|

Porsche

|

1930 - Present |

Country: |

|

|

The 1935 Berlin Motor Show

The Berlin motor show of 1935 was opened with a speech from Adolf Hitler with the statement, "I am pleased that due to the capabilities of the brilliant designer Porsche and his staff, it has become possible to complete the first designs of the German Volkswagen." This is one instance where Hitler was correct, Porsche was brilliant.

Porsche was widely recognised as an engineer of great ability based on his contributions to the world of motoring, yet his only his formal qualifications derived from part-time studies begun at the age of eighteen at the Technical University of Vienna. If his academic background seemed sketchy it was many years before the Stuttgart Technical College recognised his Austrian schooling.

Few denied his role in the development of the motor car and aeroplane engine, in agricultural tractors and many other related areas. So far as Porsche's work in automobiles was concerned there is evidence to suggest that he was emphatically not a chassis man, nor was he concerned with body design, but it is reasonable to consider him an artist in his own particular medium.

His detractors used to maintain that the man could scarcely draw a line and yet, as the governor of a busy independent design office (set up in 1930 after he had finished with Daimler-Benz) he could guide his draughtsmen's interpretations of his directions so that what was created was bursting with artistic conviction. When at his busiest, his principal tools were a formidable brain and some fearsome invective, as he was the antithesis of the intellectual highbrow. And despite the length of his career, his tremendous output testifies to the frequency of those occasions when he was extremely busy.

There is a great deal of continuity to be seen in his work - the swing-axle rear suspension, the teardrop streamlined body and engines designed deliberately to be relatively large and slow-running, lightly stressed and reliable. It is easy to see him as a man obsessed with fixed ideas. The Auto-Union Grand Prix car built for the 750kg Formula of the mid-1930's, the prototype peoples' car of Zundapp and NSU, the Volkswagen and the post-war Porsche 36 (which was not strictly his design but which grew out of a car that was) are all fundamentally similar.

An Obsession for Electricity

There have, of course been other designers obsessed with a principle, a singular notion that they have carried through to a repetitive realisation, but Porsche was really one of those creative men whose vision penetrated the reactionary barriers of more than the just the motor industry. After all, he started off in his youth (he was born in 1875) with an obsession for electricity, pursued despite furious opposition of his tinsmith father, until it carried him to the creation of an all-electric transmission system. This relied on electric motors set in the hubs of each wheel, and was first propounded for cars made by Lohner with whom he worked for six years at the start of his career.

Once Porsche had taken the first step of introducing a petrol engine to generate the electricity of the motors, rather than rely upon the hopelessly inadequate accumulators he was soon applying the mixed transmission system to machines of much more extraordinary specification. In World War 1 he built fantastic military trains of linked self-steering electrically propelled carriages, all deriving their motive flux from the dynamo car that led them upwards and downwards, around corners, over Alps, or even across bridges too flimsy to bear the weight of the whole train.

The Tiger Tank and Maus

A magnified version gave self-propelled mobility to the biggest artillery piece ever to travel by road, an enormous Skoda mortar firing 1-ton shells from its 26-ton barrel. In World War 2, the same mixed drive distinguished some versions of that most famous of Panzerwagen, the Tiger Tank, and was also incorporated in the design of that supertank born of Hitler's wild imagination, the legendary Maus. Between the wars, he dabbled in many other things, including helicopters and an inverted V12 engine that became the Daimler-Benz 600 series, acknowledged by at least one rival manufacturer as the best designed aero-engine to see service in the Second World War. There were agricultural tractors, too, together with all their hydraulic and mechanical appurtenances.

Better still from the point of view of income (and even more significant from the standpoint of other designers, once the patents ran out in 1950) there was the use of torsion bars as springing media in place of the leaf and coil springs that had formerly been the rule. His output was distinguished both for its quality and its variety. Even within the confines of the motor industry, Porsche was a man who went to extremes: during the latter part of his working life, his name was always associated with rear-engined cars, yet he was the creator of the first front-wheel-drive car, the original Lohner electric Chaise of 1900.

