Joseph L. Hudson abd Roy D. Chapin

The men behind the Hudson Motor Car Company early in 1909 were president, Joseph L. Hudson, businessman, founder of a big Detroit department store, whose name was also used for the Motor Company presumably because his purse provided most of the initial capital; and Roy D. Chapin who had worked previously for Ransom E. Olds (who created the Oldsmobile and, later, the Reo) and gained personal fame some eight years before, in 1901, by driving a single-cylinder Curved Dash Runabout from Detroit to the New York Show as a reliability and endurance stunt.

Between Olds and Hudson, Chapin had helped to get the E. R. Thomas-Detroit Co off the ground, and its successor, the Chalmers-Detroit Co. However, the Hudson promotion was to monopolise his attentions until his death in 1936.

Howard Earl Coffin

Another businessman involved in the formation of Hudson was Howard Earl Coffin from Ohio, who had built a gas engine in 1897, a steam car two years later, and joined R. E. Olds in 1902. After becoming Chief Engineer there, he broke away to help Chapin launch the E. R. Thomas-Detroit and its Chalmers successor, and finally the Hudson.

By 1910, when vice-president of Hudson, he was President of the Society of Automobile Engineers and, in that capacity, did much to establish the standardisation of items like material specifications, to the great benefit of the industry as a whole.

Hugh Chalmers

Hugh Chalmers, vice-president of the National Cash Register Co, came on the motoring scene in 1907 by joining E. R. Thomas-Detroit and, in next to no time, had bought half the stock - hence the Chalmers-Detroit. This tie in led to Maxwell and Chrysler. Looking forward to 1954, that was the year of amalgamation with Nash and the start of the American Motors Corporation, thereby linking Hudson retrospectively with other makes such as Rambler, Jeffery, Ajax and LaFayette.

The Hudson Model 20

In June 1909, the Saturday Evening Post carried the first-ever advertisement for the new Hudson car and, on 3 July, the first example reached the end of the assembly line. It was called the Model 20, and conformed in every respect with the established US pattern for a low-to-medium-priced automobile in technical specification, appearance and body styles. Indeed, in retrospect, it may seem astonishing that so many engineers designed such similar products and yet were able to talk big business into backing them.

However, history has proved time and again that the unorthodox is unlikely to sell well even if It works well, unless there is sufficient confidence and material support to keep it afloat until the buying public has been won over - slight variations around a familiar theme are generally a better bet. Where the Hudson seems to have scored from the outset was in providing a healthy power output from a conventional engine and better than average performance through matching cylinder capacity to body style and weight.

1909 Hudson Model 20. The Roadster was an immediate success. The original price was $900, and the 20 was finished in maroon with black trim.

1909 Hudson Model 20. The Roadster was an immediate success. The original price was $900, and the 20 was finished in maroon with black trim.

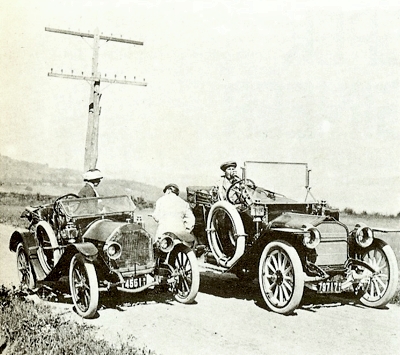

1910 Hudson Model 21, with four of the eight pioneers who founded the Hudson company. From left to right...R. B. Jackson, Frederick O. Bezner, Howard E. Coffin and Roy D. Chapin.

1910 Hudson Model 21, with four of the eight pioneers who founded the Hudson company. From left to right...R. B. Jackson, Frederick O. Bezner, Howard E. Coffin and Roy D. Chapin.

1911 Hudson's.

1911 Hudson's.

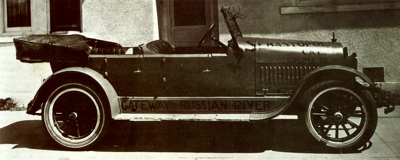

A Hudson Super Six. This is the actual car that was driven from New York to San Francisco and back again to prove its reliability. The outward journey took 5 days 3½ hours while the return trip took 5 days 17½ hours.

