|

Rolls-Royce

|

1904 - Present |

Country: |

|

|

Charles Stewart Rolls and Claude Johnson

In the early days of the motorcar it was the wealthy and influential who had to be persuaded into buying them, something that could only effectively be undertaken by their peers. Thus in 1903 the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls ran several motor agencies, of which the most distinguished had originally been that of Panhard.

When Pahnard started to go into decline, Rolls was anxious to find a good British car to replace it, one good enough for him to associate his name with it, and add to the lustre of both. At that time, too, Claude Johnson was resigning the secretaryship of what would later be knwon in the UK as the Royal Automobile Club, in order to apply his administrative gifts to the promotion of the Rolls business, of which he was partner.

The Society of Gentlemen

Also at that time, there was a man whose unkempt appearance and coarse vocabulary would normally have disqualified him from the society of gentlemen, a man who had risen from an impoverished childhood to become an electrical engineer of distinction, and a man who was keen to make a really good car. This was Frederick Henry Royce, chief engineer and partner in F. H. Royce & Co. Ltd of Manchester, originally a backyard workshop making domestic bell sets but by the turn of the 20th century it was flourishing as a manufacturer of worldwide repute of electric cranes and dynamos.

It seems most historians agree that it was in 1902 that Royce begun to take an interest in motoring, buying a Decauville which, although better than many rival makes, still shocked him by the numerous engineering mistakes it embodied. Accordingly Royce concluded that he should make some cars himself, and his first was more or less an adaptation of that Decauville, a two-horsepower twin-cylinder affair that was completed and put on the road on All Fools' Day 1904.

Rolls Forms An Exclusive Agreement To Sell Royce Cars

It attracted widespread praise for its flexibility, quietness, reliability and refinement of running. The news of it reached Rolls by intermediaries who were able to effect an introduction, and Rolls visited Manchester: the result was an agreement that his company take all the cars made by Royce. Soon after, it was further agreed that they should be called Rolls-Royces, though it was not until 1906 that the company, Rolls-Royce Limited was formed.

Already Royce had advanced his plans for new versions of his car with three, four and even six cylinders, and Rolls enthused about the project, realising that this multiplicity of cylinders could only enhance the refinement of running already evident in the 10 hp Royce. Rolls also knew his customers well enough to appreciate that most car buyers could see a good deal more clearly than they could think, and he and Johnson together impressed upon Royce that a lot more spit and polish would be necessary to ensure a flawless external appearance.

The Principle of Entasis

By the end of 1905 all the new cars except the 30 hp six-cylinder were ready, though the 20 hp on show at Paris had a dummy engine, but no one noticed, amidst the acclaim for the beautiful finish of the cars and the superb appearance of the new Palladian radiator. Royce is supposed to have modelled this on the radiator shell of the defunct Norfolk car, but it must be credited to Royce himself. Only Royce was enough of a perfectionist to insist upon the radiator being fashioned in accordance with the principle of entasis (by which the ancient Greek architects overcame the distortion produced naturally by the human eye, by introducing a slight convexity to flat surfaces), despite the formidable manipulative problems that it created in manufacture.

Hindsight showed that he was right, and when in later years he wanted to abandon that radiator because it seemed to offend all established aerodynamic tenets, Johnson was adamant that a Rolls-Royce without that radiator was no Rolls-Royce, and that it should never be abandoned. One of the new engines intended to sit behind it was very soon abandoned: the three-cylinder had a production life of only six examples. There was nothing intrinsically wrong with it, but it did not fit into the rationalised production scheme in which cylinder blocks were cast for pairs of cylinders that could then be employed as building modules for engines of varying sizes.

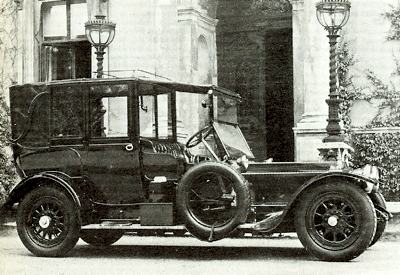

1909 Rolls-Royce 40/50 with coachwork by Hooper.

1909 Rolls-Royce 40/50 with coachwork by Hooper.

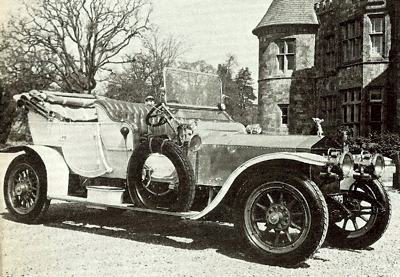

1910 Rolls-Royce six-cylinder Silver Ghost.

1910 Rolls-Royce six-cylinder Silver Ghost.

1911 Rolls-Royce, with the new and now famous mascot on the radiator grille.

1911 Rolls-Royce, with the new and now famous mascot on the radiator grille.

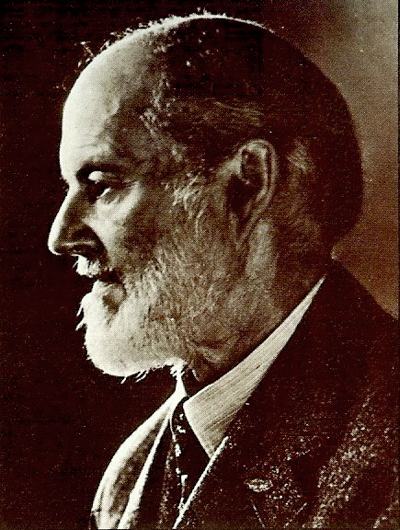

Frederick Henry Royce.

Frederick Henry Royce.

