|

Peugeot

|

1890 - Present |

Country: |

|

|

Jean-Pierre Peugeot

At the time of the French Revolution, Jean-Pierre Peugeot was mayor of Herimon court, in the district of Montbeliard, which was then under the domination of the Princes of Wurttemburg; he was a weaver and dyer by trade, and had four sons, of whom the two eldest, Jean-Frederic and Jean-Pierre, decided to set up a small steelworks in the neighbourhood of Sous-Cretet, the village in which they had been born.

Before long their output was composed almost entirely of saws, and Jean-Frederic, who was not yet twenty, had the bright idea of using their rolling mills to mass-produce saws, which resulted in a cheaper, better-quality article. By 1825, eleven years after the death of Jean-Pierre senior, the founding father of this remarkable dynasty, the fame of the Sous-Cretet saw-works had spread throughout France.

The two brothers had seven sons between them; soon this hardworking family team decided to expand, and they set up a new factory at Terre-Blanche. Then, in 1843, they took over a thriving ironmongery manufacturing business founded in 1820 by the Japy family, of Beaucourt. Within three years, however, the Peugeot family had been split by arguments, and the various factories distributed between them.

Peugeot Freres

Jean-Frederic and his sons continued to make saws and tools at Sous-Cretet d'Herimoncourt, and opened a new branch factory at Pont-de-Roide, while the sons of Jean-Pierre II, Jules and Emile, took over the Terre-Blanche and Valentigny works, under the name of 'Peugeot Freres'. The Peugeot Freres concern was the more go-ahead of the two family businesses, and in 1855 Jules and Emile found an entirely new market for the company's skill, in manufacturing thin steel rods.

The Empress Eugenie had brought the crinoline back into fashion as, she claimed, reasons of aesthetics; but the new look crinoline was given its shape by whalebone rods, not the padding and petticoats of the era of Louis-Phillipe. Women were anxious to copy the Empress's lead - but whalebone stays were extremely expensive, and were not always obtainable in the correct length to satisfy the demands of fashion. Which is where Peugeot came in.

Les Fils de Peugeot Freres

The brothers bought an old mill at Beaulieu, equipped it with the necessary machinery and, in 1857, started mass-production of steel crinoline stays and hoops. Moreover, they were clued-up enough to keep pace with the changing contours of feminine underwear through the succeeding decades. They made stays for the demi-crinoline, then for the demi-terme, the tournure and the coussinet, finally branching out into corsetry. Jules and Emile both died in 1865, and the company became 'Les Fils de Peugeot Freres'; there were already more than 500 workmen in their three factories, producing all kinds of metalwork, from peppermills to umbrella ribs.

Armand Peugeot

In the 1880s the techniques of producing thin metal rods, that had proved so useful in making crinolines, were adapted to the manufacture of spokes for the wheels of high-wheeler bicycles. Soon Peugeot was one of France's leading cycle makers, having plunged into the market with that 'boldness tempered by great wisdom' that characterised all their ventures. At that time, the leading light of the company was Armand Peugeot, son of Emile, who had spent a great deal of time in England studying production techniques in the factories of Leeds (as, some years earlier, had Gottlieb Daimler).

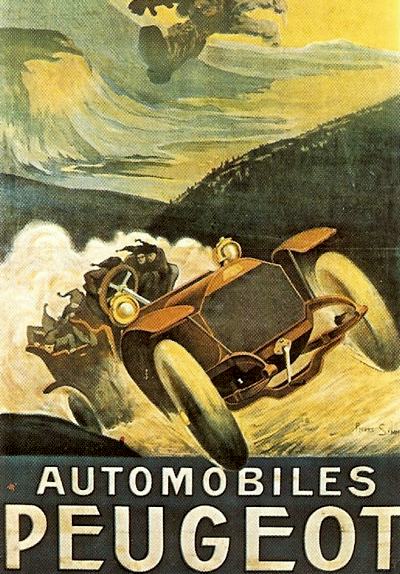

Automobiles Peugeot.

Automobiles Peugeot.

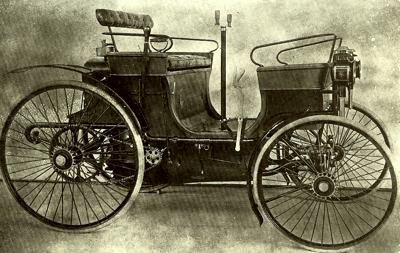

1891 Peugeot tipo 3 - powered by a twin-cylinder 2hp Daimler engine.

1891 Peugeot tipo 3 - powered by a twin-cylinder 2hp Daimler engine.

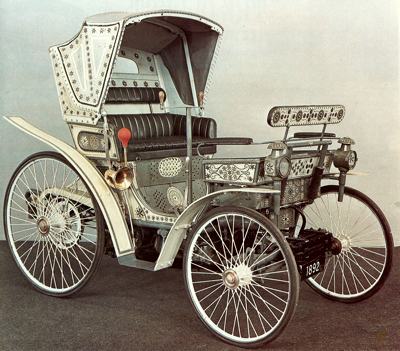

The vis-a-vis Peugeot of 1892. It was powered by a Vee-Twin 1018cc

The vis-a-vis Peugeot of 1892. It was powered by a Vee-Twin 1018cc

engine which gave a top speed of 30 kph.

