Comte de Chasseloup-Laubat and his Jeantaud

The first impetus for Land Speed Record activity came from France and it was in France that the first attempt to set an Land Speed Record mark was made. It was organized at the behest of M. Paul Meyan, a founder of L' Automobile Club de France and a director of the magazine 'La France Automobile'.

Held in Acheres Park, north of Paris, on 18 December 1898, the contest was an open one and took the form of a standing start kilometre followed immediately by a flying kilometre. The formula was a free one in that any type of powered vehicle could enter provided that power was transmitted to the road via the wheels.

From a spectacle point of view the event was hardly the most exciting ever staged and in contrast to the 'barking, snorting, noisy petrol-powered vehicles of other competitors, the winner's vehicle was electric powered and therefore very quiet and totally unspectacular.

Nevertheless, the Comte de Chasseloup-Laubat in his Jeantaud, powered by a 36 hp electric motor covered the standing kilometre in one minute 12.6 seconds and the flying kilometre in 57 seconds, achieving an average speed over the second segment of 39.245 mph, to set the first official record.

Camille Jenatzy

Next came Belgian driver Camille Jenatzy. Unable to attend the first Course de Vitesse he issued a challenge of his own. It was held over the same course on 17 January 1899. On the day appointed, the challenger had the privilege of competing first. By covering his second. flying kilometre in 54 seconds at an average speed of 41.42 mph, Jenatzy became the first man to break the Land Speed Record.

His joy was shortlived, however, as Comte de Chasseloup-Laubat replied with a flying kilometre of 51.2 seconds recording an average of 43.69mph and destroying Jenatzy's record of ten minutes standing. After 10 days of intensive work, Jenatzy came to the line again and" cut his time for the flying kilometre down to 44.8 seconds gaining an average of 49.92 mph. By 4 March, Chasseloup had introduced a rudimentary form of streamlining on his car and was able to post a new average speed of 57.6 mph. But Jenatzy would not rest.

The First Land Speed Record Special, Janzais Contente

On 29 April 1899, he came to the line with Janzais Contente, a cigar-shaped projectile which was the first of the true Land Speed Record 'specials' built specifically for the event. The effort proved worthwhile and Jenatzy was able to leave the course with a record now standing at 65.79mph, the first time 60mph had been exceeded. From the cold plains of Northern France, the record breakers moved south to the Cote d'Azur and the famous Promenade des Anglais at Nice.

William K. Vanderbilt's Mors

It was on 13 April 1902, along this normal, pedestrian-lined boulevard that Leon Serpollet guided his steam-powered Oeuf des Paques at 75.06mph - his only form of braking being his engine! William K. Vanderbilt came over to France to try his hand and the American dollar in an attempt to wrest the record from European hands. Choosing a section of the Ablis-St Arnoiilt road and driving a road racing Mors, Vanderbilt eventually cracked the record with a 29.4-second flying kilometre - 76.08 mph - and became the first driver of a petrol-powered' motor car to hold the Land Speed Record.

The Automobile Club de France

By this time, the Automobile Club de France had taken upon itself the position of arbiter of who could and could not be adjudicated to have broken or not broken the Land Speed Record-a record which the Automobile Club de France seemed to believe belonged only to them. Luckily, the history of the Land Speed Record underlines the fact that two important components of the whole Land Speed Record spectacle failed to respect the ACF in this effort- the record breakers themselves and the general public. For the drivers, only the speed over either the kilometre or the mile was important and later years were to prove that the general public held the same, easily understood view of the event.

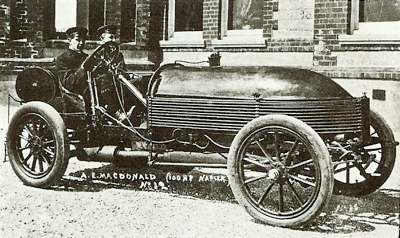

McDonald's 6 cylinder Napier L48, which set a Land Speed Record in 1905 at 104.65 miles per hour.

Bob Burman's Blitzen Benz, a 200hp car which set up the incredible world speed record of 142 mph in 1911.

1920 350hp Sunbeam Land Speed Record Holder.