A Hudson Super Six. This is the actual car that was driven from New York to San Francisco and back again to prove its reliability. The outward journey took 5 days 3½ hours while the return trip took 5 days 17½ hours.

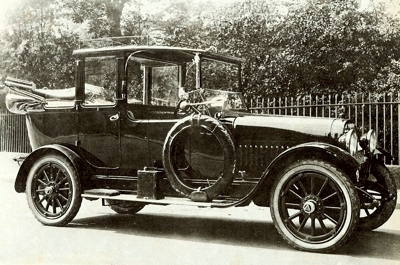

Another Hudson Super Six. Compared to the photo above, it shows how different the body styles were. This version is the 1921 Landaulette, which was favored by Presiden Hoover.

Another Hudson Super Six. Compared to the photo above, it shows how different the body styles were. This version is the 1921 Landaulette, which was favored by Presiden Hoover.

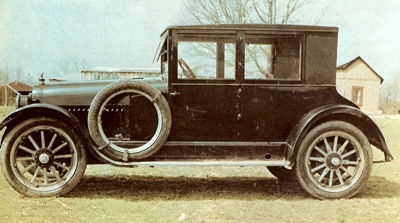

1922 Hudson Super Six Coach.

1922 Hudson Super Six Coach.

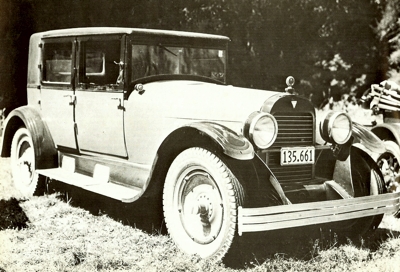

1925 Hudson Super Six four-door sedan.

1925 Hudson Super Six four-door sedan.

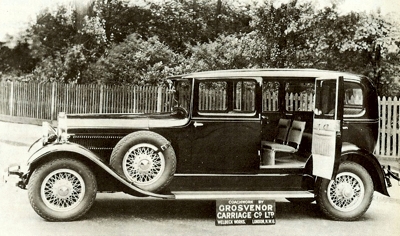

1929 Hudson Super Six, with bodywork by Grosvenor of London. Hudson were a prolific exporter.

1929 Hudson Super Six, with bodywork by Grosvenor of London. Hudson were a prolific exporter.

1939 Hudson six-cylinder business coupe.

1939 Hudson six-cylinder business coupe.

1946 Hudson Commodore Eight Sedan. The post-war Hudsons were basically 1942 models with minor front-end styling changes.

1946 Hudson Commodore Eight Sedan. The post-war Hudsons were basically 1942 models with minor front-end styling changes.

1951 Hudson Hornet.

1951 Hudson Hornet.

1951 Hudson Hornet.

1951 Hudson Hornet.

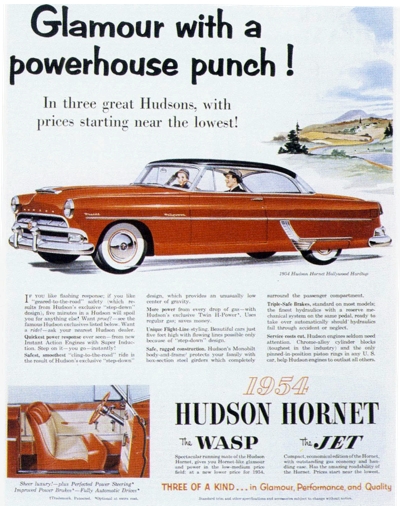

1954 Hudson Hornet.

1954 Hudson Hornet.

1954 Hudson Wasp and Jet.

1954 Hudson Wasp and Jet.

1954 Hudson Wasp and Jet.

1954 Hudson Wasp and Jet.

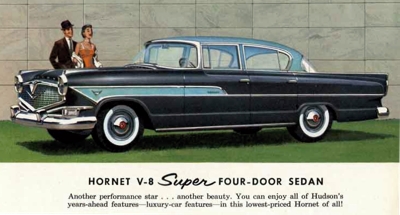

1957 Hudson Model 35787-2 V8.

1957 Hudson Model 35787-2 V8.

The last Hudson was the model 35787-2, completed on 25th June, 1957.