Charles Stewart Rolls

Charles Stewart Rolls

1911 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost roi-des Belges tourer, with coachwork by Baker.

1911 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost roi-des Belges tourer, with coachwork by Baker.

1911 Rolls-Royce 50/60.

1911 Rolls-Royce 50/60.

1912 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost six seater tourer.

1912 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost six seater tourer.

1914 Rolls-Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost with Speedy Roadster body.

1914 Rolls-Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost with Speedy Roadster body.

1914 Rolls-Royce 40/50, which would later become known as the Silver Ghost. It was produced between 1906 and 1925.

1914 Rolls-Royce 40/50, which would later become known as the Silver Ghost. It was produced between 1906 and 1925.

1920 Rolls-Royce Coupe de Ville.

1920 Rolls-Royce Coupe de Ville.

1914 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, with Landaulette coachwork.

1914 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, with Landaulette coachwork.

1926 Rolls-Royce Phantom I roadster, which was fitted with a 7.7 liter engine.

1926 Rolls-Royce Phantom I roadster, which was fitted with a 7.7 liter engine.

1926 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Landaulette, with coachwork by Hooper.

1926 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Landaulette, with coachwork by Hooper.

1927 Rolls-Royce Phantom I - this car was once owned by Greta Garbo.

1927 Rolls-Royce Phantom I - this car was once owned by Greta Garbo.

1932 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Coupe.

1932 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Coupe.

1923 Rolls-Royce Springfield USA Silver Ghost.

1923 Rolls-Royce Springfield USA Silver Ghost.

1930 Rolls-Royce Phantom II with Hooper body.

1930 Rolls-Royce Phantom II with Hooper body.

1932 Rolls-Royce 20/25 Convertible with coachwork by Barker.

1932 Rolls-Royce 20/25 Convertible with coachwork by Barker.

1934 Rolls-Royce Wraith Coupe de Ville.

1934 Rolls-Royce Wraith Coupe de Ville.

1934 Rolls-Royce 20/25, powered by a six-cylinder 4 liter engine.

1934 Rolls-Royce 20/25, powered by a six-cylinder 4 liter engine.

1938 Rolls Royce Phanton III Sedan de Ville.

1938 Rolls Royce Phanton III Sedan de Ville.

Rolls-Royce Coupe De Ville.

Rolls-Royce Coupe De Ville.

1938 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, with coachwork by Park Ward.

1938 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, with coachwork by Park Ward.

1958 Bentley S1 Continental Coupe.

1958 Bentley S1 Continental Coupe.

1973 Rolls-Royce Corniche convertible, powered by a 6700cc V8 derived from the Silver Shadow, and using coachwork by Mulliner-Park Ward.

1973 Rolls-Royce Corniche convertible, powered by a 6700cc V8 derived from the Silver Shadow, and using coachwork by Mulliner-Park Ward. |

The TT Rolls-Royce

The car that really caught the attention of the market was the four-cylinder 20 hp Rolls-Royce, demand for which exceeded production in 1905 and 1906 - though production amounted to only 40 cars. Anxious to press the Rolls-Royce reputation as high and as fast as he could, Rolls sought publicity in racing, persuading Royce to prepare two specially modified four-cylinder cars for the 1905 Tourist Trophy. This was an event for full touring-bodied cars, ballasted to the equivalent of four adult passengers, with a strict weight limit and a secretly prepared fuel consumption handicap, but it caused Royce no headaches. He had already introduced nickel steels for his axles and chassis, making it possible to build the cars considerably lighter than with the lower-strength materials used by rivals.

The advanced design of the Rolls-Royce carburetor, and the low mechanical losses consequent on careful manufacture and assembly, made the car naturally frugal. This TT Rolls-Royce, copiously lightened, with holes in the chassis frame and hubs, with wire-spoked wheels and somewhat filleted bodywork, was a superb car by the standards of its day, and Rolls soon showed in practice that it was the equal of anything else in the competition. Alas, his excitement got the better of him in the very first lap of the race, and he wrecked the gearbox before he had travelled a mile. Northey in the second car did the fastest lap of the day and finished a close second to the winning Arrol-Johnston. It was a good showing for so young a firm, and the good publicity it earned was of tremendous value, and even better this was followed by a win in the same event the following year.

Although Rolls was the keen racing motorist, Johnson was the man with the real flair for promotional activity, and he went campaigning with his favorite model, the six-cylinder 30 hp car, in the arduous Scottish reliability trials and other competitions of a similar nature. Instead of sticking with the established and successful models, Johnson was carried away by a couple of new ideas. One was his own, that Royce should design a luxury town carriage, whose engine was so self-effacing that it could neither be seen, felt, heard nor smelt, a sort of horseless carriage without the horse, and without any bonnet to indicate the presence of an engine.

Sir Alfred Harrnsworth

The other idea came from Sir Alfred Harrnsworth, who sought a Rolls-Royce which (in addition to all the good qualities already associated with the make) would also serve as custodian of the driver's conscience, being self-governing in such a way that it would be impossible for it to exceed the then legal limit which was 20 mph. Royce treated these two problems as one, solving them with a new 90° V8 engine with equal bore and stroke and a single-plane crankshaft, the displacement coming to just 3.5 liters. The two new cars bearing this engine did all that was required of them - except to succeed on the market.