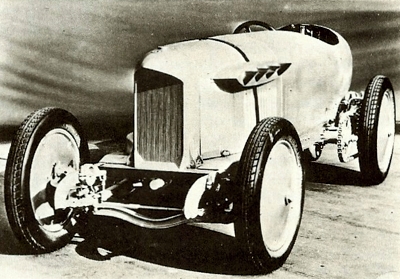

The 1927 1000hp Sunbeam. Driven by Seagrave, it was the first car to better 200 miles per hour.

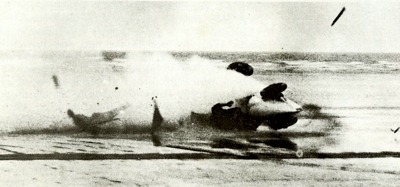

The attempt by Guilio Foresti on the Land Speed Record at Pendine Sands on 26th November 1927. Miraculously, Foresti survived.

All that was left from Lee Bible's fatal attempt on the Land Speed Record, in his White Triplex Special, at Daytona in 1929.

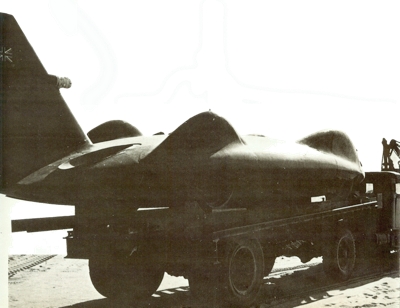

Donald Campbell's Bluebird arrives at Lake Eyre, Australia, prior to his land speed record attempt. His efforts were successful and he finally achieved a speed of 403.10 miles per hour.

Art Arfons Green Monster. Although a crude device, it was extremely effective. In October 1964 Arfons recorded a speed of 434.02 miles per hour and later that month pushed it up to 544.13 miles per hour. Both these runs took place at Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. In November 1965 Arfons returned to the salt flats and achieved a speed of 576.55 miles per hour.

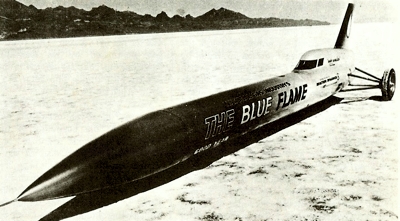

Gary Gabelich's Blue Flame. This machine was developed by the Illinois Institute of Gas Technology in conjunction with the Institute of Gas Technology. At Bonneville in 23rd October 1970, Gabelich established an average speed of 622.407 miles per hour.

|

The Florida Speed Week

Vanderbilt was still keen and with his money he could afford to travel around looking for perfect conditions. He found them in the warmth of Eastern Florida at a place called Daytona which featured a beach some 23 miles long interrupted only by a river and a pier. The Florida Speed Week was inaugurated there in 1903 and it was in 1904 that Vanderbilt had another crack at the Land Speed Record, this time in an 11.9-Iitre Mercedes '90', a superbly proportioned racing car of impeccable motor-racing antecedents. These proved sufficient to enable Vanderbilt to raise the record to 92.30 mph.

Louis Rigolly's Gobron-Brillie

However, the French were not idle and they too had their speed week or Semaine de Vitesse at Nice. It was in 1904, just two months after Vanderbilt had culminated the Daytona Speed Week with his record that a Gobron-Brillie was brought to the line at Nice with a 130 hp 13.6-Iitre engine. Driven by Louis Rigolly with the minimum of fuss and minus any cowling for the engine, the car covered the measured kilometre at a speed of 94.78 mph. The magic 100 mph was getting nearer and nearer, presenting a new and specific challenge to all the interested parties. So it was that in July 1904, the Gobron-Brillie flashed over a course on the Ostend-Nieuport road in Belgium to record 103.56 mph.

Activity in the sphere of the Land Speed Record continued to occupy the minds and talents of both constructors and legislator alike. Some record attempts were doomed to failure by sheer mechanical ineptitude or just simple bad luck, others were doomed to non-recognition in official circles. Development was quick and in many cases quite effective though. The Gobron-Brillie record stood for only four months until Paul Baras driving a Darracq which featured a steering-column gearchange broke the record and set a new speed of 104.52 mph.

By 1905 though, the world of the Land Speed Record was beginning to be inhabited by strange, outlandish vehicles which bore little resemblance to normal racing-car pracrice, the true Land Speed Record Specials were in embryo. First to appear is generally recognised as being a 22.5-liter Darracq which used two four-cylinder engines bolted together to become the forerunner of the V8 engine. Crude it may have been but the concept was good enough to cut a kilometre at 109.65 mph.