The last Hudson was the model 35787-2, completed on 25th June, 1957. |

And they tended more than most to stick to an established design, carrying forward outmoded features such as splash-lubricated big-end bearings and wet clutches long after these had been abandoned by other makers, but concealing them beneath visual ornament that changed to suit the times. So, Howard Coffin's Model 20 had a 20 bhp, four-cylinder mono bloc engine with side valves under an L-head. Bore and stroke was 3¾ x 3½ in, fired by an HT magneto, and it transmitted through a cone clutch and three-speed gearbox.

It had half-elliptic springs at each end and rode on non-detachable wood-spoked wheels. The two-seat roadster, with the option of a single bucket-type rumble seat or an extra large oval petrol tank behind the front seats, was claimed to reach 50 mph with a 3.5 to 1 final drive, a 4 to 1 ratio being optional for the heavier bodies. Four thousand Model 20s were sold that first season and, by the end of 1910, Hudson were rated seventeenth in the league of American car makers.

The Hudson Model Six-54

For 1911, the 20 was succeeded by the more-powerful Model 33, for which there were three body styles - Pony Tonneau, Roadster and Touring four-seater, the latter having step-over sides for the front seat, and doors only for the rear tonneau. That year, sales reached 6486. 1912 witnessed the death of J. L. Hudson and the birth of the first six-cylinder Hudson, the Model Six-54, a big and handsome machine with 6 liters and 54 bhp to propel it. Advertisements claimed a maximum speed of 65 mph for the car and the ability to reach 58 mph from rest in half a minute.

Standard equipment for the Six and the four-cylinder Model 37 (now with a 4-inch cylinder bore) included electric lighting, 'self-cranking', and even a clock and speedometer. The larger car, with a 127 in wheelbase, was offered with a range of open and closed bodies to seat from two to seven, and the 118 in wheelbase four-cylinder had up to five seats. The sales line this year was that these cars were 'the work of no fewer than 48 design engineers, some coming from France, Italy, Germany, England, Belgium and Austria. They had worked in 97 factories and had a hand in building 200,000 cars. Experiment has been eliminated. The errors due to lack of experience and lack of knowledge have been left out of these cars.'

A feature of the big Six was a four-speed transmission with geared-up or overdrive fourth, an arrangement that Rolls-Royce had tried with the first Silver Ghosts several years earlier, but soon abandoned because the plaintive whine of indirect gears in the normal cruising range was unacceptable. By 1914, when the 4-cylinder had become the Model 40 (40 bhp) by virtue of having the crankshaft stretched with 5¼ in. throws to bring it into line with the Six.

The World's Largest Manufacturer of Six Cylinder Cars

Hudson considered themselves the world's largest manufacturer of six-cylinder cars, and total sales reached a record 10,261; by 1915, they were up again to close on 13,000, obviously unaffected by the war in Europe. The following year was even more successful, with production doubled (25,772) through the introduction of an instant winner, the Super-Six, and adoption of a one-model policy. Thereafter, there was never to be another four-cylinder engine behind the famous red triangle badge, and the cylinder dimensions of the Super-Six were to remain unchanged right through to 1930, at 31 x 5 in (88.9 x 127 mm, 4739 cc).

Right from its initiation, the Super-Six was marketed with either sedan, cabriolet, town car or limousine bodywork in addition to the touring versions, some having wire-spoked wheels. To demonstrate its staying power and performance over a long distance, a Super-Six became the first car to make the double crossing of the North American continent against the clock - outward from New York to San Francisco in 5 days 3½ hours, and back again in 5 days 17½ hours.

A contemporary photograph shows a wire-wheeled touring car with four begoggled passengers looking (car and occupants) very travel-stained on a stony track in the Sierra Nevada. For a round trip of more than 7000 miles over every type of going - much of it unsurfaced and including mountain ranges and long tracts of desert - this was a remarkable feat by both men and machine. Five years earlier the record for the single east-west journey, achieved by a Reo, had been only six hours less than the Super-Six's double crossing, but in the interim there had been a lot of road-building.