This was probably the only mistake Johnson ever made, and he recovered from it quickly to carry on promoting his favorite 30 hp six. The car met a lot of rivalry from Napier in particular, but the greatest problem was within its own engine: the in-line six was always particularly susceptible to torsional vibration of the crankshaft, and the RR 30hp six was plagued by crankshaft failures because of it. Recognising that he was beaten Royce embarked on a completely new design. This car was to enjoy lasting fame, establishing Rolls-Royce beyond question as the setters of the very highest standards: it was the 40/50, and before long was called the Silver Ghost. It was Royce's masterpiece.

The Compulsive Perception of Imperfection

There was nothing superficially outstanding about the design, as Royce was not a deliberately innovative engineer; but there was in it an abundance of detailed perfection bearing witness to the fact that Royce was a gifted mechanic with an uncannily shrewd and perceptive technical brain. These detail felicities were backed by a quality control unique in the motorcar industry. It would be a mistake to deny Royce the ability to innovate, as his electrical engineering had already proved the contrary. His logical pursuit of engineering principles was sound enough, but the quality that made the name of Royce famous all around the world was something quite different, an intuitive and even compulsive perception of imperfection.

These standards were particularly necessary then. The poor roads, the mediocre fuels and lubricants, the lackadaisical metallurgy and crude workshop practice all combined to make the mechanical reliability of nearly all cars a matter more of statistical probability than of excellence of design. Most of all, the abysmal incompetence of most drivers made it necessary for a car to withstand regular punishment and mechanical cruelty.

The Superb 40/50 Rolls-Royce

The 40/50 Rolls-Royce was designed to survive this and more. Its chassis was broadly similar to that of the earlier 30 horsepower car, but the engine which gave it its title was completely new, the 40 being in round figures the horsepower according to the RAC piston area rating, the 50 in even rounder terms the actual output in brake horsepower, the product of seven liters running at a compression ratio of 3.2:1 and a brake mean effective pressure of somewhat less than 70 lb/in". It had two blocks of three cast-iron cylinders with integral heads and side-by-side valves (which could be changed by a trained chauffeur in four minutes, each car carrying a spare valve in a beautifully fitted wooden case).

These blocks were perched on a long aluminum alloy crankcase carrying seven main bearings for a crankshaft that, although devoid of balance weights, was robust by the standards of its time, and was distinguished by pressure feed of oil to its bearings through the hollow journals, as Royce had done in his V8 engine. It was in matters of detail that this engine excelled. The timing drive to camshaft and ignition was by gears, for Royce would have nothing to do with chains; the electrical apparatus was of outstanding quality, recalling the origins of the company; and all the minor controls were made with such loving care as to offer a tactile pleasure such as is only found in the work of the finest fitters and toolmakers.

An Early Form of Cruise Control

The governor system was another outstanding detail, widely criticised as unnecessary and extravagant, but appreciated by a few for the pleasure and assurance it could bring to driving. This centrifugal governor was interlinked with the accelerator pedal so as to supplement it but could also be overridden by it, and it was therefore quite different from the simple constant-speed governor associated with more primitive engines of the time. It could be used to maintain the car's road speed perfectly constant regardless of gradient, or to assist the driver in a gearchange that could be silent and smooth without any need for skilful co-ordination of feet and hands. This trick, taught by Rolls-Royce at their Drivers' School was the secret of the smooth progress achieved by most RR chauffeurs.

If the 40/50 was a car that forgave bad drivers, it was also one that stimulated good ones, and was soon being driven successfully in motoring competitions of all kinds, ranging from the Alpine Trials to long-distance record-breaking runs over such routes as Monte Carlo to London. It was Claude Johnson himself who set the pattern with the thirteenth 40/50 chassis, which had been fitted with a silver painted touring body on which all appropriate metal fittings were silver plated, while on the scuttle gleamed a cast name plate identifying this particular car as Silver Ghost. Thus was born that resplendent and revered name, eventually to identify the whole genus of Rolls-Royce 40/50 models from 1907 to 1925.

The Silver Ghost Trials

Johnson, with his flair for publicity, submitted the car to a 2,000 miles trial under RAC observation, taking in a drive from Bexhill to Glasgow using only direct third and overdrive fourth gears. The car was then dismantled and checked by an RAC engineer who could find nothing to criticise but a slight movement of the rings on one piston. After the Silver Ghost was reassembled it ran in the Scottish trial, and thereafter was driven to and fro between London and Glasgow, stopping only on Sundays, until it had completed 15,000 miles.

There was only one involuntary stop, quite early in the trial, when a loose petrol tap shook itself into the closed position; but otherwise the car ran like clockwork for 14,371 miles. It was then taken apart again, and this time there was slight wear found in some steering parts, and a need for re-packing the water pump. None of these conditions was serious enough to demand immediate attention, but Johnson insisted on the worn components being replaced- a nd when this was done the bill for parts was seen to be under UK£3 - amazingly low for the time.

While lusty enough to accelerate from 3 to 53 mph in third gear and go on to a top speed of 63mph, the two-ton car could average 17.8 miles per gallon (as it demonstrated during the trial); and having demonstrated that this supremely elegant, quiet and competent machine could be run economically, Rolls-Royce put the Silver Ghost into full production, beginning at the rate of four cars a week. They were to continue to build a total of 6,173 in the course of eighteen years, an average (including the years of the Great War) of better than seven a week.

Of course changes were made during this time, but not all of them were that good. In 1913 a normal direct-top four-speed gearbox replaced the three-speed affair, first in the so-called Continental model and later in the standard chassis. A team of three cars was entered in the 1913 Austrian Alpine Trial, backed by a privately entered fourth car, and they made mincemeat of the opposition, giving an almost perfect display of effortless superiority. Of course they were specially prepared, with aluminum alloy pistons and cantilevered half-elliptic rear springs as had been introduced on the London-to-Edinburgh cars.

