|

Mercedes-Benz

|

1926

- present |

Country: |

|

|

Daimler-Benz AG was an amalgamation of two fii:ms that created the motor car and the industry that eventually grew up around it. Gottlieb Daimler was born in 1834 and in 1872 he became technical director of the Deutz gas engine factory, where the chief designer under him was Wilhelm Maybach.

The two were a very effective team. Daimler, systematic, thorough, and inventive, was the creative man; Maybach, with his genius in putting an idea into practice, was the interpreter, though not to be denied his own inventive ability.

The starting point of these two men on the road to modem petrol engines and cars was the Otto four-stroke gas engine of 1876, which Deutz built commercially; and so the internal combustion engine (discounting such earlier dead-ended examples as the 1863 Lenoir) virtually grew up in their hands.

By 1882 Daimler had decided that what was needed for vehicle propulsion was a petrol engine much lighter in weight and much faster in crankshaft speed than the ponderous industrial engines of the time; and together with Maybach, he left Deutz, in order to embark on the new venture.

The following year he succeeded in building a high-speed engine suitable for vehicle propulsion, and within another two years it had been developed far enough for installation in a motor cycle (a bicycle test-bed with two small outrigger wheels) which Maybach successfully rode to open a new era.

In 1886 the new engine was put into a four-wheeled vehicle (and also into a motor boat) - though it was not strictly a car as we would define it today, rather a converted horsedrawn carriage in which the drive from the engine to the rear wheels was by a selection of belts to a countershaft with gear drive to the wheels themselves.

Daimler was not obsessed with the idea of the motor car. He was far more ambitious than that, conceiving his engine as a propulsive unit for boats, fire engines, airships, and large commercial vehicles for the carriage of freight or passengers. Only about 60 miles away from his Cannstatt factory, in Mannheim, worked a less easily distracted pioneer, Karl Benz. He was Daimler's junior by ten years (and was to survive him by 29) and in 1877 he began to design a two-stroke gas engine that he hoped might rival the quickly-established four-stroke of Otto.

He had a hard time of it, but in 1882 successfully patented a two-stroke that was significantly more efficient than others. Two years later, the validity of Otto's patent began to appear questionable, and Benz felt free to develop a four-stroke engine in which he embodied some of his best previous work; and in the winter of 1885/6 he designed and built his first car. Unlike the prototype Daimler, the first Benz depended little on horsedrawn carriage practice but was an integrated design, in which the disposition of the engine, with its large slow-running flywheel turning about a vertical crankshaft axis so as to minimise the danger of gyroscopic precession when turning corners, was as significant an improvement on earlier ideas of a mechanically propelled vehicle as the power of the engine was a significant pointer to the performance that might be expected.

It wasn't the fast-running lightweight that Daimler envisaged; but even at 250 or 300 rpm, it was fast by the standards of its time, and later tests in Stuttgart Technical College showed that it could run at 400, half the crankshaft speed of the Daimler. Relatively slow, heavy and not terribly efficient, the Benz engine was nevertheless probably the more manageable of the two and, from the very beginning, Benz insisted on electrical ignition, troublesome though it was in those early days, whereas Daimler relied upon the hot tube system that made refinement of running impossible to achieve.

The Victoria Four Wheeler

The objectivity and practicality of his design gave Benz an early lead in the industry; after making a couple more three-wheelers like his 1886 prototype, and after patenting some good ideas such as a fireproof carburetor (Maybach's spray-type carburetor for Daimler had already established itself as a rival attraction) he began to sell cars in 1888, and soon had 50 men employed making more. In 1893 he produced a four-wheeler named the Victoria, with a 3 hp engine of 2.9 liters displacement, a vertical flywheel, a float-fed carburetor, and an ignition timing control which enabled a more flexible performance to be achieved than ever before.

Mercedes Jellinek.

Mercedes Jellinek.

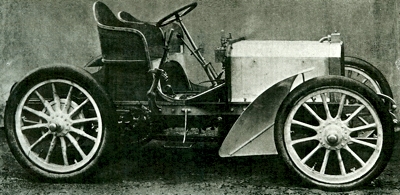

The first Mercedes, built in 1901, and designed by Wilhelm Maybach.

The first Mercedes, built in 1901, and designed by Wilhelm Maybach.

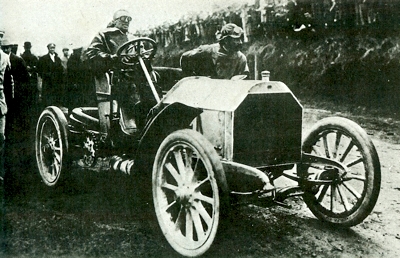

1904 Mercedes Simplex Rennwagen 60PS competing in an early motor race. The car was chain driven, as were all Mercedes until 1909.