By 1917 America had become embroiled directly in World War 1 and chief designer Howard Coffin's time was largely occupied with the US Board of Aeronautics, of which he was chairman. President Hoover had taken to a Super-Six landaulet and Hudson's output of almost 21,000 for the year included a large batch of military ambulances. Floyd Clymer's Catalog of 1918 Cars lists no fewer than ten body styles for the Super-Six, each with identical specification apart from wheel and tire dimensions, even the 125 in wheelbase being common to all.

Simplest and cheapest of the Hudson range was a Seven-Passenger Phaeton (open tourer) for $1950, and you could have bought two of those with a bit of change left over for the price of the Full Folding Landau ($4250). Between these extremes were the Four-Passenger Phaeton (more costly than the Seven-Passenger for some reason) at $2050, a Runabout Landau at $2350, a Four-Door Sedan at $2750, a Touring Limousine at $3150, a Limousine at $3400 and Limousine Landau for $3500, or Town Car for $3400, and a Limousine Landau or Town Car Landau for $3500.

The Essex Terraplane

In those days, the House color for Hudsons was blue, but there was a choice of blues - Coach-painter's, Hungarian or India; other finishes were also available. Limousine equipment included a heater for the rear compartment, footrests and pillows, a vanity case and courtesy lights. Wood-spoked artillery wheels with detachable rims were standard, with the option of centre-lock wire wheels and, in each case, the back wheels only were braked by contracting and expanding shoes sharing common drums, and actuated by the pedal and hand lever respectively.

At the Detroit Show for 1919 models, Hudson introduced a cheaper line under another name, as other major US companies were to do. This was the Essex, destined to turn full circle again in later years via the Essex Terraplane, then simply Terraplane and finally Hudson Terraplane. In the years 1919-32, some 1,331,000 Essex cars greatly expanded Hudson business and their sales in the peak years 1925-1929 greatly exceeded those of the parent company.

Through to the end of 1923, it had a 2.0-Iitre, four-cylinder engine with overhead inlet valves and side exhausts. One source credits it with 55 bhp, giving the car a top speed around 60 mph, but this seems scarcely likely when related to the Model A Ford of some years later, which drew only 40 bhp from 3.3 liters and could also reach 60 mph. However there have always been discrepancies between the brake-horsepowers developed in boardrooms and those actually provided for the customer to transmit to the road. Cylinder dimensions were 85.7 x 127 mm, cooling was by thermo-syphon, the big-end bearings were lubricated by splash, and a three-speed gearbox was engaged through the customary Hudson multiplate wet clutch.

Initially, the Essex carried three body styles - four-door sedan, five-passenger phaeton and roadster with rumble seat. Advertisements extolled its light weight, durability, rich appointments, low cost and economy, and boasted it was a 'tremendous performer'. 'The Essex's motor would inspire a whole season's advertising campaign,' they wrote. 'A slogan might be written about its beauty.' Indeed it might, like: 'Even the right-angles are wrong angles'. Not that it was any uglier than most US cars in that era of almost uniform sameness and drabness, before a brilliant nucleus of styling engineers, working first on their own account, had expanded their influence beyond the premises of the specialist coachbuilders.

Even in its first year, however, the Essex outsold its costlier stablemate 21,879 to 18,175. In its second year, the Essex pioneered a very significant option, a two-door body so inexpensive as to be within reach of humble buyers who had previously been denied closed coachwork. With its uncompromising boxy figure relieved only by a shapely posterior, it was not beautiful, but by 1925, 80% of Essex production was two-door coaches and other makers had had to follow suit.