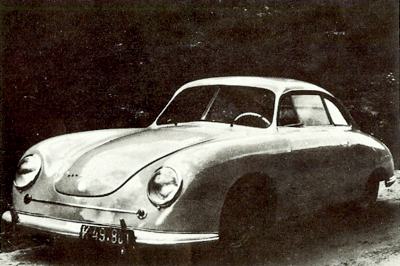

1948 Porsche 356 Coupe.

1948 Porsche 356 Coupe.

1959 Porsche Formula Two, fitted with a 4 cylinder 1500cc 170 bhp engine.

1959 Porsche Formula Two, fitted with a 4 cylinder 1500cc 170 bhp engine.

1961 Porsche RS60 1600cc Spyder.

1961 Porsche RS60 1600cc Spyder.

Porsche 356SC cutaway, used by Porsche for demonstration at motor shows during 1963.

Porsche 356SC cutaway, used by Porsche for demonstration at motor shows during 1963.

1966 Porsche Carrera 2000cc Six - designed for long-distance events.

1960 Porsche Carrera-Abarth.

1960 Porsche Carrera-Abarth.

1962 Porsche flat-8 1500cc Formula One.

1962 Porsche flat-8 1500cc Formula One.

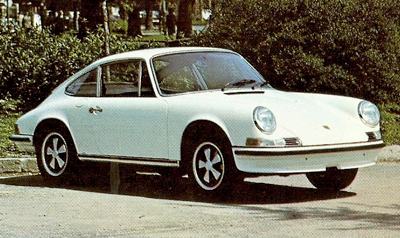

1964 Porsche 911.

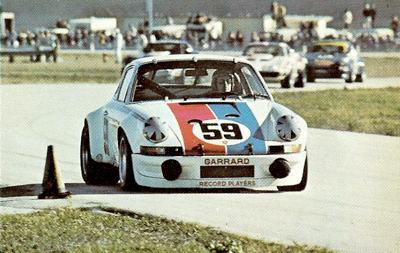

Porsche 911 Carrera on the track.

1971 Porsche 911S 2.4 liter.

Porsche 911S Targa.

Porsche 911S Targa.

VW-Porsche 914 in action at Monza in 1973.

VW-Porsche 914 in action at Monza in 1973.

Porsche 936 in action at the 1977 Le Mans, with Jacky Ickx at the wheel.

Porsche 936 in action at the 1977 Le Mans, with Jacky Ickx at the wheel.

1976 Porsche 935 - invincible in the World Championship of Makes.

1976 Porsche 935 - invincible in the World Championship of Makes. |

Austro-Daimler

For all his success with Lohner, Porsche felt himself confined in that relatively small factory, and at the age of 30 left to join the Austrian-Daimler company which later became known as Austro-Daimler. There he designed an 85 horsepower racing car, and a 30 horse-power tourer known as the Maja - named after Jellinek's other daughter (of course we all know his firstborn Mercedes gave her name to the car that Maybach designed for Daimler in Stuttgart).

The racing car had petrol/electric mixed drive, but Porsche could offer his new employers more ideas than they could deduce from the old ones: he designed aero- engines for airships, a form of water cooling for brakes, and an aeroplane engine with overhead valves looking significantly like that of a Volkswagen Beetle. He produced rotary engines, V engines and a broad-arrow engine. Most significant of all, he produced a new Austro-Daimler for the Prince Henry Trials of 1910, a car that with an engine of only four liters appeared unlikely to be competitive with the giants entered for the race by other manufacturers, but which thanks to its efficiency, light weight and low drag, performed extraordinarily well.

The Austro-Daimler Sascha

At this time, most of Porsche's thinking was aligned with the market for very big cars, but by the end of the war, he was experimenting with small ones, soon to be encouraged by the development he noted among mass- producers such as Austin and Citroen. In 1921, he designed his first small car, although Austro-Daimler were not terribly keen on the proposition, but eventually they compromised, and the car was marketed the following year under the name Sascha. Its engine was an in-line four with an overhead camshaft, its power approached 50 bhp, and the car was timed at a speed of 89 mph - a respectable rate now, and an extraordinary one then for a road-going car of only 1100cc displacement.

Three Saschas were entered in the 1922

Targa Florio and two of them won the appropriate capacity class, while the third was bored out to compete with the big racing cars and finished 7th among them, driven by Alfred Neubauer. Although he started well, Austro-Daimler did not, so Porsche left them in 1923 to become technical director of Daimler at Stuttgart. Considering the advanced designs for which he became renowned in later years, the remarkable thing about Porsche's stay with Daimler (later Daimler-Benz) was the extreme conservatism of everything he did.