The Napier Challenge

The London to Edinburgh affair grew out of a challenge issued by Napier in 1911. It involved a drive from London to Edinburgh in top gear, followed by a run at Brooklands, and including a fuel consumption test. The 55 horsepower Napier did 76.42 mph around the Brooklands track, and 19.35 miles per gallon; the Rolls-Royce, slightly modified, did 78.26 mph and 24.32 mpg. It was then stripped and fitted with a higher axle ratio and a narrow single-seat racing body, in which trim it was timed 101.8 mph over a quarter mile at Brooklands.

Carrying the King's Messenger

It was from the London to Edinburgh type, a few of which were offered for sale, that the Continental Silver Ghost was developed. This in turn became the standard model when peace came again after the great war of 1914-18. During that war the Silver Ghost served with distinction. Rolls-Royce chassis were reserved for the most glamorous or the most arduous duties, in recognition of their qualities. Because of its performance and reliability, it was a Rolls-Royce that sped over France at very high speeds carrying the King's Messenger. Because of the size, the ride quality, and the quietness of the Silver Ghost, it was often converted to serve as an ambulance.

Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Because of its capacity for taking punishment, it served as the basis of the most successful armoured car in the war, to be blessed later with a glamorous reputation spread by Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Despite the weight of armour and equipment being twice what the chassis was designed to carry, despite the need for the radiator to be masked with armoured shutters in action, in the tremendous heat of Libya, Arabia and Palestine, the 40/50 chassis proved incredibly reliable. Engine wear was slight, engine failure unheard of, and most of the running gear was equally dependable, apart from an occasional problem with hub bearings.

Rolls-Royce Aero Engines

The principle contribution of Rolls-Royce to the war effort, however, was not in the provision of durable motorcar chassis, but in the development of a new range of reliable aero-engines-something that Henry Royce was averse to, perhaps because of his association of flying with the death of Rolls, who was killed in a flying competition in 1910. The story of Rolls-Royce aero engines is a long one with which we cannot here be closely concerned. It is a story that brought the company immense fame and fortune, a story of engines that have enjoyed enormous and generally completely uncritical adulation.

But it is evident that most of these engines only became good after years of devoted and often frantic development work to eliminate the shortcomings of poor basic design. The finest example must be the most famous of all the engines, the Merlin, upon which so much was made to depend in the Second World War. Even if the adulation that were bandied about the Merlin during the Battle of Britain were largely forgivable propaganda, the Merlin was undeniably a great engine; but it took Rolls-Royce ten full years, from when they started on it in 1932, to get it right.

When the Vauxhall designer L. H. Pomeroy dismissed the Rolls-Royce car as 'representing the triumph of work manship over design', he was being not only unfair, but also inaccurate: the strength of Rolls-Royce lay always in their strong team of development engineers, and it would be much truer to say that their products put probation at a premium and design. Royce and his associates deliberately accepted the risk of such taunts, choosing to be cautious and conservative in everything they undertook.

Thus it was not until 1919 that the Silver Ghost acquired electric lighting and starting apparatus, not until November 1923 that it was given four-wheel brakes, augmented by a servo motor that had been adapted from the Hispano-Suiza example. Royce had been aware of the need for four-wheel brakes for a very long time before that; but, as was usually the case, the improvement was late in coming because a lot of time was necessary to ensure that the system was as good as it could be. Then, as to some extent now, the Rolls-Royce was made with an expensive disregard for any consideration that might prejudice its quality.

Finding the Flaws

For example, forgings were designed so that the grain flow of the finished machined product would be favourable, even if it meant that a brake drum weighing 32 Ib started as a forging weighing 106. Even more extreme was the connecting rod of the 40/50, finished at 2lb from a forging weighing 8, with only the perfect core of the forging remaining, and every bit of the rod's surface polished. Rolls-Royce claimed that every component of the car, when it was not machined, was filed and polished all over to find flaws or cracks in the metal, and every highly stressed piece was examined with a magnifying glass to discover surface cracks.

Flaw detection was in its infancy in those days, of course, and even twenty years later Rolls-Royce were somewhat behind the times in their detection methods. On the other hand they were ahead of their time in the measures they took to prevent flaws rather than tracing them: all holes bored in brackets and tubes were carefully machined to a smooth finish to avoid the possibility of any roughness starting a fracture, and the common practice of stamping the chassis number on one of the main frame members was shunned because the stamping might weaken the frame.

Rolls-Royce really were distrustful of other people's methods, and accordingly made everything possible themselves, even every nut. All steel parts were always rolled steel or forgings, except for four particular pieces which could only be cast; in every little detail, overt or covert, perfection was sought; and for those customers who could only see beauty on the surface, the nickel plating was of a quality unmatched by that of any other car manufacturer, simply because no other employed the Rolls-Royce technique. The commonly accepted system was electroplating, but Royce despised the microscopically thin layer this left, and instead had craftsmen cut pure nickel sheet to shape, and then solder it on to the part to be plated.

Quality Remembered Long After Price Is Forgotten

This was called close plating, and the finish kept its color permanently, did not scrape off, and had an almost indefinite life. The quality would still be appreciated, as Royce was so fond of remarking, long after the price had been forgotten. For a couple of years after the armistice in 1918 there were plenty of people prepared to pay handsomely for such work. Very soon the market became depressed, however, and Royce decided that something with a smaller engine would be needed. His original design for this, begun in 1919, was an in-line six of about 3½ liters graced by two overhead camshafts and disgraced by a skinny crankshaft that suggested the designers were no more capable than ever of mastering the problems of dynamic balance and torsional rigidity peculiar to a six-throw shaft.