The US Mail Orders A Large Fleet of Essex Phaetons

In 1920, a large fleet of Essex phaetons was ordered for rural deliveries of US mail and, to publicise this commercial jackpot, the company despatched four on transcontinental runs; one completed the classic San Francisco to New York marathon in 4 days 14 hours and 43 minutes. In that year, too, a specially equipped Essex phaeton was delivered to Edward, Prince of Wales. It quickly became a favorite in export markets and, in 1922, a Japanese hotel proprietor in Tokyo acquired a batch of 42. It is not known how many of these survived the great earthquake and devastating fires there in 1923, but a record of vehicles registered in that city soon after the disaster reveals that Essex were second only to the Model T Ford.

In 1924 came the first six-cylinder Essex which very soon supplanted the Rapid Four, as it was called. It had a side-valve engine of only 2.1 liters capacity, increased by three stages (in 1925, 1927 and 1929) to 2.6 liters, which final form carried it through to the end of the marque's existence three years later. After several lean years of post-war depression, the Hudson-Essex fortunes rose rapidly from 1923's 89,000-odd to almost 134,000 customers in 1924 and over 300,000 in 1929, of which about a third were Hudsons; after that, of course, the bricks of Wall Street suddenly crumbled away and things were never the same again for the Hudson Motor Car Company.

During this period, the Essex was given balloon tyres (1925) and front brakes (optional from 1927 and standardised the following season), a plated radiator shell in place of a painted one from 1926 and also, for 1927, this item was changed in form from pseudo-Rolls-Royce angular with horizontal shutters to the arched style of the Hudson. As a guide to its place in the industry, the cheapest US car in 1929 was the Ford 'A' roadster at a rock-bottom $385, and the cheapest sedan, on the same chassis, cost $495; next in succession came the Whippet coach at $535, Chevrolet and Durant at $595, Plymouth at $690 and Essex at $695.

The Hudson Super-Six

But for this article, lets return to the true Hudson, the Super-Six. It was in full swing in 1919, but we should look back two years earlier to this model's first competition success, when R. Mulford drove a stripped and tuned version to victory in a 150-mile race on a track at Omaha at an average of 101 mph; in 1919, another finished in ninth place in the Indianapolis 500 with Ira Vail at the wheel. Then, in 1927, the famous cigar-smoking

Barney Oldfield drove a two-door coach around the Culver City Speedway for a thousand miles at an overall average speed of 76 mph. It would have been powered by a new engine with the same cylinder dimensions (3½ x 5 in) but fitted with overhead inlet valves like the obsolete Essex Rapid Four.

After a three-year run, the inlet-over-exhaust layout was again abandoned in favour of the simple L-head side-valve and, from that time on, no Hudson engines were made with valves in the head, although a few of the last cars to bear the name had OHV engines by Packard and American Motors. In the peak year of 1929, Hudson-Essex combined rated third among America's best sellers, but this does not tell all the story because these cars were enjoying an exceptional popularity in overseas markets. For instance, more than 17% (about 40,000 cars) of the 1928 production went overseas, and this export prestige endured right through to the outbreak of war in 1939.

The next landmark was in 1930 when a straight-eight engine was introduced to supplement the six-cylinder, but replaced it the following year as the sole Hudson power plant. This was a neat piece of rationalisation in that it shared the cylinder bore and crankshaft stroke of the six-cylinder Essex, so that certain parts were interchangeable. The five-bearing unit received an increase in cylinder bore to 76 mm in 1932, bringing the swept volume to 4168 cc, and in that form it remained in production, still with its splash-fed big-ends, through to 1953, with successive increases in power output from 95 bhp at 3500 rpm to 128 at 4200.

Although there was little aesthetic glory in the Hudson Eight or its derivatives, the strictly conventional unit was undoubtedly one of the finest of its time. It gave a very good power output, with lively response and a healthy torque curve from very low revs. It was also silky smooth, easy to maintain and reliable over long periods. Moreover, the Hudson chassis was comparatively light so that the power/weight ratio was favourable. The proof of this is evident in the retention of the same engine for over twenty years within body shells that were changed many times, fundamentally or in details of decor, in the rat-race of the 1930s when Hudson were trying to recapture their earlier hold on the market now dominated by Ford, General Motors and Chrysler.