1892 Peugeot Victoria, powered by a twin-cylinder Daimler engine.

1892 Peugeot Victoria, powered by a twin-cylinder Daimler engine.

1893 Peugeot Vis-a-Vis.

1894 Peugeot 12hp Tourer.

1894 Peugeot 12hp Tourer.

1904 Peugeot Tonneau, a four seater runabout.

1904 Peugeot Tonneau, a four seater runabout.

1905 Peugeot Bebe, arguably the first ever "frog-eye".

1912 Peugeot Bebe.

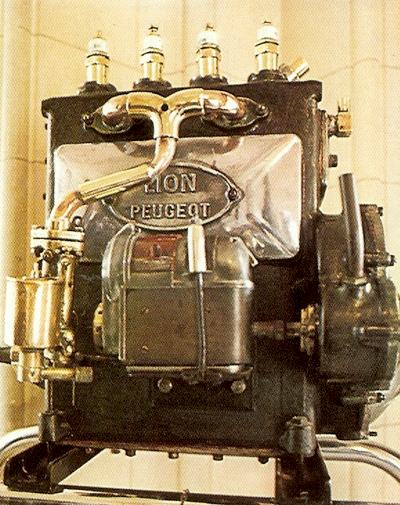

The famous 10hp Lion-Peugeot engine built by Bugatti.

1907 Peugeot Tipo 91.

1907 Peugeot Tipo 91.

1909 Peugeot Phaeton.

1909 Peugeot Phaeton.

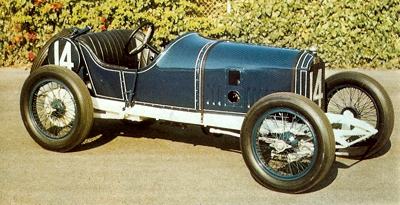

1913 Peugeot L3 Racer.

1913 Peugeot L3 Racer.

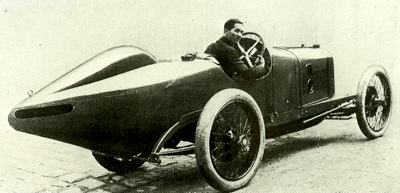

Boillot pictured at the ACF Grand Prix in 1914. The racer was powered by a 4.5 liter engine.

Boillot pictured at the ACF Grand Prix in 1914. The racer was powered by a 4.5 liter engine.

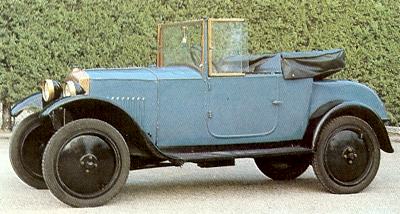

1921 Peugeot Tipo 163, powered by a 1437cc engine.

1921 Peugeot Tipo 163, powered by a 1437cc engine.

1924 Peugeot 172 BC.

1924 Peugeot 172 BC.

1925 Peugeot 172, which was powered by either a 667cc or 720cc engine.

1925 Peugeot 172, which was powered by either a 667cc or 720cc engine.

1929 Peugeot 201.

1929 Peugeot 201.

1932 Peugeot 201 update.

1932 Peugeot 201 update.

1938 Peugeot 402B Streamliner. Its engine developed 63 bhp, and the car could reach 125 kph.

1938 Peugeot 402B Streamliner. Its engine developed 63 bhp, and the car could reach 125 kph.

A Peugeot 404 competing in the 1968 East African Rally. Incredibly well built, it was their reliability that would make them so successful at rally events around the world for so many years.

A Peugeot 404 competing in the 1968 East African Rally. Incredibly well built, it was their reliability that would make them so successful at rally events around the world for so many years.

Peugeot 204 Station Wagon.

Peugeot 204 Station Wagon.

1975 Peugeot 504 Wagon.

1975 Peugeot 504 Wagon.

Peugeot 504 Cabriolet with coachwork by Pininfarina. This was one of the first Peugeots to use the Peugeot-Volvo-Renault V6 twin cam engine.

Peugeot 504 Cabriolet with coachwork by Pininfarina. This was one of the first Peugeots to use the Peugeot-Volvo-Renault V6 twin cam engine.

1975 Peugeot 304 Cabriolet, powered by a 1288cc engine.

1975 Peugeot 304 Cabriolet, powered by a 1288cc engine.

In 1974 the flagship of the Peugeot range was the 604. Although designed by Pininfarina, many thought it too conservative.

In 1974 the flagship of the Peugeot range was the 604. Although designed by Pininfarina, many thought it too conservative.

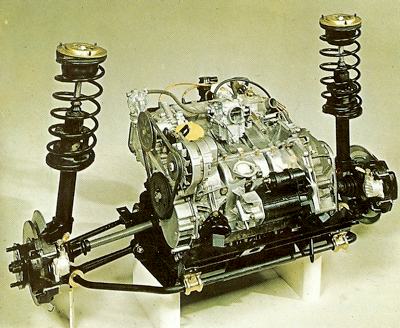

The engine and front suspension of the Peugeot 104.

The engine and front suspension of the Peugeot 104.

Peugeot created the "Hot Hatch" genre when it released the 205 GTi.

Peugeot created the "Hot Hatch" genre when it released the 205 GTi. |

The 1889 Paris Universal Exposition

Around 1889, Armand foresaw the potential of the motor car, and built a horseless carriage; not wishing to waste time in fruitless experiment, he decided to use proven components and built a three-wheeled steam car in conjunction with Leon Serpollet. The steam car proved prone to break-down, as was amply proved by an incident-filled trip from Paris to Lyon, and Armand Peugeot began to look around for some other motive power. He displayed the steamer among his other products at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, where it attracted the attention of Emile Levassor, who had just acquired French rights to the Daimler engine patents; together with Gottlieb Daimler, who was visiting the Exposition, Levassor hurried to see Armand Peugeot at Valentigny to convince him of the superiority of the internal-combustion engine.

At that time Panhard and Levassor had no interest in building cars: they were quite happy to manufacture engines for sale to industry and would-be motor-vehicle constructors. Peugeot decided to use the Panhard-Daimler motor in his next carriage; but he remained unsure as to where best to locate the engine, at the front or the back. Levassor argued that the logical place for the power unit was at the back of the vehicle, as that would spare the occupants the unpleasant smells emanating from the engine. Peugeot countered that it seemed sensible to place the motor at the front of the car in the interests of better weight distribution.