1904 Mercedes Simplex Rennwagen 60PS competing in an early motor race. The car was chain driven, as were all Mercedes until 1909.

A 4.5 Liter Mercedes pictured during the 1922 Targa Florio.

A 4.5 Liter Mercedes pictured during the 1922 Targa Florio.

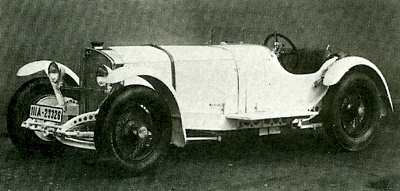

1927 Mercedes-Benz S26/120/180 PS, powered by an inline six cylinder 6.8 liter engine.

1927 Mercedes-Benz S26/120/180 PS, powered by an inline six cylinder 6.8 liter engine.

1931 Mercedes-Benz SSKL, powerec by a 7.1 liter six-cylinder engine developing 300 bhp.

1931 Mercedes-Benz SSKL, powerec by a 7.1 liter six-cylinder engine developing 300 bhp.

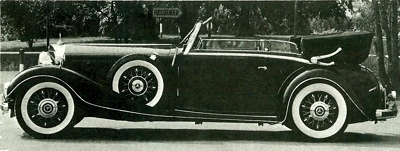

1930's Mercedes-Benz 500.

1930's Mercedes-Benz 500.

Caracciola's SSK in action during the 1930 Mille Miglia.

Caracciola's SSK in action during the 1930 Mille Miglia.

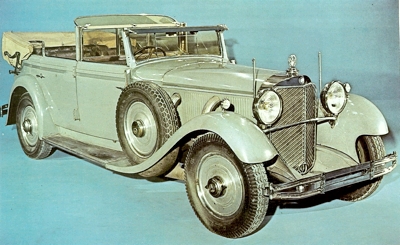

1930 Grosser Mercedes 770, which was fitted with a 7655cc 150bhp in-line six.

1930 Grosser Mercedes 770, which was fitted with a 7655cc 150bhp in-line six.

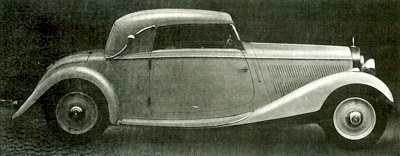

1932 Mercedes-Benz Cabriolet, which was fitted with a 1962cc 40bhp engine giving the car a top speed or around 100 kph.

1932 Mercedes-Benz Cabriolet, which was fitted with a 1962cc 40bhp engine giving the car a top speed or around 100 kph.

1932 Mercedes-Benz Mannheim Sport, which was fitted with a 3663cc 75bhp engine and a top speed of 120 kph.

1932 Mercedes-Benz Mannheim Sport, which was fitted with a 3663cc 75bhp engine and a top speed of 120 kph.

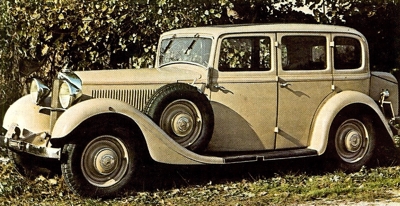

1934 Mercedes-Benz 290, which was fitted with a 2867cc six cylinder engine developing 68 bhp at 3200 rpm. It had a top speed of 110 kph.

1934 Mercedes-Benz 290, which was fitted with a 2867cc six cylinder engine developing 68 bhp at 3200 rpm. It had a top speed of 110 kph.

It looks a little weird doesn't it? The engine looks like it has two ends, and was designed during the 1930's as the model 130H, with the engine hanging over the rear wheels.

It looks a little weird doesn't it? The engine looks like it has two ends, and was designed during the 1930's as the model 130H, with the engine hanging over the rear wheels.

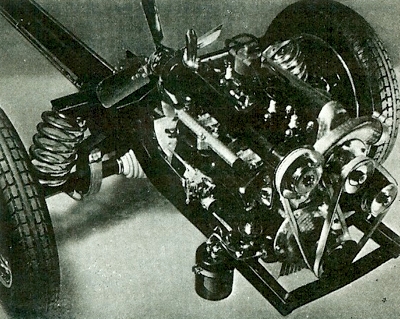

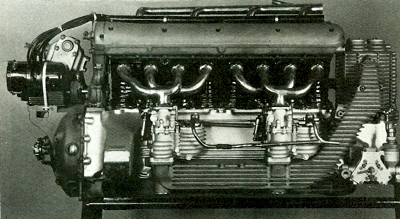

This rare image is of the 1934 W25 Grand Prix Car's engine. A supercharged straight-eight developing 354 bhp from its 3.36 liters. The cylinder head had twin overhead camshafts.