The Railton

When the lighter Terraplane range had the option of the straight-eight from 1933, it inspired the first and most famous of a new breed of Anglo-American sporting concoctions which became quite a vogue in the 1930s. This was the Railton, which earned itself a reputation out of proportion to the small numbers sold-only 1460 including 81 with six-cylinder engines -during the years 1933-39, plus a handful after the war. The Railton was sponsored by Sir Noel Macklin, who had previously been the driving force behind the all-British Invicta, and was assembled in the old Invicta works at Cobham in Surrey.

He engaged the services of Reid Railton, renowned designer of land-speed-record and track-racing cars who, in later years, emigrated to the USA and became a consultant engineer to Hudson. Railton modified the Terraplane chassis to improve its handling characteristics and bring it closer to the European concept of a sporting platform; he dropped the frame to lower the build, fitted Hartford friction dampers and raised the steering box ratio. A handsome radiator shell strongly remininiscent of the Invicta was complemented by a long bonnet with the earlier car's characteristic raised rivet heads along the hinges.

Considering the Railton's modest production output, the range of body styles offered was very ambitious. All were strictly British in appearance, emulating those of more expensive makes; for 1937, for instance, there were no fewer than three open tourers, three saloons, a coupe and convertible coupe on the shorter of alternative wheel bases, and a saloon, convertible and limousine on the long wheelbase. They were very lively performers with a maximum speed of around 90 mph, and a Light Sports Tourer with very spartan equipment, of which very few were made, was recorded at just over 100 mph, complemented by an acceleration time from zero to 60 mph of under 9 secs, which was sensational in those days. In 1938 a Railton took the sports-car record at the famous Shelsley Walsh hill-climb.

Hudson Production Halves

For Hudson, the 1930s were a turbulent period of fluctuating fortunes, profits and losses, with annual production dropping from around 114,000 in 1930 to only 41,000 in 1933; thereafter, rising progressively to over 123,000 in 1936 and falling again to 51,000 in 1938, in which year they suffered a trading loss of nearly $4.7 million. While Europe was at war, the output was up once more to 87,000 in 1940, with a loss of $1.5 million but, the following year, they were in the black again with $3½ million profit although fewer than 80,000 cars were sold.

In retrospect, the handsomest years from the styling viewpoint were perhaps 1930-1933, before the arrival of valanced wings, ever more elaborate radiator shells and all the other gimmicky additives planned to date earlier models and attract new custom. In July 1932, the brave American aviatrix Amelia Earhart went to Detroit to christen the first-off Essex Terraplane in the presence of Orville Wright and, later that year, one of these cars broke the stock-car record for the classic Pike's Peak hill-climb in Colorado.

Meanwhile, Hudson chief Roy D. Chapin was appointed Secretary of Commerce by President Hoover. Hudson fans also remember 1932 as the year the company built the only really unconventional cars in its long history; these were six eight-wheeled specials commissioned by the Japanese Government and used in the Manchurian war. They had four wheels at the back, two steered front wheels and two idler wheels just behind these, raised 'clear of the ground by a few inches so that they only contacted the ground over very rough terrain. The bodies were typical staff-car open tourers.

Axleflex Independent Front Suspension

In 1934, the Terraplane's 2.6-liter side-valve six, which developed about 75 bhp, was supplemented by a 3.5-liter six, which was later added to the Hudson range as an alternative to the eight. At about this time, there was a rather brief adoption of a curious form of independent front suspension named Axleflex. Each wheel was carried on a three-quarter length beam axle, giving it a swing-axle geometry, in conjunction with ordinary semi-elliptic springs. After a year or two, this was dropped in favour of a rigid beam axle located by radial torque arms, the springs being shackled at each end and relieved of all torque loads.

From 1934 to 1938, after the Essex name had been dropped, the Terraplane became almost indistinguishable from the top-line Hudson, sharing many of the body pressings as well as the 3½-liter, six-cylinder engine and, in 1939, the two 'makes' became one. For 1935, there was the option of an electric gear-shift- Electric Hand-in conjunction with a conventional three-speed box having a constant-mesh middle gear, and vacuum-operated clutch. This was the single-plate type with cork inserts and running in oil, which Hudson had adopted in 1929 and retained even through to the early 1950s for the 145 bhp 6-cylinder Hornet.