Both men must have been powerful advocates, as each convinced the other of the validity of his own particular point of view. When Peugeot went into production, he built his cars with the engine at the back; and when Panhard and Levassor became automobile manufacturers, all their vehicles, save for a handful of prototypes, were front-engined. The first Peugeot petrol cars, which appeared some time in 1890, reflected their manufacturer's long experience of cycle manufacture, with tubular chassis (through which the cooling water was circulated) and spidery wire wheels. The car was, in many respects, more advanced in conception than the majority of its contemporaries. For example, a transverse front spring and long rear quarter-elliptics gave the car three-point suspension; quadrants bolted to the front of the frame kept the forward axle in alignment.

The Four-Speed Sliding-Gear Transmission

After experiments with friction drive, the company adopted a four-speed sliding-gear transmission, whose design almost certainly predated the brusque et brutale transmission of the Panhard, and a cone clutch, while the steering was pure cycle, with handlebars controlling the front axle via a chain-and-sprocket mechanism which actuated twin tie rods. 'In some respects,' noted Worby Beaumont, 'the carriage was of superior arrangements for appearance, but the position of the motor at the rear, where most of the passenger weight came, put an unnecessary load on the hind wheels, and for good steering too little on the front wheels. The Peugeot position for the motor is moreover inferior with respect to convenience of the driver.'

Doriot and Rigoulot

But the Peugeot company had no qualms about the performance potential of their new product, and in September 1891 sent one of the earliest examples on a remarkable endurance run. Driven by the engineers Doriot and Rigoulot, the Peugeot 2CV Quadricycle a gazoline followed the competitors in the Paris-Brest-Paris cycle race, covering the 2047 km round trip from Valentigny to Brest and back in 139 hours 'without a moment's trouble'. That same year, the company sold five cars to private owners, a figure which rose to 29 in 1892. Demand grew steadily, if not spectacularly; Peugeot were now competing with their engine suppliers, Panhard & Levassor, who had at last decided to build complete cars.

Both marques were technically eclipsed by the De Dion Steamer in the 1894 Paris-Rouen Trial; but the event's cumbersome regulations were then brought into play to rule that the De Dion, although it had finished first, was too fast and too heavy, and that the two marques petrolistes were joint winners. On road performance, the Peugeot cars were markedly superior, having finished second, third and fifth. It was apparent that Peugeot were experimenting with styling, as Lemaitre's second-place car had been a four-seated phaeton fitted with clumsy-looking wooden wheels. The car which came third (carrying Pierre Giffard, who had conceived the trial) was the usual wire-wheeled version, and Koechlin's fifth-place car had been a wagonette with the power unit apparently mounted under the driver's seat.

Michelin Pneumatic Tyres

It was around this time that Peugeot started receiving export orders: in 1894 the Bey of Tunis ordered a vis-a-vis, which was richly decorated with stylised floral designs, while in 1895 the Francophile Sir David Salomons imported a Peugeot into England. In 1895 there was a rise in sales to 75 cars, and the adoption of a vertical-twin engine, still rear-mounted, still with hot-tube ignition (although the outward form of the cars was unchanged); a team of three, driven by contremaitres choisis and equipped with picnic baskets to keep the crew fed on the long journey, was entered for the Paris-Bourdeaux race. Although Peugeot were judged the official winners of the nice, theirs was a hollow crown, as they had only won on a technicality, and Emile Levassor's first-to-arrive Panhard had won the moral victory. The race was also noteworthy for the first appearance of Michelin pneumatic tyres, on the Peugeot L' Eclair, so-called from its zig-zag, puncture-prone motion.

Peugeot at last began to make their own engines in 1896: designed by Rigoulot, the new power unit was an 8hp horizontal-twin, set at the back of the chassis with the cylinder heads pointing rearwards. Hardly the coolest place to mount the engine, a fact apparently recognised by the provision of a gilled-tube radiator between the front wheels. Hot-tube ignition was still standard, but the design of the engine was chiefly notable for the peculiar exhaust-valve actuation, in which a bell-crank lever followed a continuous crossover 'tramline' formed in the flywheel (which was between the crank throws). Moving first to the left, then to the right, the bell-crank rocked striking arms which held each exhaust valve open for half a revolution. The engine also had a float-fed spray carburetor and hemispherical combustion chambers in a detachable cylinder head (although it is certain that no-one realised the technical significance of this feature at the time it was produced).

Societe Anonyme des Automobiles Peugeot

A front-engined wagonette won the class for six-seated cars in the 1896 Paris-Marseilles-Paris, but the racing scene was already dominated by Panhard & Levassor; against whose steadily developing front-engined cars the five-year-old basic design of the Peugeot looked somewhat antique. Not that the marque was without its imitators, as the contemporary Rochet-Schneider was virtually a carbon copy of the Peugeot models of the period. The fact that car manufacture was now at least as important to Les Fils de Peugeot Freres as corsetry and cycles was shown by the formation, in 1897, of a separate car manufacturing company, Societe Anonyme des Automobiles Peugeot, with a factory at Audincourt.

Sales were still riding, reaching 300 in 1899, at which time the automobile population of France was estimated at little more than 1200 vehicles. That year saw a special racing Peugeot with an engine rated at 20hp, with a swept volume of 5850cc; driving a car of this type, Lemaitre won the 75-mile Nice-Castellane-Nice race in March 1899. However, the days of the rear-engined Peugeot were numbered, at least as far as racing was concerned. In the 1900 Paris-Toulouse-Paris event, the marque was represented by a new front-engined 30hp model, with the 5850cc twin-cylinder engine mounted under a crudely-designed bonnet fronted by a massive gilled-tube radiator; however the car was still no match for the

Mors or Panhard racers.

The Peugeot Bebe

Forward-mounted engines reached production status at the end of 1901, when a new range of cars was revealed at the Paris Salon. There was an 8hp twin and a 15hp four, but incontestably the most popular was the diminutive 652cc single-cylinder Bebe, a neat little car with a De Dion type bonnet and shaft drive to a live rear axle. During its two-year production life the Bebe was imported in relatively large numbers to Britain, where the agent was the ebullient Charles Friswell. Hitherto, Peugeot design had always been a little conservative: now the marque became a style-setter. The larger models were now built on the very best Mercedes lines, with pressed-steel frames, mechanically operated inlet valves and distinctively square-cut radiators. Live axles became universal in 1904.