In the long run it did not matter, as the Rolls-Royce

sales department were in such a hurry to get the Phantom 2 into production for the autumn of 1922 that the overhead-camshaft layout was abandoned due to a lack of development time, and with many other economies and deletions the 20 horsepower Rolls-Royce duly appeared on time. Almost the first thing the customers noticed was that instead of a separate four-speed gearbox it had a three-speed affair with a gear lever sprouting together with the handbrake lever from the centre of the floor.

This was immediately condemned as heresy if not (which was even worse) vulgarity, and in 1925 the company bowed before the storm and substituted a four-speeder with the levers to the right of the driver where they had always been in the past. Another feature of the design, less obvious to the average customer, was the adoption of Hotchkiss drive, presumably because it was so much cheaper and simpler than the torque tube axle location of the Silver Ghost.

The traction of the car did not suffer, as it was neither so light nor so powerful that this could ever be a problem, but the handling certainly did. Not that the customers were any more likely to drive the new small Rolls in a sporting manner, than they were to make free use of the four-speed gearbox they had so hypocritically demanded: all they wanted was to sit in a plush body behind a genuine Rolls-Royce radiator. The problem of the adipose body affected the 20 just as it did every other car that Rolls-Royce made, and it was one of the reasons why there would never again be such a long unbroken run for a single model as the Silver Ghost had enjoyed.

Johnson had been responsible for the one-model policy, and his judgement on that occasion had been perfect: it was by concentrating on the 40/50, and giving it a reputation that did not have to be compromised, that the company had been built into such a strong one. The introduction of the baby Rolls in 1922 made it clear that the future would be very different. The Silver Ghost by this time was suffering the same problems of increasing weight and diminishing performance, and a new engine had to be confected for it. It was not very different in capacity from that of the Ghost, though the pores were much smaller and the stroke much longer; but it had pushrod valve gear like that of the 20, and the consequent increase in power restored the performance of the car to more tolerable levels.

The New Phantom

With this new engine and other detail changes it was time for the name of the Silver Ghost to be dropped: its successor was named the New Phantom, and appeared a faster, taller, uglier and more ponderous version of its predecessor. In fact it enjoyed only a short life, going out of production in 1929, though it was quite a success here in the US where the Springfield factory had its best year in 1928, selling nearly 400 of this model.

The US venture started out in 1919, as a product of the Great War, during which plans had been made for the production of Rolls-Royce aero engines in America and a number of technicians had been here there from the Derby factory to supervise the training of workmen in Rolls-Royce methods. The armistice was celebrated before any American-built engine could go into active service, and it seemed a pity to Rolls-Royce that the organisation thus established, not to mention the goodwill, should be wasted.

The Death of Claude Johnson, and Rolls-Royce America Inc.

It seemed an even better idea that the vicious import tariffs be circumvented by the manufacture of the Silver Ghost in America, and the despatch of a further body of men to Massachusetts, bringing the total of Derby men there to 53, allowed the Silver Ghost to be put into production using exactly the same techniques and test methods as in England. For whatever reason, US customers treated the Springfield product as an imitation Rolls-Royce and wanted to buy British-made ones, not American ones, and sales progressively weakened. When the New Phantom's successor; the Phantom 2, came out in 1929 it was judged too complex an undertaking to be put into production at Springfield. By 1934 Rolls-Royce of America Inc died of bankruptcy, eight years after the death of Claude Johnson who had brought it to life.

The Rolls-Royce Continental

Changes made to the large Rolls and its baby brother in 1929 gave the two a great deal in common. The heavy rear axles were left to the mercies of simple half-elliptic springs and Hotchkiss drive; the gearboxes now had synchromesh available on third and top gears, there was centralised chassis lubrication. In many ways the cars were easier to drive than before. There was soon an extra version of the P2 known as the Continental, distinguished by its short wheelbase of only 12 ft instead of 12½. This chassis carried some of the most handsome bodies ever to grace any motor car; and when it was suitably bodied, the P2 Continental was capable of a genuine 90 mph or more.

Its performance came from a developed version of the original Phantom engine, now with a one-piece detachable light alloy cylinder head with cross-flow porting and greatly improved manifolding. Many felt that this engine lacked the smoothness of earlier Royce big sixes, but the car was still perfectly capable of dawdling along at 5 mph in top gear. Unfortunately, those customers who were genuinely interested in effortless high performance were being attracted by the new six-cylinder Bentleys, which were flexible, quieter than they used to be, and much faster than the Rolls-Royce.

When the 8-liter Bentley appeared in 1930, almost as quiet as a Rolls-Royce, just as impressive, and with tremendous performance, Rolls-Royce had cause for concern. They could perhaps comfort themselves with the knowledge that the Bentley Company was in dire financial straits, but by 1931 they had to consider the danger of Napier taking Bentley over. Since 1925 Napier had ceased to be a rival of Rolls-Royce, but now they were keen to get back into car production, and the acquisition of Bentley was the obvious way to go about it.

The British Central Equitable Trust

Plans were drawn up for Napier to buy the assets of the Bentley company, and put into production a developed version of the magnificent 8-liter, to be known as the Bentley-Napier; and it was not difficult to see what effect this might have on the future prosperity of Rolls-Royce. However, when all the negotiations had been completed, there remained the formal requirement of an appearance by both parties before the Receiver's Court, where the proposed arrangements might be given judicial approval so as to complete the winding up of the bankrupt Bentley company.