Some of the things he did left a great deal to be desired, an example being the blown straight-eight two-liter Mercedes he built when he first went there, following the success of the blown two-liter four that he inherited on his arrival. The eight behaved atrociously, even though it was very powerful and fast, its roadholding was unreliable. He scrapped Paul Daimler's straight-six and substituted a bigger and more powerful engine of his own for the new S series Mercedes-Benz in the late 1920s, he produced what was basically a superb engine, and then he spoiled it by making wrong decisions about the cylinder head design and material, which led to condign limitations being imposed upon the use of the supercharger.

Karl Rabe

There are two reasons that explain the conservatism and the mistakes. One is that the other directors at Stuttgart were too cultivated, too successful and too rich, to have any technical wool pulled over their eyes by the unpolished Austrian upstart who was given to bad language and taken by the idea of tiny motor cars. The other reason is that Porsche had left behind him at Austro-Daimler the brilliant young engineer who had become his special protégé there, Karl Rabe.

All the evidence suggests that Porsche was no great shakes as a theoretician: very often the difficult bits (the original detail specification for the Auto-Union, for example) were done by Rabe, a man scarcely known for his own ideas, but whose eventual claim to fame was that he made so many of Porsche's ideas work. It was Rabe who took one of Porsche's designs and turned it into the potent but manageable hill-climb sprinter that made Hans von Stuck the 'king of the mountains'.

The Steyr Austria

Eventually, Rabe and Porsche were to be re-united .... At the end of 1928, it became apparent to Porsche that Daimler-Benz thought that they could get along without him, so at the beginning of 1929 he returned to Austria where he became chief engineer for Steyr. By this time, they were Austria's biggest car makers and stern rivals to Austro-Daimler, and Porsche promptly produced a brilliant straight-eight tourer called the Austria, a car that embodied some of the things that he had not been allowed to do in Stuttgart, such as swinging half-axle independence for the rear suspension.

The Austria was given a warm welcome when it was announced, but almost immediately afterwards Steyr's bankers failed, and the firm was taken over by Austro-Daimler, leaving Porsche little of the freedom he had come to value. Accordingly, he decided to set himself up as an independent design consultant, back in Stuttgart, and he took with him Rabe, who was to remain chief engineer of the Porsche firm from 1930 to 1966.

The Porsche Design Office

Although the new Porsche design office was to find the going hard for a few years, it did at least begin its life with a substantial contract to design a complete new car for

Wanderer. The two-liter six-cylinder car they created was a success, to be followed soon by something that was not, although it began what was to become one of the greatest success stories in the history of the motor car: it was a peoples' car, for Ziindapp, and three prototypes were built in 1932 before the decision was taken not to pursue the venture.

At this point, another project of a similar nature was proposed by NSU, and in his version for them Porsche was able to develop his theory of air cooling. The NSU had a 1.4-liter flat-four ohv engine which generated 30 bhp and-drove the car up to 70 mph but, again, the project foundered. Instead, the idea of a peoples car, a Volkswagen, was given new importance by way of instructions from Chancellor Hitler for Porsche to create something that would give the German people mobility, at no more cost than that of a medium-priced motor cycle.

Hitler and Porsche could never see eye to eye on the cost target, but were sufficiently in agreement about everything else, and this third

Volkswagen prototype embodied all the technical features on which Porsche was particularly keen. The first prototypes were built in Porsche's own garage, the next thirty by Daimler-Benz, and in 1938 the foundation stone for the Volkswagen works in Wolfsburg was laid. The stage was all set for the rest of the VW story to unfold as a separate and fascinating part of motoring history.

By this time, Porsche was famous for a quite different kind of motoring, as Wanderer had combined with three other firms to create the new Auto-Union group, which approached him to ask for a racing-car design suitable for the new 750 kg Grand Prix series. Porsche was able to tell his new customers that the design had already been done for, when the rules were announced in 1932, he had immediately discussed with Rabe how best an appropriate car might be designed, and left it to his chief engineer to draw up the detailed specification.

The Auto-Union P-Wagen

Thus began the famous Auto-Union P-Wagen, the most notorious rear-engined racing car of all time, and eventually one of the most powerful, with well over 500 bhp available from the big, lightly built and gently stressed, 16-cylinder engine which finally grew from 4.3 to 6.6 liters. Porsche was not the best chassis designer of the time, having little or no idea of the new science of ride and handling being developed in the USA or even closer to home by Englishman Maurice Olley. The Auto-Union was diabolical in its road-holding and handling, even if its point-and-squirt abilities kept it competitive against the generally more manageable Mercedes-Benz cars.