The 1903 range consisted of four cars: the 5hp Bebe, a new 6

½hp which could carry a four-seated tonneau body, and the 8hp and 12hp Mercedes-type models-according to the catalogue, the 8hp offered 'automatic lubrication by water pressure', a curious feature that was soon supplanted by conventional pump-and-splash oiling. Peugeots of the new pattern had already appeared in competition, Roquette taking nineteenth place in the 1902 Paris-Vienna with a monstrous 11,322cc sohp Peugeot, although his two team-mates fell by the wayside, as did Callois's 16hp, 2126cc twin-cylinder in the Voiture Legere classification. That, however, was the last seen of Peugeot on the competition scene for a decade, at least as far as the mainstream factory was concerned.

Lion-Peugeot

In 1906 Robert Peugeot established his own car-manufacturing company in the Valentigney works under the name Lion-Peugeot, the Lion being the Peugeot emblem. Designed by Michaux, the Lion-Peugeot range was intended to fill the place at the bottom end of the market left by the demise of the Bebe Peugeot; but the two marques were directly competitive. It is as a competition car that the Lion-Peugeot is best remembered, as the crazy design of the company's voiturette racers of the 1905-1911 era epitomised a breed of cars built to circumvent regulations that restricted the bore, but took no note of the stroke, resulting in single, vee-twin and V4 engines with such enormously long strokes that forward vision over the bonnet was almost impossible. Most outlandish of all was the 1910 VXS, whose 2815cc engine had dimensions of 80 x 280mm, and was good for 95mph in overdrive top.

The two Peugeot factories were reunited in 1911, but the Lions continued to race until the following year, the touring Lion-Peugeots surviving until 1913. Meanwhile, the products of Automobiles Peugeot had continued to develop along conventional lines. Proof of their quality was given in the 1905 Coupe Rochet-Schneider, a tough touring car trial organized by the Automobile Club de Suisse over a 102km circuit based on Zurich. The award was given to the car which proved the best all round with regard to reliability, fuel consumption, speed on hills and average speed: the winner was the 15hp Peugeot of M Perret, of the Automobile Club d'Auvergne.

The 1907 Paris Salon saw the announcement of the first 'Peugeot six-cylinder model, while at the same show, the name of A. Peugeot was linked with that of Tony Huber, who had recently turned from making complete cars to power units. By 1910, the Peugeot range had grown to include seven models; a 1149cc two-cylinder, and four-cylinder models of 2001cc, 2619cc, 3817cc, 3989cc, 5027cc and 6082cc. And it was during 1907 that another car production plant was opened at Sochaux, which was to become the centre of manufacture in 1925.

Ettore Bugatti's New Bebe

A new Bebe was born (or rather, adopted) in 1912: originally designed by Ettore Bugatti this diminutive 850cc four-cylinder design was sold to Peugeot. Its side valve engine was cast en bloc, and drove the rear axle through a two-speed transmission in which twin concentric propeller shafts with toothed ends were meshed with two rows of teeth on the crown wheel. A real big car in miniature, this delightful voiturette was relatively affordable - however the really big event of 1912 was the marque's re-entry into racing, with one of the classic designs of all time. The genesis of the new models was the direct result of the reconciliation between Peugeot and Lion-Peugeot, and with the Lion-Peugeot racing team came a unique trio of driver-engineers - Georges Boillot, Jules Goux and Paolo Zuccarelli.

Now that they - and Robert Peugeot - had the resources of the two Peugeot car companies behind them, they felt that it was time to branch out from voiturette racing, and really move into the big time: but to do that, they needed a car suitable for the grandes epreuues. Goux, who knew Robert Peugeot well, was given the task of ensuring the trio were well qualified to develop such a car: the Peugeot drawing office attempted to pour scorn on the proposal, and christened Boillot, Zuccarelli and Goux Les Charlatans, but Robert Peugeot, who was now president of the reunited company, gave the project his blessing.

Ernest Henry

A Swiss engineer, Ernest Henry, who at 26 was the same age as the three drivers, was charged with transmuting their ideas into reality: the Three Musketeers had found their d'Artagnan. The engine the foursome created was an epoch-making design: for the first time, twin overhead camshafts actuated four inclined valves per cylinder. It seems as though the broad overall concept was that of Zuccarelli, as the portly Italian had worked with

Hispano-Suiza, where there had been some preliminary design work carried out on a single-ohc racing engine, even though it is highly unlikely that this power unit was completed before Zuccarelli left to join Peugeot.

Boillot and Goux, on the other hand, had only been working on the esoteric Michaux-designed Lion-Peugeot engines, though both were more than competent engineers: Jules Goux was a graduate engineer of the Arts et Metiers in Paris, and Boillot seems to have been as skilled an organiser as he was as an engineer and driver. Working in the experimental shop which Robert Peugeot had allotted them in a corner of the Lion-Peugeot works, Boillot, Zuccarelli, Goux and Henry completed a prototype racer intended for the French Grand Prix, which was being revived in 1912 after a four years' absense. But, no doubt prompted by malicious whisperings from the 'official' design office, it seems that Robert Peugeot had doubts about the potential of the 7.6-liter car, and proposed a trial between the Peugeot and a Bugatti - almost certainly the new 5026cc 'Type Garros' with a single overhead camshaft and three valves per cylinder.