During the court hearing a strange lawyer rose and announced that he acted for the British Central Equitable Trust, and offered a larger sum for the assets of Bentley than Napier had proposed. Nobody present had ever heard of the British Central Equitable Trust. The whole manoeuvre was a surprise, perfectly timed and executed to leave Napier's counsel in a state of shock. A week later, W. O. Bentley learned that the mysterious intervention had been made on behalf of Rolls-Royce ; and a little later still he had it conveyed to him that since his service agreement with Bentley Motors was still in force, he was to be considered as part of the assets, together with the office furniture.

The Silent Sports Car

Finally he was told, which must have been most distressing of all, that Rolls-Royce had no intention of pursuing the development of his 8-liter car, or indeed any of his others. Instead, he was set to work by the hard-headed new Managing Director of Rolls-Royce, Arthur Sidgreaves, to produce a well-mannered sporting car derived from the 20/25 hp Rolls-Royce. The result was the 3½-liter Bentley, which those who could tell the difference between Cricklewood and Derby preferred to call the Rolls Bentley. It was a very good car, though in character it was neither Bentley nor Rolls-Royce; and it was hailed on the market in 1933 as 'the silent sports car'.

1933 was also the year in which Sir Henry Royce died. Almost immediately afterwards, Rolls-Royce badges were seen to bear black lettering instead of the customary red, and the legend grew that this was a sign of mourning for the founder. In fact the decision to change to black was made by Royce a month before his death, simply because the red had been seen to clash with the colours of some bodies, and it was felt that nothing about a Rolls-Royce should be inharmonious. Although the company insisted that the death of Royce made no difference to the product, the next big car, the Phantom 3 which appeared in 1936, was significantly different from anything that had gone before.

Inspiration from General Motors

For a start it had independent front suspension, fashioned after the manner of General Motors, a firm to whom Rolls-Royce had often looked for technical leads. Under the bonnet, now reaching higher and further forward than ever before, was a V12 engine that was dimensionally a pair of 20/25 blocks on a common crankcase and shaft. This made the capacity 7.34 liters, and the RAC rating 50.7 horsepower, but the net output was 165 bhp at 3,000 rpm, and later grew, with the adoption of four-port cylinder heads in 1938, to about 180.

As ever, the bmep and torque were extremely high at very Iow engine speeds, so that the Phantom 3 retained the top gear flexibility eagerly sought by drivers of the big cars. The engine had numerous detail refinements: the magneto had disappeared and now there were two separate coil ignition sets, the valves were all operated by a single camshaft mounted in the V of the crankcase through pushrods, rockers and zero-lash hydraulic tappets. The space liberated by the independent front suspension and the relatively short V engine made it possible for the wheelbase of the P3 to be 8 inches less than that of the P2 yet allowing more space for the passengers.

The proportions of the car undoubtedly made it imposing, but the established coachbuilders found it difficult to adapt their equally established styles to this change of proportion, and many of the bodies which clothed the P3 looked ungainly. A further subtle change was wrought by the reduction in wheel diameter to 18 inches, whereas the P2 had wheels of 20 or 19 inches diameter. Even discounting the sycophantic flattery that any Rolls-Royce was guaranteed, the P3 was one of the most outstanding luxury cars of its time, and a very impressive performer. If not impossibly bodied, it would do 95 mph; later cars would do a genuine 100, and the last 30 or so, with their overdrive gearing, were even faster.

More to the point was the acceleration: from standstill to 60 mph in 16 seconds was truly formidable by contemporary standards, and perhaps even more important was that the acceleration in top gear from 20 to 40 was quicker than from 30 to 50 - and from 10 to 30 it was quicker still! For those who were not afraid to use what was really a very sweet gearbox, there was now synchromesh on all except bottom gear, and the right-hand lever was in just the right place, alongside the driver's seat, instead of being up ahead of his knee, as in earlier cars. This was because the gearbox was again separate from the engine, not only to improve weight distribution a little, but also to allow a particularly massive cruciform cross-member to be set well forward on the chassis, so that its crux came between the gearbox and the engine.

Not long after the P3 was introduced Rolls-Royce anounced another new model, the descendant of the original baby 20. The engine had been bored out again to give it a capacity of 4½ liters and thus the 20/25 became the 25/30, an exquisite car that was beautifully balanced, sensibly dimensioned, and adequately fast. Their small car had always been slower than any Rolls-Royce should be, a want of power being aggravated by an excess of bodywork; the 25/30 certainly had no excess of power, but was fast enough not to be a source of embarrassment, and if not over-bodied would do a genuine 80. The same applied to the 4½ liter Bentley which was its sporting equivalent; the 3½ liter Bentley had been a very good car when bodied in a light and sporting style, but it was very seldom that such justice was done to it, and the extra engine capacity helped to restore some of the performance that was lost as bodywork became more and more gross.

As with the Rolls-Royces, the Bentleys progressed in a vicious circle, getting heavier and heavier as they grew bigger and more powerful, until there were few examples that could really demonstrate the superb handling, the lively performance, and the impeccable manners of what was potentially the most accomplished and meticulously made sporting tourer then on the market. At least the 4½ Bentley did last for three years. Alas, the 25/30, one of the nicest Rolls-Royce models of all, endured for only two, before giving way to modernism in the shape of the Wraith which was tantamount to a 25/30 engine in a scaled-down P3 chassis, welded instead of being put together with fitted tapered bolts in reamed holes as had been the traditional Derby manner.