This rare image is of the 1934 W25 Grand Prix Car's engine. A supercharged straight-eight developing 354 bhp from its 3.36 liters. The cylinder head had twin overhead camshafts.

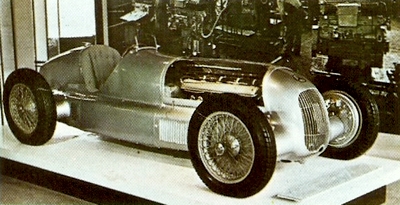

Mercedes-Benz W25 Grand Prix car, blindlingly fast on the straights but not so good around corners.

Mercedes-Benz W25 Grand Prix car, blindlingly fast on the straights but not so good around corners.

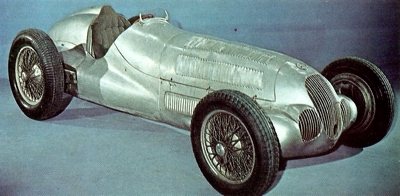

1937 Mercedes-Benz W125, producing 646 bhp and capable of a genuine 200 miles per hour. The wheels would still be spinning at 150mph in top gear.

1937 Mercedes-Benz W125, producing 646 bhp and capable of a genuine 200 miles per hour. The wheels would still be spinning at 150mph in top gear.

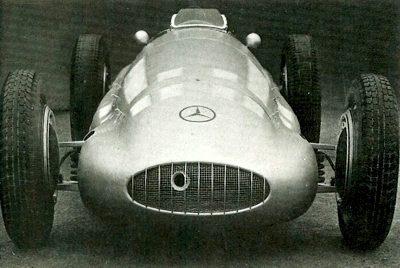

The 1938 W154 3 liter V12 evolved into the W163, developing 483 bhp and capable of 195 mph.

The 1938 W154 3 liter V12 evolved into the W163, developing 483 bhp and capable of 195 mph.

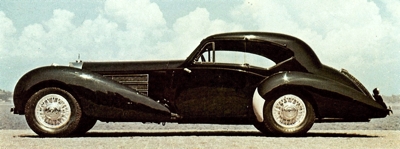

Mercedes-Benz 540K.

Mercedes-Benz 540K.

1949 Mercedes-Benz 170S, which was fitted with a side-valve four cylinder engine developing 52 bhp.

1949 Mercedes-Benz 170S, which was fitted with a side-valve four cylinder engine developing 52 bhp.

1954 Mercedes-Benz 300 Limousine.

1954 Mercedes-Benz 300 Limousine.

Stirling Moss in a W196, who one only 1 GP with thes car. Fangio, on the other hand, managed 9 wins in the W196.

Stirling Moss in a W196, who one only 1 GP with thes car. Fangio, on the other hand, managed 9 wins in the W196.

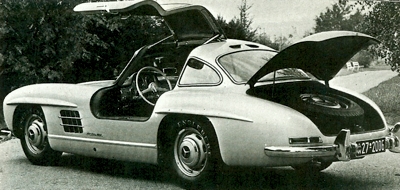

Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing.

Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing.

1959 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Roadster.

1959 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Roadster.

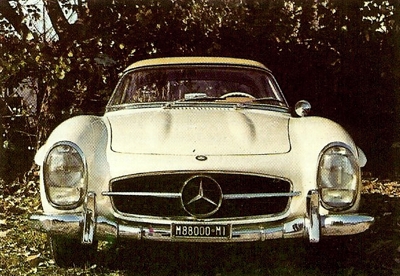

1956 Mercedes-Benz 190SL.

1961 Mercedes-Benz 300SE, derived from the 220 of 1959. It was fitted with a 2996cc six cylinder engine developing 170 bhp.

1963 Mercedes-Benz 230SL, which would morph into the 250SL and finally the 280SL.

1968 Mercedes-Benz 220D, popular as a taxi.

The mighty 350SL, which replaced the 280SL.

Mercedes-Benz W123 Series 280E, taking its styling from the older S class cars.

1977 Mercedes-Benz S Class Wagon.

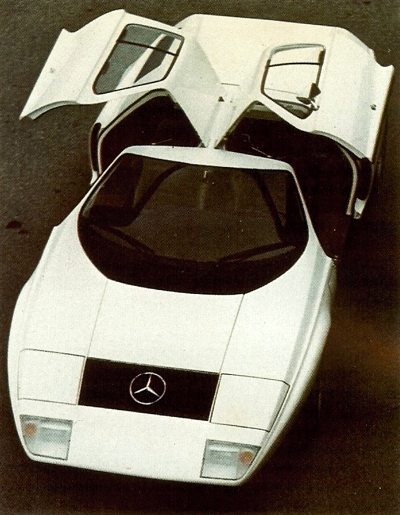

Mercedes-Benz C111, which was fitted with a three-rotor Wankel engine. It developed 280 bhp, driving the rear wheels through a ZF gearbox, giving it a top speed of 190 miles per hour. MB management, unfortunately, decided against putting the car into production. |

The Victoria and its derivatives remained in production for a long time. It was preferred by many for the ease of changing speed, this being done by a system of sliding drive belts over fast and loose pulleys on a countershaft, which was a quieter and more painless procedure than went with the mechanical gearboxes of the many cars springing up in the image of the 1891 Panhard.