Peugeot vs. Bugatti

The Peugeot achieved 115mph in the run-off, the Bugatti could not better 99.4mph - and the Peugeot engineers were commissioned to produce a team for the Grand Prix. Oddly enough, the cylinder dimensions of their car (110 x 200mm) were exactly those specified for the shambolic 'Grand Prix' organised in 1911 by the Automobile Club de la Sarthe, usually known as 'Le Grand Prix des Vieux Tacots' (Old crocks' GP) after the old age and ability of the entries. And a team of Lion-Peugeots'had been promised for that event - but never materialised: In fact, the 1912 Grand Prix was organised as a formula libre event, which left the new Peugeots opposed against behemoths like the 14,137cc ohc Fiats, or the even more monstrous 17-liter Lorraine-Dietrichs and, as this race was to be a two-day affair run over 956 miles, it was possible that the lower stresses produced in the larger, slower-turning engines might prove synonymous with reliability.

And so, at first, it seemed ... Goux was disqualified after a flying stone had holed his petrol tank, compelling him to take on a fresh supply away from the pits, in contravention of the regulations, while Zuccarelli's radiator hose broke twice, causing his engine to overheat disastrously on an isolated leg of the 49-mile circuit. At the start of the second day, Boillot was lying second, between the Fiats of David Bruce Brown and Louis Wagner and, when Bruce Brown was disqualified for a similar offence to the one which had eliminated Goux, it seemed as though the Peugeot, which was touching 120mph on the straights, was all set to win the race. Then, on the eighth lap, Boillot's gearbox jammed ... he managed to free the selectors with a tire lever, but could only use second and top while, for good measure, he reversed the rear universal-joint housing, which had been cracked by a stone, allowing all the grease to escape.

During this 20-minute pit stop, Wagner caught up, but the Fiats had been irretrievably delayed by tire troubles, and Boillot, running mostly on top gear, which reduced his speed on hills by up to 32mph, managed to maintain his lead to the finishing line, winning at the creditable average speed of 68·45mph. Behind him came Wagner's Fiat and three British 3-liter Sunbeams running in the Coupe de I' Auto, which was run concurrently with the Grand Prix to keep the entry figures up. For Boillot, though, France would have suffered a defeat as humiliating as the German walkover in the 1908 Grand Prix: 'Sans Peugeot,' concluded Charles Faroux of L' Auto, 'Quelle terrible defaite pour nous'.

Coupe de Sarthe

Three months later, Goux won the 'Coupe de Sarthe' at an average. of 72.2mph, then, the following spring, eclipsed the US opposition at Indianapolis with a 75·92mph win in the 500 mile race, lapping the Brickyard at times at 93.5 mph. Improved racing cars were built for the 1913 French Grand Prix, with the capacity reduced to 5655cc to allow for the fuel consumption formula which was to be used in the event. But while testing one of the new cars on a long, deserted road in Normandy, Zuccarelli had been killed when a local farmer drove a haycart out of a concealed side-turning; his place in the team was taken by a new driver, Delpierre.

The new cars were as fast as their larger forebears: they pioneered the use of ball-bearing crankshafts and dry-sump lubrication, a layout which was soon to be widely copied, as was the use of a train of gears to drive the camshafts (which were themselves carried on ball-bearings). Perhaps more remarkable was the performance of a 3-liter version built to the Coupe de I' Auto formula, as this car had a top speed of 95mph, and, in Boillot's hands, carried off the race for which it had been designed. Then the larger car, driven by Georges, won the Grand Prix with consummate ease, making Boillot the first-ever two-times winner of this event; Goux was second.

During 1914 the Peugeot design was blatantly copied by Straker-Squire, Humber and Sunbeam in the Isle of Man TT races, and subsequent copyists ranged from W.O. Bentley to Harry Armenius Miller, but in America Peugeot were part of the European contingent which trounced the home team at Indianapolis. Although ex-Peugeot racer Rene Thomas won the '500' in a 623Scc Delage, second man home was Duray in a 3-liter Peugeot. Boillot's 1913 GP car was the fastest in the race, setting a new lap record of 99.5 mph before a burst rear tire caused a chassis fracture and compelled his retirement.

Peugeot vs. Mercedes

There were new races for the 1914 French Grand Prix, run to a 4.5-liter capacity limit, but in the race it soon became clear that they were outclassed by the Mercedes, with their engines derived from aircraft practice. The only chance lay in the fact that the Peugeots now had four-wheel braking, against the rear-wheels-only retardation of the Mercedes. Boillot played this for all it was worth, managing to hold the lead from the sixth lap. But the new long-tailed body of his car upset the weight distribution, contributing to tire troubles, and the inevitable mechanical strain of attempting to force the pace with a car that was slower than its rivals ended Boillot's race on the 20th lap when the Peugeot, already reputedly suffering from a broken valve, expired from compound mechanical problems, and Georges retired to a nearby cafe to watch the Germans sweep home to a convincing victory.

Although Georges Boillot was shot down over the Western Front in 1916, his younger brother Andre appeared at the wheel of racing Peugeots after the war. The cars had upheld their honour during the hostilities in the main American races, which included second place at Indianapolis in 1915 and victory there in 1916, as well as first places in the 1915 Grand Prize and

Vanderbilt Cup events. Wilcox's 1914 GP Peugeot won the 1919 Indianapolis 500, too, and thanks to Harry Miller, many of the subsequent Indy victors were Peugeot-inspired. A 1914 Peugeot was even entered in the 1949 500, lapping at 103 mph in practice, but failing to qualify for the race.

Andre Boillot

Andre Boillot won the 1919

Targa Florio with a 2·5-liter Peugeot built for the abortive 1914 Coupe de l'Auto, and which had covered over 200,000 km as his brother's staff car (taken over by Charles Faroux) before it came to start in a race. The younger Boillot drove a melodramatic Targa, making 6 spectacular excursions from the circuit, before finishing twice, once in reverse and once the proper way round; this was after ramming the grandstand avoiding spectators on the track. He then collapsed over the steering wheel crying: 'C'est pour la France!' It was immediately said that Andre Boillot was as skilful and daring and even more reckless than Georges had been, but this was his greatest race.