The Scalded Cat

The Wraith looked as ungainly as the P3, but it remained in production for only a year, in which 491 were made (a figure which indicates the commercial strength of the company) before the war gave Rolls-Royce other things to do. Oddly, Bentley production continued a little longer, until 1941 in fact, to allow the completion of nearly twenty examples of the Mk 5 Bentley which was a sort of sporting Wraith with overdrive gearbox, 15 inch wheels and (usually) a handsome saloon body by Park Ward. Some other oddities and specials were produced during the war too, such as the notorious Scalded Cat - a car fitted with one of the first of the B series military engines, with overhead inlet and side exhaust valves, a straight 8 that pulled it up Porlock Hill in the UK in top gear. It was perhaps a rather low top gear, since the car's maximum speed was only 101.5 mph.

Big Bertha

The same engine powered a limousine prototype called Big Bertha which led to a small production run of the Phantom 4 after the war, built only for very special customers such as the Royal Family. Rolls-Royce worked immensely hard and to good purpose throughout World War 2, but the early post-war period presented a far from favourable situation in which to pick up the traces of the car manufacturing business. Taxation, petrol rationing, and material shortages of every kind made it clear that there was no place for such outside extravagances as the Phantom 3. Some sort of design compromise was called for: giant cars were out of the question, but a small one however practical could not be a real Rolls-Royce.

Dr. Llewellyn Smith and Lord Hives

In the pre-war Wraith and Bentley Mk 5, the Car Division, now under Dr. Llewellyn Smith, with Lord Hives in the Chair, sought and found their inspiration. Some things would have to be changed, as cars that were to be sold overseas could not be bodied by traditional coach-building techniques. Already in the late pre-war years, the assimilation of Park Ward had been a step towards standardisation of bodies, and now Rolls-Royce went a step further, and produced a design for the new Bentley, the Mk 6 that would be stamped out in quantities by the Pressed Steel Company, along with all the refrigerators and Morris 10s and amoung other things then being mass-produced.

The poor quality of available materials was a problem that could not be wholly overcome, but the long term consequences of it could hardly be foreseen at the time. The engine had to be changed, as it was impossible to enlarge the valves and ports any more in the pre-war six-cylinder engine, but the B series seemed a promising substitute. In its military versions, it was in four, six, and eight-cylinder variants with iron or aluminum blocks, but for car production the simple iron six was adopted almost as a foregone conclusion. It had a lot of early failings, with its bypass oil filtration, chromium plated cylinder bores, and pistons prone to seizure, but after a couple of years earnest work - and even the eventual grudging acquisition of a dynamic crankshaft balancer, long used by certain oftheir rivals - this large engine became reliable and powerful.

The Mk 6 Bentley

The electrical ancillaries were now bought out - but it was forty years since the birth of the Silver Ghost, 13 since the death of Royce, and the company was no longer beset by any self-imposed standards that it could now argue were irrelevant. Thus the riveting and bolting of the chassis was extensively replaced by welding, the centre-lock wheels were replaced by crude multiple-stud affairs, the water pump and dynamo were driven by a belt instead of gears. Once upon a time everything had been inspected, and each new car was road tested over about 350 miles, completely dismantled, checked, reassembled, and given a final trial run before body finishing; now, inspection was on a batch basis and 150 miles of testing was deemed sufficient.

The Silver Dawn

So the Mk 6 Bentley was not entirely faultless when it appeared in 1946 as a brave effort in a drab new world. Nearly silent it might have been, but it was less of a sports car than any earlier Bentley, its heavy flywheel and soft valve timing being strictly in the Rolls-Royce tradition. With an even milder camshaft and only one carburetor, the Rolls-Royce equivalent, the Silver Wraith, was downright leisurely, but for its intended market this was no impediment: when it went into production in 1947 it was as a chassis for attention by one of the few remaining specialist coachbuilders. This virtually disqualified it from export, so in 1949 the Silver Dawn was added to the catalogue, virtually a Mk 6 Bentley with a Rolls-Royce radiator on the front of its standard steel body.

The Silver Dawn stayed in the catalogues until 1955, the Silver Wraith until 1959, both of them being altered during their lifetimes. The changes were given more publicity in the Bentley context. The first was to increase the cylinder bore in 1951, raising the capacity from 4257 to 4566 cc in response to demands for more performance. It was the only alternative to raising the compression ratio, which the engine would not tolerate; and with this emendation the car became known as the Big Bore - which it very probably was. A year later it got the Big Boot and an optional automatic transmission, whereby the Mk 6 was promoted to become the R-type Bentley.

The R-Type Continental

Another model of outstanding beauty and exceptional merit was also developed from it, the R-Type Continental. With its engine bored out even more to embrace almost 4.9 liters, with a gearbox of beautifully close and high ratios, and with a streamlined aluminum-panelled body of imposing elegance, it was a beautiful and fast car, just what a Bentley should be. It would do nearly 120 mph, and could just exceed 100 in third gear, with handling that was reasonably good in the dry, though it wore its tyres out at a phenomenal rate if driven hard. In the wet it was best driven very gently - which, inevitably most customers did as a rule. A man with good hands, a heavy foot and a deep pocket would probably take his custom elsewhere, while the men who bought Bentleys were not impressed by the fact that the Continental weighed a quarter of a ton less than the standard R-type, but rather by the fact that its accommodation was less spacious. Only 207 Continentals were made, all but 16 of them with that superb body by H. J. Mulliner; and then it was time in 1955 for a new model to replace the R type.