In February 1936, Roy D. Chapin died; his place was taken by A. E. Barit, who had been with the company since its inception and carried it through to the merger with Nash and formation of American Motors in 1954, whereupon he became a director of that combine. Bendix hydraulic brakes were adopted in 1936, replacing the Bendix self-wrapping mechanical variety - these were very effective when in good order with all the adjustments correctly set, but could be fiendishly wayward and unpredictable if anything was amiss. The new hydraulics were supported by a mechanical system which took over whenever they sprang a fluid leak.

The War Years

In the war years, from 1941, Hudson ran a plant, near Detroit, manufacturing anti-aircraft machine guns and sub-assemblies for aircraft, and stopped car production in February 1942 to devote all their resources to these and other military hardware - Helldiver folding wings, Airacobra cabins, engines for landing boats and many other items. The car assembly lines started rolling again in August 1945 with 1942 models, the front-end styling being rehashed for the following year's products.

Hudson Step-Down Design

A shortage of steel kept production below demand for a time but, in 1947, they were able to celebrate completion of the three-millionth Hudson made since 1909. For the 1948 model year, Hudson took their first really bold step forward into hitherto untrodden territory by bringing out an entirely new line with unitary construction of body and chassis, the innovation being that the frame enclosed the rear wheels. They called it their Step-Down Design, since the floor was considerably lower than the structural sills forming the side-members, and only the lower part of the back wheels was exposed to view.

Independent coil-spring front suspension was introduced for the new range. The old straight-eight 4168 cc engine, now developing 128bhp at 4200 rpm on a 6.5 to 1 compression ratio, was still the mainstay for the top quality models, but was now supplemented by a slightly larger, 4.3-liter, side-valve six giving 121 bhp at 4000 rpm. Appropriately, this was named the Super-Six. To take the place of the pre-war Terraplane, a lower-priced series, the Pacemaker, was added in 1949, with the same step-down body construction and 3.8-liter, 112 bhp, six-cylinder engine.

In the following year, the Hudson plant in Canada, set up in 1932, was again set in motion, and automatic transmission became optional for all the range. However, once again, the company was in financial trouble: following a post-war peak in 1949-50, when production had comfortably exceeded 140,000, with the books showing over $10 million profit for 1949, there was a rapid decline to 93,000 in 1951, 78,000 in 1953 and a loss of over $10 million, and right down to 32,000 in 1954.

The Hudson Hornet

Unfortunately, the Hornet failed to retrieve the situation despite wide publicity for its virtual supremacy in stock-car racing, and extravagant styling with annual chromium-plated face-lifts to keep the fashions changing. The Hornet engine was just over 5 liters (96.8x 114.3mm) and gave 145bhp at 3800 rpm, using a 7.2 compression ratio, and the claimed top speed of the sedan was 98-103 mph.

Early in 1953, yet another major effort to keep the company afloat materialised in the form of a compact light car, the Jet, with 3.3-liter six giving 104 bhp and wheelbase of only 105 in. There were Jets, Jet Liners and Super Jets, but they never really caught the public fancy. Meantime, the Pacemaker had given place to the Wasp and Super Wasp, the Hornet engine was boosted to 160 bhp and the faithful straight-eight was finally abandoned.

A special leather-trimmed coupe called the Hudson Italia, to be built in limited numbers with bodywork by Touring of Milan and powered by a 114 bhp Jet engine, appeared at the international motor shows; all to no avail, though, and after 1954, no more Hudsons left the Detroit factory. Resulting from the merger with Nash-Kelvinator, concluded in May 1954, Hudson production was transferred to Kenosha, Wisconsin, and the 1955 Wasps and Hornets were Nash-bodied with Hudson stings, apart from the Rambler compact which could sail under Hudson colours, if you wished, simply by a change of badges.

As mentioned earlier, the last of the Hornets were powered by first Packard and then AM V8 motors and, after 1957, they were at last allowed to fade away after being progressively stripped of all the individualistic character and respectability invested in them by Roy D. Chapin and his associates.