Boillot finished third in the 1925 Targa, and first in the 1922 and 1925 Coppa Florios, won the 1923 and 1925 Touring Car Grands Prix and the

24 Heures du Spa in 1926, driving sleeve-valve Peugeots in all these events. However, he was killed in 1932 testing a prototype sports car. In any case, Peugeot had dropped out of Grand Prix racing in 1921, following a number of depressing failures on both sides of the Atlantic with a curious triple-ohc, five-valves-per-cylinder racer designed by Marcel Gremillon, one of the official Peugeot drawing office team who had criticised the designs of Les Charlatans in pre-war days. Henry and Goux had, by now, transferred to the Ballot organisation.

La Quadrilette

On the touring-car front, the 1919 Paris Salon saw a line-up of 10hp and 14hp four-cylinder models, the larger of which was an updated version of the pre-war Type 153, and a 25hp 6-liter sleeve-valve six. Plus, most significantly, 'Un nouveau modele sensationel', La Quadrilette, which, claimed its makers, solved the question of the popular economic car. La Quadrilette was really a refined variation on the cyclecar theme, paying the same annual 100 francs tax as a crudity like the Bedelia, but had a proper four-cylinder engine of 'faible cylindree' (628cc); this concept was, however, just about all it had in common with the old Bebe, Peugeot waxed eloquent about the new model: 'In the face of the inflated price of petrol, oil and tyres, which forces many people to do without the car which is necessary for their occupations, the Societe Peugeot, anxious to meet public needs, has designed a model which carries the minimum maintenance costs.

'La Quadrilette Peugeot has an infinitesimal thirst (less than five liters of petrol per 100 kilometres) and consumes an equally insignificant quantity of oil. Furthermore, it uses hardly any tyres. 'Thanks to its very small width (1 meter 16 cm - a motor cycle and sidecar is 1 metre 45 cm), La Quadrilette can travel on the narrowest country roads; in built-up areas and on the busiest roads it can wriggle through the traffic, thus making appreciable time economies for its driver. 'It can go anywhere with ease. 'Finally, La Quadrilette is not a hastily constructed cyclecar. It is the first cydecar built as throughly and as seriously as a full-size car. 'As the result of these qualities, La Quadrilette Peugeot is the perfect vehicle for the rapid and economic transport of two people. La Quadrilette is the ideal model for Doctors, Veterinary Surgeons, Mobile Policemen, Businessmen, Commercial Travel- lers, Representatives, etc. A journey in the Quadrilette costs less than the third-class railway fare.'

The Contest of the 5-liter Petrol Can

The chassis of the new model was a pressed-steel 'punt' suspended on a transverse front spring and quarter elliptic rears. Because of the car's narrow width, seating was minimal: either two seats in tandem or two staggered seats for exceptionally close (and thin) friends or relations. Its economies of performance were amply proved by awards in such euphoniously named events as the Contest of the 5-liter Petrol Can (Concours du Bidon de 5 liters), held at La Ferte-Bernard in 1920, in which La Quadrilette won its class with a consumption of 117km 900 metres on 5 liters, or the One liter Petrol Can Contest at Geneva, covering 27km 405 metres on 1 liter of fuel. The cylinders of the first Quadrilettes were obviously too small, as the swept volume was soon increased to 667cc; in 1925, capacity was again raised, to 719cc, while the last Quadrilettes of 1929 had 694cc engines, a curious step in view of the fact that the poor little power unit now had to drag five-seater coachwork around with the aid of a 7.25:1 top gear.

Apart from the Quadrilette, the 1923 range consisted of the 1437cc 10hp, available with torpedo, de luxe torpedo or boat-tailed sporting four-seater bodywork, the 2950cc 15hp (normal or long chassis, colonial and sporting models were offered), the 3828cc sleeve-valve 18hp (long chassis or Grand Sport) and the 25hp sleeve-valve six de haut luxe. Peugeot continued to expand during the 1920s: factories were acquired from the moribund Bellanger and De Dion Bouton companies in 1927, and new models began to appear from 1928 on, starting with the 1991cc Type 183, which was mechanically revised at the end of 1930, appearing at Olympia that year in three-seater cabriolet-coupe form.

The Peugeot Type 201X

Another new model had appeared at the 1929 Paris Salon: the Type 201, probably the least expensive four-passenger car on the French market, with a 1122cc engine, and reversed quarter-elliptic rear springs, a feature normally associated with Bugatti. Nor was this entirely accidental, as Bugatti was back in the Peugeot orbit. In 1930 he produced his Type 48, a 995cc supercharged ohc engine, which was in effect half a Type 35 power unit. This was supplied to Peugeot for the Type 201X, a new sporting model, with which Andre Boillot took the 1500cc class 24 hours record in 1931. However, he was killed testing a Type 201X in 1932, and the model was dropped after only a few examples had been completed.

At the end of 1931, the 'Lion-Peugeot' moniker was revived for a new version of the Type 201 with independent front suspension by a transverse spring and long locating links which replaced the conventional axle beam. The conventionally sprung 201 was still available. The 1933 Paris Salon saw the 201 and 301 models on display: a novel feature of the 301 (which was basically a six-cylinder version of the 201) was a vertically sliding windscreen, operated by a small handwheel. 'The screen moves upwards into the roof, where there does not seem to be room for it, and one gets the impression that the glass must bend over,' said The Motor.

The First Peugeot Convertible

There were coachwork novelties at the 1934 Salon, too: 'One of the real high spots in body design is to be seen on the Peugeot stand; an exhibit which collects an enormous crowd,' wrote The Motor's Paris Correspondent. 'This is a self-transforming body on one of the new six-cylinder chassis, in which the change from open to closed, or vice versa, is made mechanically without any effort on the part of the driver beyond that of pushing a button. The device is shown in operation, and the impression given is almost uncanny, for at one moment you are looking at an open sports two-seater, and the next, at a very smart, fixed-head coupe.