The Bentley S-Type and Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud

With all the special knowledge gleaned from their engineering in the aviation industry, Rolls-Royce were expected to produce something outstanding. Instead they produced the S-type Bentley, and the Silver Cloud Rolls-Royce, identical except for their radiators. The propaganda machine explained this by saying that a Bentley owner was entitled to expect just as much quietness and refinement in his car as he might find in a Rolls-Royce, while no new Rolls-Royce could be deemed satisfactory unless it were just as fast as a Bentley! That was not very fast: with the 4.9-liter six and automatic transmission in a heavy ill-handling body the car hit its limiting headwind at about 105 mph; and if its two tons were pressed along like this for long, its 18 gallon tank gave it at best around 12 miles per gallon.

There was in fact an optional large tank, just as there was an optional synchromesh gearbox for the S-type Continental that was brought out in 1956, but neither option was much exercised, and the S Continental was a disgrace to an honoured tradition. The customers wanted opulence, but they also wanted ostentatious acceleration from standstill, so a new engine was summoned. Designed in an essentially US style, the new pushrod V8 mustered 6.23 liters and gave the S2 Bentley and Silver Cloud 2 RR much improved performance. Automatic transmission was now the rule, and though the first and second gears were so low as to be almost indistinguishable they ensured a rapid take-off (the car could reach 60 mph in 10 seconds); and although third ran out at about 72, the top-gear urge was enough to bring 100 up in about 35 seconds (the S1 took 50) and carry on to a maximum of 117.

Even the Phantom 5, with the same engine in an outsize chassis for the carriage-building trade, could reach a serene 100 or so. With the new engine came new bodily refinements, extra weight, and the need for power steering such as had been made optional on the S1. It had little feel and was left deliberately low-geared, RR invoking what they called the 'sneeze factor' and arguing that high-geared steering was dangerous since a quick movement of the wheel at high speeds might lead to the car actually going where it was directed. It was a telling summary of the typical RR customer's driving. What worried many people more was that this enormous car still relied on drum brakes. RR said that when they found a disc brake that was as safe, as powerful, as consistent and as quiet as their drum, they would use it; and they .reminded the public that 'Rolls-Royce brakes do not fade'.

The Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow

This was true: rather the old friction-driven servo motor faded first! Everybody knew that Rolls-Royce had something more modern on the stocks. They had to have, and when the S3 appeared with quadruple headlamps but otherwise the same specification it was recognised as a mere stop-gap. Then at last, in 1965, the Silver Shadow (the T series, in Bentley parlance) appeared - and created the biggest furore since the 'baby' 20 hp car. Criticisms flew, snap judgments crackled from every newspaper: this was something of national concern - the first modem Rolls-Royce since the Tourist Trophy model. The chassis had gone. The new car was of unitary construction, the hull stiff enough to carry independent suspension of all four wheels.

At the rear, self-levelling by high-pressure hydraulics under licence from Citroen did much more than keep the car on an even keel: it postulated an hydraulic system that could also deal with a braking system of unrivalled complexity, and so the old drums and friction servo vanished at last. With two power-assisted independent circuits supplemented by one direct line, plus the mechanical handbrake, a total of four separate systematic failures would be necessary before the car might be left brakeless. Somehow the fact that RR had at last adopted discs seemed relatively trivial. The company had adopted a number of other up-to-date ideas too, all of them appropriate to the new production-line style in which the Shadow was being given substance.

Before long the fast-wearing bias-ply tyres could be supplanted by 205-15 radials, the suspension being modified to accept them. The four-speed automatic gearbox with simple Fottinger fluid coupling was replaced by a three-speed box linked to the V8 by a converter coupling. Full control over the transmission could be exercised by the driver using a wand-like lever beneath the steering wheel: it was a delight to use, every flick being translated by electric motors into a perfectly smooth change. Though still a little intimidating by virtue of its size and the slowness of the steering, the Shadow allowed more realistic high-speed driving than any RR before. It had the roadholding to make such driving possible, and the structural integrity to make it safe.

The structure was theoretically a simple stressed-skin monocoque hull, but it went some way towards chassis theories by having resiliently-mounted subframes at each end from which to hang the suspension, running gear and power pack. In effect there were two halves to the chassis, held together by the body. The suspension was very soft on the early Shadows, and several reports went around of Royces that had rolled. The rear was soon made firmer, and then the car was astonishingly forgiving: put too hard into a corner, it would scrub away speed until it was safe, looking after its proprietor in a way that was almost uncanny.

The Rolls-Royce Corniche

Still, customers who wanted to drive like that would soon be able to have a high-performance Rolls-Royce: in 1971, with an engine enlarged to 6.75 liters, with higher-geared steering (even a smaller hand-wheel), greater roll stiffness, anti-drive and anti-squat suspension geometry, radial tyres, and even a rev-counter, the 123 mph Corniche took its place at the top of the catalogue. But by 1971 the company was in trouble; and there were plenty calling on the British government to save Rolls-Royce. It was the aero-engine side of the business that had run into difficulties with one of the new range of advanced-technology turbofans (the RB211) and could not keep to its contractual undertakings with Lockheed, whose new airliner depended on them.

Rolls-Royce had been making a killing for years in the aviation world, getting governmental backing for many new undertakings, being given the rest of the British aero-engine industry on a plate. The company could boast that every minute, somewhere in the world, an aircraft powered by Rolls-Royce took off; but they could no longer boast that the best rival jets in the world were copies of their own made under licence. In fact most of them had been copies of Bristol designs, but RR now claimed everything Bristol as their own; and in fact most of the great rival engines were now original designs by US and Russian firms who had snatched the lead.

In 1973 the motor car business was spun off as a separate entity, Rolls-Royce Motors. The main business of aircraft and marine engines remained in public ownership until 1987, when it was privatised as Rolls-Royce PLC, one of many privatisations of the Thatcher government.