A Stanley Steamer Clocks 127.6mph

Steam as a power was not finished, either, and in 1906 a Stanley steam-powered motor car, Rocket was piloted through a measured mile at an astonishing 127.6mph - and that from a car that weighed in at 14.5 cwt. The same car was used in 1907 for another attempt on the record but crashed. Speeds were getting too high for the human mind and body to record accurately as the decade began to draw to an end, and no-one wanted a record attempt to founder simply because of human timing error. First to profit from the introduction of electric timing for the Land Speed Record was Victor Hemery driving a 21.5-liter Benz to a record of 129.95 mph.

L. G. Hornstead's 200 hp Benz

The introduction of the two-way rule allowed L. G. Hornstead in a 200 hp Benz to set a record of 124.10 mph at Brooklands, the run being accepted by the Association International des Automohile Clubs Feconnus (AIACR) superseding Hemery's faster time! Official-type record breaking continued to be a source of much amusement, as others, Europeans in particular, struggled to attain and then surpass speeds already recorded previously. For instance, Rene Thomas in a V12 10.6-liter 280 hp Delage turned in a speed of 143.31 mph on a public road in France while Ernest Eldridge in a real monster of a special Fiat called Mephistopheles recorded a speed of 145.20 mph over the same course but was disqualified as he lacked a reverse gear on his car.

Ernest Eldridge's Fiat Mephistopheles

Eldridge did fit one, though, and on 12 July 1924, he set a new and official Land Speed Record at 146.01 mph - the highest speed ever set on a public road in the history of Land Speed Record activity. Following Eldridge's magnificently brave effort, the English entered the fray with a vigour and enterprise which was to keep the world interested until the 1960s. Malcolm Campbell became almost obsessively interested in the Land Speed Record and made an unsuccessful attempt on the record at Fanoe Beach in Denmark, an attempt that ended in tragedy when a tire flew off at speed and killed a spectating child.

Malcolm Campbell

Eventually, Campbell broke the record at Pendine Sands in Wales, by a mere 0.15 mph, but an appetite was whetted that was not satisfied until Campbell was a comparatively old man and the bug had been well and truly passed on to his son. On the political front of the sport, the year 1924 was a turning point. The AIACR laid down clear, concise rules which won the approval and therefore acceptance of all concerned. Runs were to be in two directions, the average gradient of a course was to be no more than one per cent, the two runs had to be completed within a given time limit (originally 30 minutes) and the measuring instrumentation had to be accurate to 1/100th of a second.

Louis Coatalen's Sunbeam

There were other rules, including those dealing with the way power was to be used, ie through the wheels, but at least the sport had an international framework through which it could work. By July 1925, Campbell was back at Pendine to set a new average of 150.87mph over the mile - a small increase, but he still held the Land Speed Record. There was a challenger waiting in the wings, though. Louis Coatalen of Sunbeam was interested in the Land Speed Record, mainly as a publicity device for the company but also as an engineer responding to a challenge.

Always mindful of what was possible and what was feasible, Coatalen's design was a masterpiece in economy and ingenuity. He used twin, two-liter, six-cylinder engine blocks to provide the basis for a 75-degree V12 engine which, in supercharged form, would provide 306 bhp at 5300 rpm. With an all-up weight of 18 cwt, the car's theoretical maximum was 160mph. Following some rather difficult teething troubles involving supercharger casings and. other sundry problems, Coatalen's car, driven by Henry Segrave, eventually recorded an average of 152.33 mph on Southport Sands to beat Campbell's figure with a car powered by an engine one-quarter the size of Campbell's mount.

John Parry Thomas' Babs

Yet another engineer, the taciturn John Parry Thomas, designer of the superb Leyland 8, was also building himself a special car around this time. Short of cash, Parry Thomas had bought the old Higham Special for £125 after Count Zborowsky's death and had patiently refurbished it, using as a power unit a 26.9-liter V12 Liberty aero engine. A brutal monster Babs may have been but it was an effective one and on 28 April 1926, Thomas drove it at 171.02mph.

However, there was to be no denying of Campbell's restless urge. He took it upon himself to build another Bluebird, the name which he used for all his record-breaking machinery. His new vehicle was built around a chassis designed by Amherst Villiers and was powered by a 22.3-liter Napier Lion aero-engine which featured 12 cylinders disposed in three rows of four - rather like an arrow head in formation. The target for this car was to be three miles a minute - 180 mph - a brave venture which partially succeeded but failed in its ultimate. After some really bad weather, Campbell eventually recorded 174.88 mph for the flying mile, bringing 180 mph tantalisingly close.