A few seconds later the body returns to its original open form. 'The complete "top" (roof and sides) is housed in the streamlined tail, and when a button on the instrument board is pressed, two hinged rams, operated by compressed air, open the lid ofthe boot, while two more rams lift the top out of its compartment and place it gently over the heads of the passengers. The compressed air is supplied by a small electrically driven air pump, current for the motor being taken from the ordinary accumulators of the car. The rams operate like those of a tipping lorry, but they are naturally of lighter construction. When the top is placed in position, one has a genuine closed body guaranteed to be both waterproof and rattleproof. After the transformation to open has taken place, the lid of the boot is closed automatically by its own rams.'

The Peugeot Type 402 Streamliner

Another eyecatching feature of the Peugeot exhibit was that all cars on the stand were painted the same shade of light blue. Although these models were as handsome in appearance as any of their contemporaries, by the following autumn it was apparent that someone at Sochaux had had a bad attack of the 'airflows', as the new 2.1-liter Type 402 was streamlined to an exaggerated degree. The body was so wide that it had to be supported on a subsidiary frame outrigged from the chassis side-members-there was seating forthree in front - while the headlamps and accumulators were mounted between the sloping radiator grille and the radiator of the car.

Cotal Electric Epicyclic Transmission

Overhead valves and worm final drive were features of the mechanical specification, as was the option of a Cotal electrically operated epicyclic gear-box - practically automatic in action - which had been adopted, incorporating the Fleischel 'declencheur' control, which was controlled by engine suction and centrifugal force. As the engine speed and load varied, so the 'declencheur' operated a switch mechanism which brought the Cotal gears automatically into operation. The device did not, however, remain long in production, and by the following autumn only the standard Cotal box was available.

Around this period, the coach builder Emile Darl'Mat was offering a sports model confected round a hotted-up 402 engine in the 302 chassis; around 200 Peugeot-Darl'Mats were built between 1936 and 1939, and this sub-marque took 7th, 8th and 10th places in the

1937 Le Mans 24 Hours, and 5th in

1938 Le Mans. Alongside the super-streamlined 302 and 402 models, with their full-width bodywork and 'parrot-cage' radiator grilles, the 201M, announced at the 1936 Salon, looked retrogressive, as it had externally mounted headlamps and running boards, and carried four-door, six-light saloon coachwork of orthodox appearance, but it paled into insignificance alongside 'the car of 1940', which was the centrepiece of the Peugeot stand.

Designed by M. Andrean, who had carried out a great deal of research into aerodynamics, the car was basically a 402: 'The machine is a wonderful piece of work, whether one cares for that kind of thing or not. The body accommodates four people comfortably and is not difficult to enter, whilst in the aeroplane tail, complete with a fin, spare wheels are lodged. The feat looks impossible, but when hinged side panels are opened, the wheels are definitely disclosed within the panel. 'The "stabilising fin" ends in a vertical bumper like a rubber-edge scimitar, on top of which is perched a red light, and illuminated number plates are mounted on each side of the sloping tail panels; an arrangement which might not satisfy the police in England but is readily accepted in France.'

The 1938 Paris Salon

The 1938 war scare caused the Paris Salon to be postponed for a week owing to the fact that many of the men connected with the organisation of the show had been temporarily mobilised and, when the doors of the Grand Palais eventually opened, the new Peugeot range was one of the leading attractions. Already the pernicious effects of an excessive fuel tax were making themselves apparent in the shape of a new generation of over-bodied, under-engined French cars, and the largest of the 1939 Peugeots, an updated version of the 402, looked far too heavy for its 2140cc power unit. This was a four-cylinder engine, the 601 six-cylinder unit having been dropped after less than three years in production. Both the 2.1-liter and the new 1133cc power units had wet-liner construction, and all three models in the range had now been fitted with independent front suspension.

The luxury version of the 402 was distinguished by the use of a new type of Cotal electrically controlled epicyclic gearbox, with direct drive on third and a geared-up top speed, plus a sunshine roof. The radiator grilles of the 1939 models were even more sharply raked, and the Airflow-inspired coachwork even more exaggerated in appearance. Highlight of the range was the new economy Type 202 - it was cheap enough to boost sales in the last year of peace to 52,796 cars, bringing Peugeot up into second position in the French motor industry, behind Citroen.

The Post War Peugeot Type 203

The war years saw a number of electric cabriolets constructed under the VL V model name and, when peace came, Sochaux was quickly back in production with the popular 202, of which 14,000 were delivered in 1946. The following year saw the introduction of a new model, the Type 203, with coil suspension all round (independent at the front) and a wet-liner 1·3-liter engine. Pre-war features which were retained were a geared-up top speed (although the gearbox was now of conventional design) and the option of a sunshine roof, while rack-and-pinion steering and hydraulic brakes were new features.

The Peugeot 404

The 203 was Peugeot's front-line model from 1949 to 1954, and achieved new sales records; it survived in production until 1960. In 1950, Peugeot swallowed

Chenard-Walcker and then also owned a sizeable lump of

Hotchkiss. Another best-seller appeared in 1955 - the 1·5-liter Type 403, an up-market model which sold a million between its introduction and April 1962, acquiring along the way the option of the power unit of the 203 when that model was finally pensioned off in 1960, and, from 1959, the option of an Indenor diesel engine. As far as styling went, the 404, launched in 1960, was the same bland Farinaceous mixture as the superficially similar BMC ASS and Fiat 1800/2100 ranges, with squared-off coachwork and vestigial tailfins. It had an enlarged 1618cc version of the 403 engine tilted at 45 degrees and MacPherson strut independent front suspension; it was a tough model which enjoyed considerable success in the East African Safari, an event which earned a considerable amount of prestige for Peugeot.

