end.

Le Mans

It was the nearest an American car came to winning Le Mans until the Ford Mk IVs and GT40s came on the scene to win the 1966, 1967 and 1968 events. It was a result that fully endorsed the Stutz claim that 'the car which is safest has the right to be fastest', for the ailing Stutz had covered an impressive 1594.26 miles against the winning car's 1656-68 miles. In January 1929, the Stutz company issued a booklet describing the attributes of the Low-Weighted Stutz, 'The wide speed range, or flexibility, of the new car is a distinct factor not only because of congested traffic conditions, but also because the car performs throughout the entire range with perfect smoothness and ease of handling, and does not at any point give the operator the feeling of strain and overtaxed mechanism.

Low centre of gravity contributes largely to the safety of the car in that overturning in case of accident is practically impossible. Also, the increased roadability is particularly noticeable in terms of absence of side sway and the greater comfort. The low centre of mass of the new car is made possible through careful engineering, which has taken full advantage of the possibilities of the worm-drive axle. With full load, the floor boards are approximately 20 inches from the road, and it is only 70 inches to the top of the deck onclosed cars. This indicates the ample headroom, as well as the low construction of the car ... Long trips may be covered with a minimum of fatigue and nervous energy.'

Such considerations were not paramount when the Sutz cars for the

1929 Le Mans race were constructed, as these were fitted with superchargers between the dumbirons, feeding the single carburetor through a massive induction pipe several feet long. The cars were 'fearsome looking beasts ... capable of 105 or 106 mph ... blowers are chancy things and apt to smash up engines.' The best that one of the Stutz team could manage was fifth place. There were Stutz entries at Le Mans in 1930 and 1932 as well, but none of them finished.

The design of the straight-eight was further improved for the 1931 season, with the addition of a 'No-Back' device behind the gearbox so that the car could not run backwards when restarting on hills, and a 'Variable Booster Brake' which could be used to alter the amount of servo-assistance given to the brakes. The Motor explained: 'It is a simple matter to arrange that a comparatively light pedal pressure will produce the maximum braking effect if high speeds on good road surfaces are to be the order of the day. On the other hand, when driving in traffic over greasy roads, it is just as simple to reduce the servo action to such an extent that the full depression of the brake pedal will just fail to lock the road wheels.'

The Stutz Black Hawk

There was a new model, too, a cheaper ohc six-cylinder model marketed as the Black Hawk. Introduced in the hope of revitalising flagging sales figures, it was priced on the UK market at only £685 in chassis form, whereas the cheapest eight was £995 as a chassis-the dearest, a supercharged short-chassis variant which revived the Bearcat name, was £1195 in chassis guise. The US market was now becoming dominated by V12 and V16 giants from

Cadillac, Packard and

Lincoln, in the face of whose silken luxury a mere eight cylinders of Stutz seemed rough and uncivilised.

In response the last great Stutz power unit was introduced, the DV 32. 'In two-seater open form, the Stutz Bearcat is sold with a guaranteed speed of 100 mph', wrote The Motor in October 1931. 'The engine, which develops 155 bhp at 3500 rpm, has four valves per cylinder, these being operated by two overhead camshafts, and is the only power unit of its kind in the Show. The specification includes a nine-bearing crankshaft, centrifugal-pump circulation, forced lubrication, Schebler carburetor, air cleaner and purifier. The transmission system comprises a four-forward-speed "silent-third" gearbox built in unit with the engine, and final drive by underslung worm.'

The single ohc straight-eight and the Black Hawk Six were continued alongside this splendid new model, which rather eclipsed them with its technical specification even though it was too expensive for most customers. A free-wheel device was optional, and became standard equipment the following year, when the SV16 also came with thermostatically controlled vents in the bonnet which regulated temperature in the engine compartment, and there was servo-assistance for the clutch. A new feature on the 1934 models was a servo for the clutch withdrawal mechanism, while 1935 models had an automatic clutch allied to a three-speed transmission.

Although The Motor claimed cheerily that 'English admirers of the Stutz claim an affinity between this car and the high-quality British sports car', the days of the DV32 and the SVI6 were numbered, and in 1935 the Splendid Stutz ceased production. However, the company had taken out insurance in 1928 by starting to produce a curious light van, the Pak-Age-Car, with all-round independent suspension and a rear-mounted engine, but even this odd-ball machine failed to keep Stutz afloat for more than another three years, although the design rights were taken over by Diamond T Trucks.

Also see: Lost Marques - Stutz (AUS Edition)