The 1000hp Sunbeam

Coatalen was to prove almost implacable in his efforts. With 200 mph as the next real barrier of public significance in mind he had built an absolute monster of a vehicle powered by two Sunbeam V12 Matabele aero engines, each of which developed 435 bhp at 2000 rpm. Called the "1000 hp Sunbeam", the car weighed in at 3 tons 16 cwt and its driver, Henry Segrave, was diplomatic enough to get the AAA to join the AIACR, thus ensuring absolute security for the Land Speed Record if he was to gain it at Daytona.

Skilled and courageous, Segrave was also confident and far-sighted, the car eventually performing before 30,000 spectators and setting a mile record of 203.792 mph. Like a red rag to a bull, the new figures acted on Campbell and by February 1928, he was back in Florida with a redesigned Bluebird. After some problems brought about by hitting a ridge at very high speed, Campbell eventually brought Bluebird to the line on Sunday, 19 February. His first run nearly ended in disaster when a bump forced his goggles off his face but he still turned in a speed of 214.7 mph. His second was uneventful but slower at 199.9 mph. However, the average was 206.956 mph, so Malcolm Campbell was once more the record holder.

Frank Lockhart's Streamlined Stutz

On the indigenous American scene things were still happening also. In particular, there were two strong challengers ready for battle. One, a streamlined Stutz designed and driven by Frank Lockhart, and the other, a brute of a machine called the Triplex Special, which was to be driven by Ray Keech. The Stutz was a superb piece of engineering, small, light and very handsome. Despite a capacity of only three liters it was calculated as giving 385 bhp for a car weighing only 25 cwt. In contrast, the Triplex Special used no less than three 27-liter Liberty aircraft engines. Initially, both cars tried for the Land Speed Record at the end of the 1928 Florida Speed Week.

Lockhart survived a bad accident and Keech was badly scalded when a water hose burst. But they both had every intention of returning. Keech was back in April with a very slightly modified car. He recorded an average over the two-way flying mile of 207.552 mph and a very brave man had brought the Land Speed Record back to the USA. Neither Campbell nor Segrave were happy with the Land Speed Record being in American hands. Segrave, in particular, was almost beside himself in his efforts to create a new, better, quicker machine with which to regain his record.

Seagrave's Napiers

So, another car was commissioned, this time designed by J. S. Irving. Segrave hired a specially prepared engine from Napiers which was originally intended for use in the Schneider Trophy Air Races. This new unit provided 925 bhp at 3300 rpm and Segrave was confident that with a new streamlined body with less frontal area he would be able to regain the Land Speed Record. Almost anti-climatically he did so and in front of 120,000 spectators at Daytona Beach on 11 March 1929, averaging 231.446mph. Segrave was knighted soon afterwards.

Campbell then made several abortive attempts on the record at Verneuk Pan in South Africa, with much help from that country's government, before moving to Daytona in a re-designed Bluebird - this time with the aim of exceeding 250mph for the first time. He achieved 246.09mph, both runs being accomplished in under five minutes, making it one of the smoothest and best-organised conquests ever. That exploit confirmed Campbell in the eyes of the public as almost a demigod of speed and his importance and popularity was acknowledged by a knighthood.

Campbell's Bluebird

Even that was not enough for Campbell, though, whatever it was that drove him on was powerful enough for him to break the Land Speed Record again in 1932, setting the pace at 253.97mph, and then again in 1933 using a supercharged V12 engine to set a pace of 272.46mph. Now he was interested in cracking the 300 mph barrier. He tried first of all at Daytona. A new, all-enveloping body was made for Bluebird and on 7 March 1935, he set a new standard of 276.816mph, the biggest lesson being that Daytona had had its day regarding really high-speed attempts on the record.

The Salt Lakes of Utah were already beckoning with their promise of almost endless space and unusually good weather conditions. Thus it was that the whole centre of activity was to move to Bonneville, Utah. Camp bell set the seal on Bonneville's suitability in the autumn of 1937. Despite tire troubles, engine troubles and everything else, he recorded an official time of 301.129 mph. It was Campbell's ninth attempt on the Land Speed Record, it was also his last as he turned his eyes onto yet another frontier - water speed. With the departure of Campbell from the scene, George Eyston, a familiar figure in record-breaking circles, stepped into the vacuum left.