Eventually, in 1938, the Auto-Union acquired a De Dion rear axle in emulation of the 1937 Mercedes-Benz, and was transformed into a car that could be cornered with the best of its rivals. Not so very long after that, passenger-car development was halted by the war. For its duration, Porsche was naturally engaged in the development of military vehicles, as a result of which he was imprisoned afterwards in France. There, while still a prisoner, he was consulted by Renault on the design of their new 4CV car. Then, in 1947, he was released and could get back to business.

He could not do it in Stuttgart, as his old premises were occupied by the American forces, but with his son and Karl Rabe he got busy again in tiny premises at Gmund. In his absence, the firm had prepared the design for a quite extraordinary GP car to be built by

Cisitalia, featuring a highly supercharged flat-12 engine in the rear of a chassis featuring four-wheel drive and all-independent suspension, not to mention the first example of the excellent Porsche synchromesh that would become a feature on all contemporary gearboxes.

The whole car, rear suspension and all (despite the recollections of the Auto-Union), was given unstinted approval by the old man, who said he could not have done better himself - which was probably true. However he could do nothing about the financial difficulties of

Cisitalia, and when the prototype was shipped off to the Argentine where some more money was supposed to be available, he turned away to supervise the construction of a pretty little sports car based on Volkswagen mechanical components, very much in the style of the sporting VW variant that he had proposed before the War.

Ferry Porsche

It was an open two-seater, of very lightweight construction so that, despite the scant 40 bhp available from the tuned 1131cc engine, it had a lively performance. In the winter of 1948, token production started at the rate of five cars a month, with all the body panels beaten by hand over wooden formers by a gifted craftsman who had come from Austro-Daimler - yet another link, with Rabe and the aerodynamicist Mickl, from the old days when Germany was suffering the aftermath of an earlier war. Young Ferry Porsche was the man in effective charge, and he, too, had beep part of his father's organisation right from the Austro-Daimler days (he was born in 1909), and he had become extremely competent at everything from technical drawing to competition driving.

The Porsche 356

Now, he managed the development of the new little Porsche 356, and after successful trials with the open two-seater prototype, work proceeded on the streamlined coupe that had been envisaged from the start. Eventually, it was possible to resume production at Stuttgart. The first fifty coupes had been bodied by Reutter (not Beutler, as some web sites claim) but, by March 1951, the Porsche factory was able to celebrate the completion of its 500th car. In the autumn of that year, the old man fell ill, and in the following January he died. In half a century he had made his name famous wherever motoring enthusiasts spoke German; now his son Ferry was completely in charge, with the invaluable Rabe to assist him, and he went on to make it famous throughout the world.

The little 356 was a very simple car initially, with its modified VW 1100cc engine and unsynchronised gearbox, but its aerodynamics were excellent, and on 40 bhp it could exceed 80 mph, although its acceleration was modest and its VW brakes inadequate. Improvements came thick and fast: larger engines, better brakes, improved finish, refined detail, unbeatable synchromesh and, most of all, a rapidly a growing mystique that intimated a very special car for skilled drivers.

The Swedish Rally of the Midnight Sun

Competition successes helped enormously, starting with the Swedish Rally of the Midnight Sun in 1950 and making a notable impact on e the

Le Mans scene in 1951. Its roadholding left a lot to 2 be desired, the swinging half-axle rear suspension contributing to a legendary oversteer, but drivers who could control it loved it, and stayed faithful right through to the end in 1964, by which time it could be bought with a choice of engines up to 2 liters. By that time, a new model was overdue. When it arrived it was designated the 901, but Peugeot claimed all 3-digit numbers round a central 0 for themselves, so Porsche altered it to 911, by which number it has been famous ever since.

The Porsche 911

All the hallmarks of the modern Porsche tradition were evident: the clean curvaceous body, the overhung rear engine with horizontally opposed air-cooled cylinders, the utterly passive gear change, the independent suspension of unfashionably large wheels, but the details were very new. The . suspension was by McPherson struts, the geometry at the rear being determined by semi-trailing arms; the six-cylinder engine was designed for sustained high performance (though the older four-cylinder one was available for a while in the new body, in which form it was known as the 912) and once again the standard Porsche was born into a world for which its development potential was to prove more than adequate.

The semi-automatic transmission offered in 1968 was better than hard-core enthusiasts believed, but there was no argument with the fuel injection of 1970 when engine displacement rose to 2195cc. In 1972, it rose again to 2343cc, in an effort to deal with emission laws, and the high-performance 911S rendered 190 bhp to reach 143 mph. Late in 1973, appeared the first of the 2687cc engines that remained in use until 1977, more powerful and more docile (and in some instances less thirsty) than their predecessors.