The end of 1962 saw the introduction of wagon versions of the 404, either with the 1468 cc engine from the 403 or the 1618cc unit. Family wagons were available with an extra rear bench seat to increase the carrying capacity to eight people. Kugelfischer fuel injection was optionally available on coupe and cabriolet versions of the 404, while a fuel-injected sedan appeared in 1965. In 1965, a new small Peugeot, as technically advanced as the 404 was orthodox, made its appearance. This was the Type 204, a four-door saloon with a transverse 1130cc all-aluminum sohc engine which drove the front wheels through a four-speed all-synchromesh gearbox located in the sump. It was independently suspended all round. Styling, by Farina again, was far sleeker than the 404.

The Peugeot 304

The 1970 304 was an enlarged, 1288cc version of the 204 with distinctive trapezoidal headlights, a feature shared with another new model, the top-of-the-range 504, similarly styled, with a 1796cc ohv wet-liner engine developed from the 404 power unit. Servo-assisted disc brakes were fitted all round. Swept volume of the 504 engine was raised to 1971cc in mid 1970. Meanwhile, Peugeot had been making some alliances: in 1964 there was a pooling of some resources with Citroen, one result of which was either marque taking a half-share in the Indenor diesel-engine factory. Then, in 1966, came a joint research development and investment programme between the still family controlled Peugeot empire and the state-owned Renault company.

One recent result of this was the 2664cc V6 all-aluminum engine announced at the 1974 Paris Salon. A third party to this particular development was the Swedish Volvo company, all three marques having taken shares in the financial and technical expenses involved. In the Peugeot application, in the 504 coupe and convertible, the V6 had an electronic ignition system which dispensed with conventional contact breakers, and an ingenious twin-carburetor unit supplying a common plenum chamber. The idea behind the carburetor was that the forward carburetor unit was a single-choke instrument mechanically linked to the throttle pedal. Once this carburetor was half open, depression in the plenum chamber caused the rear, twin-choke unit to open, it being operated by vacuum only.

The Peugeot V6 504

For the first time on any Peugeot model, the V6 504 derivatives had power-assisted steering. At that same 1974 Salon, a proposed merger with Citroen, which had been rumoured for some time, became more concrete. It was announced that Peugeot would be taking over 50 per cent - and management control - of the ailing Citroen company. Because, unlike most of the European motor industry, Peugeot managed to weather the economic storms of early 1975 with increased sales revenue. Although home sales fell by 12 per cent, export sales were up by 29 per cent, resulting in net sales of 3.1 billion francs, a 40 per cent increase over the corresponding period of 1974. Output, however, was 4.3 per cent down, at 188,000 cars, compared with 196,000 for the same quarter of the previous year, although the company had managed to avoid short-time working.

During the mid 1970's over one-third of Peugeot production was of the 504; 20 percent of total output was diesel-engined, reflecting an interest in the compression-ignition engine dating back to the 1923 Peugeot-Tartrais car. In August 1975 the Peugeot company launched their new top-of-the-market car, the V6 604 Saloon. This model was somewhat hastily unveiled at the Geneva Show the previous spring as Press leaks had revealed its existence. In 1977, Peugeot launched the 305, which was surprisingly BMW-like in appearance. It was, of course, front-wheel drive and was available with either 1300 or 1500cc ohc engines. It was based on Peugeot's VSS safety vehicle with bolt on wings, deformable structures and reinforced doors, and yet was no longer than the 304. Suspension was all-independent by MacPherson struts at the front and trailing arms at the rear.

Taking Over The European Division of Chrysler

Peugeot took over the European division of Chrysler (which were formerly Rootes and Simca), in 1978 as the American auto manufacturer struggled to survive. Further investment was required because PSA decided to create a new brand for the entity, based on the Talbot sports car last seen in the 1950s. From then on, the whole Chrysler/Simca range was sold under the Talbot badge until production of Talbot-branded passenger cars was shelved in 1987 and on commercial vehicles in 1992. The flagship of this short-lived brand was the Tagora, a direct competitor to PSA's 604 and CX models. This was a large, angular saloon based on Peugeot 505 mechanicals.

But all this investment caused serious financial problems for Peugeot; PSA lost money from 1980 to 1985. The Peugeot takeover of Chrysler Europe had seen the aging Chrysler Sunbeam, Horizon, Avenger and Alpine ranges rebranded as Talbots. There were also new Talbots in the early 1980s—the Solara (a sedan version of the Alpine hatchback), and the Samba (a small hatchback to replace the Sunbeam). In 1983 Peugeot launched the popular and successful Peugeot 205, which is largely credited for turning the company's fortunes around.

The Talbot Name Is Dropped

In 1986 Peugeot finally dropped the Talbot marque when it ceased production of the Simca-based Horizon, Alpine and Solara models. What was to be called the Talbot Arizona became the 309, with the former Rootes plant in Ryton and Simca plant in Poissy being turned over for Peugeot assembly. Producing Peugeots in Ryton was significant, as it signalled the very first time Peugeots would be built in Britain. The Talbot name survived for a little longer on commercial vehicles until 1992 before being shelved completely.

As experienced by other European volume car makers, Peugeot's U.S. and Canadian sales faltered and finally became uneconomical, as the Peugeot 505 design aged. For a time, distribution in the Canadian market was handled by Chrysler. Several ideas to turn around sales in the United States, such as including the Peugeot 205 in its lineup, were considered but not pursued. In the early nineties, the newly introduced Peugeot 405 proved uncompetitive with domestic and import models in the same market segment, and sold less than 1,000 units. Total sales fell to 4,261 units in 1990 and 2,240 through July, 1991. This caused the company to cease U.S. and Canada operations after 33 years.

Beginning in the late 1990s, with Jean-Martin Folz as president of PSA, the Peugeot-Citroën combination seems to have found a better balance. Savings in costs are no longer made to the detriment of style. On April 18, 2006, PSA Peugeot Citroën announced the closure of the Ryton manufacturing facility in Coventry, England. This announcement resulted in the loss of 2,300 jobs as well as about 5,000 jobs in the supply chain. The plant produced its last Peugeot 206 on December 12, 2006 and finally closed down in January 2007.

Also see: Peugeot Car Reviews