George Eyston's Thunderbolt

Although a class winner, Eyston had never gone for the big one. But above all else Eyston was a shrewd organiser and, when offered a sponsorship in 1937, accepted the brief and had a car built from design to completion in the astonishing time of six weeks. With the aid of a trained aerodynamicyst, Eyston produced a car which was powered by two supercharged Rolls-Royce Schneider Trophy engines giving him 4700hp to feed through the eight wheels of his Thunderbolt.

After trials in the USA and some tribulations with various 'parts of the car, his record breaking run came almost as a relief when, on 19 November 1937, he set an average of 312.oomph. Despite the gathering war clouds in Europe, interest was still as keen as ever, and the talented designer Reid Railton, BSc, AMIAE, was given almost carte blanche by Brooklands star John R. Cobb to build a new contender. What Railton produced was a design using two Napier Lion engines hung on a cranked frame to cut down frontal area, length and weight. With the engines producing 1250bhp at 3600rpm it was found that the most convenient way of getting the Railton Special started was by push-starting it but, even so, it was to prove effective as a piece of machinery.

As it was, both George Eyston and Cobb arrived at Bonneville at around the same time in 1938. Eyston started business straight away. After recording one run at 347.155 mph, it was found that the photo-electric cell of the timing device would not pick out his car clearly at the very high speeds he was achieving. A lick of black paint over Thunderbolt's sides soon cured that, however, and Eyston was able to gain a psychological advantage over Cobb by improving his own record to no less than 345-49mph. Unruffled, Cobb then went out and calmly set a new record of 350.20mph.

Even so, Eyston was not finished and after further work on the car he was back on the salt to set up a new record of 357.50 mph. With that final flurry of activity both camps packed up and departed back to Europe. Eyston, by 1939, had acknowledged that his Thunderbolt could not appreciably improve on its performance and tactfully withdrew from the duel but Cobb was full of confidence that a winter's work would yield the required result. By 23 August 1939, he was proved right. With the minimum of preliminaries and fuss he clocked an average of 369.74mph, and then the war came. In the light of what happened during the intervening period between 1939 and 1947, it seemed impossible that a new challenge could be mounted from Britain, but by the autumn the last successful piston-engined contender for the Land Speed Record was ready and waiting at Bonneville.

The Railton Special

The car was simply Cobb's Railton Special. After a multitude of troubles with things like carburation and camshafts, eventually the car was right and the track also. The result was a run of 385.645 mph one way and 403.135 mph the other, giving an average and a new Land Speed Record of 394.196 mph. It took a change in the type of motive power used to dislodge Cobb. And the trail leading up to a new Land Speed Record was littered with some brave and expensive efforts. Donald Campbell, Sir Malcolm's son, set off on a campaign using a turbine-powered Bluebird which was to bring him ultimate though qualified success.

Craig Breedlove's Spirit of America

In the eyes of the public, though, the next big break-through came when an American, Craig Breedlove, had the idea of fitting an ex-Services jet engine into a tri-wheeled frame and going for the record. Using 90% of the available power on one run and 95% on the second, he set a new average of 407.45 mph. Of course, there were howls of protest. The vehicle, called Spirit of America, was banned as being a tricycle, as not having a' reverse gear, as not having power fed through its wheels, etc. Nevertheless, to Joe Public and his wife, Breedlove held the record.

Donald Campbell persisted with his attempts to gain the real Land Speed Record. After some appalling luck and after having to bear the burden of some extremely unfair criticism, as well as having to recover from the effects of a very serious crash in Bluebird, he eventually achieved his desire with a speed of 403.10 mph. Although he had the official record, nothing could disguise the fact that a vehicle with its power fed through the wheels had little chance of ever again regaining the coveted Blue Riband of motor sport.

Wait Arfons Wingfoot Express

In America the combatants were, by this time, well along the jet-engined route to higher and higher speeds and the next serious challenger was another jet hybrid built by Wait Arfons and named the Wingfoot Express. After the almost mandatory teething troubles and other problems, the Wingfoot, in the hands of Tom Green, set a new mark of 413.20 mph on 2 October 1964. But Wait had a brother, Art Arfons, and brother Art had another jet hybrid, his revelling in the name of Green Monster. A crude, unsophisticated device, estimated to have cost a fraction of what others were spending, but which took untold hours in its construction, the Green Monster could do its stuff, with the net result that just three days after Wait Arfons had cracked the record, Art recorded an average of 434.03 mph, using only 60% of his available power.