Aerodynamic appendages grew beneath the noses and above the rumps of the more sporting versions in the 911 range, and for the power-hungry there came late in 1974 the Turbo Porsche, with explosive performance thanks to a 3-liter engine turbo charged to 1.5 atm. The Turbo was fast, a supercar of the highest integrity. It could accelerate from rest to 60 mph in 5.2 seconds (a match for the fastest products of

Lamborghini,

Maserati and

Ferrari).

The Porsche 924

In 1975, Porsche launched the 924, designed by VW/Audi and sold to Porsche to develop and produce. It was based freely on Audi and VW mechanical components which led many to question the nomenclature 'Porsche'. Whereas lesser companies may have faltered in their execution of a down-market product, Porsche knew exactly where its market lay and what its future held. The transaxle layout was again used in the 928 which appeared over a year later. Like all the best cars, it was designed with a clean sheet of paper and like the 924 it featured a rear-mounted, 5-speed, gearbox and adjacent clutch.

Unlike that of the 924, the 928'S engine was home-grown and a masterpiece of engineering ; an all-alloy, water-cooled V8 of 4.5-liter capacity, developing 240 bhp and 267lb ft of torque. In 1977, the 911 (now SC) series adopted the 2994cc engines of the Carrera and Turbo, suitably de-tuned. In turn, the Turbo's capacity was increased to 3299cc making it, arguably, the then fastest accelerating car in volume production. The source of all these power plants was the vigorous competition programme that, since the early days in Gmund, had been a major preoccupation of the company's research and development engineers.

The Porsche Competition Program

Encouraged by the private venture of Glockler and engineer Ramelow, Porsche began in 1953 a series of 'prototype' sports racers known as the type 550, with the engine set ahead of the rear wheels. The pushrod engine was soon supplanted by a 40HC special with roller bearings freely used, and so the stage was set for a series of works racers that grew less and less like the production cars. Nobody minded, as what appeared in any year's racer would probably end up in the road car a couple of years later; if it did not, the loss was put down to experience. In the early 1960s, Porsche entered the F2 and F1 lists with single-seaters, although they resented the minimum weight limits that cramped their style.

Supposedly because of this, they did not persevere with these cars, but of all the cars built for the 1.5 liters formula Grands Prix of 1961-1965, the flat-eight Porsche was the most elegant in design. Some of the sports racers which followed were perhaps more crude in design, but most of them worked very well and some were quite beautiful. Their story is long and complex, starting with the half-baked 904, improving with the 906 Carrera and reaching a high spot with the superb 908 which was raced in many bodily guises and with a variety of engines, the most exquisite being the flat-eight 3-liter.

Oddly the 908 was preceded by the 910, which grew difficult as it gained in speed; between them came the very low-drag 907 which won the capacity Index and came second in the thermal efficiency Index at

Le Mans in 1967 and took the first three places at Daytona in the spring of 1968. Soon afterwards, the racing department under engineer Mezger began work on the 4

½-liter flat-incline type 917, but it was going to take time to get it right, and meanwhile the minimum weight limit had been erased from the sports-racing prototype rules.

aluminum, Magnesium, Titanium and Beryllium

Porsche excelled themselves in that season with the 908: never has lightweight construction been pursued so obsessively. Anything incapable of being made in aluminum or magnesium was made in forbiddingly costly titanium, except for some brake discs which were carved out of the toxic and even more wildly expensive beryllium. The experience came in useful for the 917, which began life in 1969 with a tubular space-frame made of aluminum and weighing a mere 103 lb - hardly excessive for a car boasting 580 bhp.

Twenty-five examples of the 917 were lined up in the factory forecourt for inspection by CSI representatives in April 1969 so that the model could be homologated as a sports car in Group 5; the list price quoted a month earlier at the Geneva Show was 140,000 DM. It may have been a good investment, as the 917 was destined to have a long and extraordinary fruitful career. It won at

Le Mans in 1970 (a 4.9-liter version lapped at an outright record average of 151 mph, driven by

Vic Elford) as part of a fabulously successful Porsche season. In 1972, they won the Manufacturers' Championship; in 1972, they added an Eberspacher turbocharger to the already formidable engine and, with 850 or 950 bhp available, the 917 went on to make mincemeat of the Can-Am races on one side of the Atlantic and the Interserie races on the other.

Finally, in an attempt to put their racing efforts into perspective, the factory began a new phase with light-weight high-power variants of the production 911 in the GT categories of major events. For a few years they had hived off the management of their racing cars to private teams such as the JW /Gulf outfit, so as to save precious engineers for better things. The 210 bhp Carrera RS 911 won the 1973 Daytona 24 hour race and then made matters worse for the rest of the shocked world by winning the

Targa Florio. By the time Porsche had endowed the thing with a turbo- charger, an intercooler, 450 bhp and type 917 brakes, it was a rival for anything anywhere.

Its handling might not be as awe-inspiring as that of the standard 911, but if its freely adapted body and vast tyres did not put it quite on a par with pure racers it did last longer. By degrees, these offspring of the 911 evolved into the turbo charged 934 and 935 'silhouette' racing sports cars of the late 'seventies - virtually invincible in Group 4 and Group 5 racing and readily available in exchange for plenty of Deutschmarks. They were also visibly of the same genus as the road going Carreras and Turbos.

After legislation ended the era of the 917, the emphasis in the World Championship for Sports Cars shifted back to a 3-liter limit for normally aspirated cars and that divided by 1.4for force-fed units. 2142cc and 525 bhp proved adequate for the turbocharged 936 to uphold Porsche's honour, winning every round of the 1976 Championship. In 1977 the 936 was sent to do battle only at Le Mans, where it won. The appearance in 1977 of a turbo charged 1.4-liter 'baby' 935, to contest the 2-liter division of the German national Touring Car Championship, fired rumours that Porsche were looking for a return to Formula One.

Porsches Interpretation Of The Modern Super Car

In 1981 Porsche released the new 944 model, which was basically a further developed 924, fitted with a new Porsche designed slant-four engine with a single overhead camshaft and good for 163 bhp from its 2479cc engine. This, the enthusiasts said, was what the real 924 should always have been, and with its enhanced performance and smoothly shaped wider wheel arches it soon became a sales success. In the meantime, the 928 had arrived in 1977, as Porsches latest idea of the modern super-car.

Like the 924, it had a front-mounted, water-cooled, engine, and rear gearbox, and broadly similar styling outlines, but it was all-new, and totally Porsche. Designed to attack the lucrative expensive coupe market sector, it was smooth, silent, extremely efficient, but somehow without much character as first revealed. The rounded styling, with its large expanse of glass and wide hips was perhaps neither pretty nor aggressive, something many believed a sports car should be. Its engine was a new light-alloy V8 unit of 4474cc, with single overhead camshafts per bank, and the inevitable Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection, good for 240bhp at 5250rpm. There was a choice of either five-speed manual or three-speed automatic transmissions, both courtesy of the good folk at Mercedes-Benz.

The original 928 was actually slower than the 911, and because it was heavier it also suffered the inevitable fuel consumption woes. Sales were slow at first, and so from 1979 it was joined by the 928S, where the engine size was enlarged to 4664cc and resulting power increased to 300bhp. New aerodynamic aids were added, most notably a wrap-around rear spoiler under the tailgate glass. Importantly for the time, the revisions to the car meant it could join the "Over 150mph" class, and was capable of 0-60mph in 6.5 seconds. The 928 S2 which followed had 310bhp on tap, and naturally even greater performance. The latest development, for the start of the 1984 model year was the enlargement of the 'base' engine size, once again enlarged, this time to 3164cc and good for 231bhp at 5900rpm - and just to confuse everybody the "Carrera" name was resurrected for a third time.

Footnote: Although Ferdinand Porsche is believed to have been politically naïve, consumed with engineering, he was arrested after the war and charged with collaboration. He was freed in 1947 after almost twenty months in prison. His health was poor. In the meantime, the Porsche firm did whatever it could to stay in business. It designed its own sports car, the first car to carry the name Porsche.

Type 356 was the project number. One year after Ferdinand Porsche was released from prison, he witnessed the birth of the Porsche sports car. The very first Porsche, a hand-built aluminum prototype, was completed on June 8, 1948. Ferdinand Porsche died on January 30, 1952, from the effects of a stroke he had suffered earlier. He died after seeing his dream of a Porsche sports car become a reality.

Recommended Reading:

The House Of Porsche

The House of Porsche - A Pictorial History

Ferdinand Porsche

Porsche Car Reviews

The History of Porsche (AUS Edition)