Things were getting almost hysterical on the Salt Flats, though, as waiting in the wings was a redesigned Spirit of America fitted with a new engine capable of 5700lb of thrust. In an effortless programme, Breedlove posted a new fastest time of 468.72 mph on 13 October. Not content with that he was back on the salt by 15 October to record 526.28 mph average, even though he went out of control after the second run and ended up with his car in a nearby lake.

A Change To The Land Speed Record Rules

But still October had not finished and by the 27th Art Arfons was back, with the engine modified to give just a little extra power, just enough for him to crack through the traps at an average of 536.71 mph, to leave the world reeling after such an amazing month of record breaking. Even the FIA were forced to recognise that a new force was available in the sphere of Land Speed Record attempts. The confusion of having three different Land Speed Records lasted until December 11, 1964, when the FIA and FIM met in Paris and agreed to recognize as an absolute Land Speed Record the higher speed recorded by either body, by any vehicles running on wheels, whether wheel-driven or not, and accordingly, the rules were modified into two classes: one for cars with power fed through their wheels and the other for those that remained in touch with the ground no matter how they did it. Thus, Art Arfons' Green Monster was belatedly recognized as the absolute Land Speed Record holder, while Bluebird held the now-separate wheel-driven land speed record, and Spirit of America the tricycle record. Since then, no wheel-driven car has held the absolute record.

Surviving The 3½-mile Skid

Tom Green in the Wingfoot therefore had the honour of being the first officially recognised jet-powered holder of the Land Speed Record. By 1965, both Breedlove and Arfons were ready again. Breedlove with a redesigned Spirit now sub-named Sonic I was first out on the salt in November with 15000 Ib of thrust available from a J79 turbo-jet He smashed Arfon's last figure to post 555.48 mph. But Arfons was ready. Five days later, Art flashed over the course at an average of 576.553 mph and survived a 3½-mile skid when a tire burst.

The Summers Brothers Goldenrod

But the duel had not finished although time was taken out for a piston-powered vehicle, the Summers brothers Goldenrod, to have a crack at the Division Two record. Using four modified Chrysler V8 engines in a 32 ft long vehicle, the brothers were able to wipe out Camp bell's extremely expensively gained record and set a new standard at 409.277 mph. It was just an interlude in the serious business, though, and the Summers' achievement simply paled into insignificance three days later when Breedlove came out onto the salt and became the first man ever to break 600 mph recording 600.601 mph.

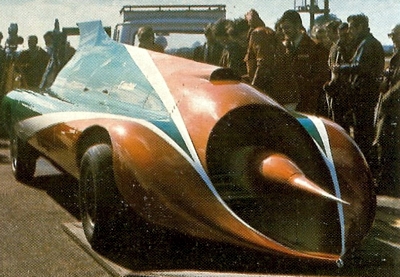

Gary Gabelich's Blue Flame

Even so, both Breedlove's and Arfon's vehicles were relatively crude in conception compared with the' next record contender. Although it did not make it to the Salt Flats until the autumn of 1970 the Blue Flame was a long time coming. The result was a vehicle that weighed in at 2 tons 19 cwt although only 6~ cwt of that was attributable to the engine. With a front track of 9 inches and a rear track of 7 ft, the Blue Flame was a purpose-built vehicle with only one aim in mind. Using a system whereby superheated steam and oxygen were passed over a heat exchanger to provide the basic of motive power, it is estimated that Blue Flame could produce the equivalent of 58,000 bhp for 20 seconds.

In the event, it was throttled back down to produce 13,000lb of thrust-a mere 35,000 bhp. So, on 23 October 1970, Blue Flame was wheeled out onto the salt flats and push-started to save fuel. On its first run, driven by Gary Gabelich, it recorded 617.602mph, on the second 627.287mph, to post an average for the mile of 622.407 mph and 630.388 mph for the kilometre. Unofficially, it is said that Blue Flame peaked at 650 mph - the age of the rocket car had arrived and with it problems regarding the sound barrier and the effects of sonic boom.

Also See:

Land Speed Record Drivers |

Land Speed Records (AUS Edition)