That pioneering French car (originally powered by a V-twin Daimler engine such as by then featured in the Cannstatt machine) was very influential in determining the morphology of the modern motor car. Instead of being a motorised horse-drawn carriage, it had a chassis with a front-mounted engine and a drive line arranged in a way that would be recognisable as a car even today, and before long Daimler was on the same track.

His 1894 Vis-a-Vis with its two-cylinder 3½-horsepower engine showed a trend towards the new proportions, and in 1897 the Daimler Phonix with a twin-cylinder engine under a front bonnet confirmed it. Benz, initially the more creatively adventurous, now subsided into a stubborn conservatism, doubtless born of the hardship that wearied him in the previous decade.

The World's First Production Car - The Benz Velo

He stuck to his established patterns, doing no more than evolve a smaller vehicle similar to the Victoria, but adapted for quantity production with a little 1½-horsepower single-cylinder engine. This was the Velo, the world's first production car; it accounted for most of the production of 67 Benz cars in 1894, a figure that grew to 135 in the following year and 181 in 1896.

By this time Benz could afford to be a little more adventurous, and produced his Kontra-Motor, an engine with two horizontally opposed cylinders, popularly called the Dos-a-Dos. He expanded production to include a truck, and by 1898 was so far advanced he decided to adopt pneumatic tyres for a car that was then proclaimed the Benz 'Comfortable'.

By 1899 production neared 600 cars, and Benz even built a 12 hp racer. It hardly compared with the coeval racing Daimler Phonix, Daimler had been making design changes all the time, keeping himself up to date, adopting new ideas such as the Bosch magneto, together with chain drive and all the other features evolved from the epoch-marking Panhard.

Defining The Modern Motor Car

When he died in 1900 the Daimler company was just on the verge of producing something even more definitive than the French pioneer; and in 1901 Daimler's surviving partner, the redoubtable Maybach, produced the car that in one clean sweep defined the modern motor car as we broadly know it today.

Instead of a wooden chassis with flitch plates, it had pressed-steel chassis members; instead of a troublesome and imprecise quadrant gear shift, it had a gate change allowing any ratio to be selected at will and without much difficulty. It had a beautiful and very efficient honeycomb radiator in place of the grotesque lengths of finned tube that had been been used before; and its four-cylinder 35-horsepower engine was the first to have mechanically operated inlet valves (instead of the automatic type) with a variable lift device giving the driver an additional means of control over the engine speed.

It was a brilliant new car, quieter and more flexible and altogether better mannered than anything previously known, and more completely definitive in its design than anything to follow for at least half a century; and for reasons that were hardly made clear at the time, and continued to cause some confusion for ages afterwards, it was called the Mercedes.

The Gentleman with the Girl's Name

The name had been seen in association with Daimler cars already. In 1897 it had been used as a pseudonym by a wealthy gentleman entering a Daimler Phonix in the motor-sport events of the Nice week. The "gentleman with the girl's name" was Emil Jellinek, a wealthy fruit importer who, not wishing to follow in the footsteps of his father (a Rabbi in Leipzieg) embarked on a life of adventure and trade in the course of which he acquired a beautiful Spanish wife, two pretty daughters, a sizeable fortune, and such standing among the aristocracy that by 1900 he was appointed the Austro-Hungarian Consul in Nice.

Jellinek had also become a great motoring enthusiast, and was very taken with the Daimler Phonix that he chose to drive quite successfully at Nice. His pseudonym was actually the name of his elder daughter - and when he sought the concession for selling Daimler cars in France, Austria, Hungary, Belgium and the USA, the name came in handy again: legal difficulties with Panhard et Levassor, who claimed the sole right to sell Daimler cars in France, prompted the idea that the new Maybach model should be called simply the Mercedes.

After a team of the cars was taken to Nice, completely devastating the opposition in 1901, the name was firmly established. So began an era during which the Mercedes went from strength to strength under the technical direction of Maybach and incidentally with Jellinek on the Board. These two were both keen on racing, and made it pay: when the specially prepared team of racers for the 1903 Gordon Bennett race was destroyed by fire, standard production Mercedes specially tuned to develop 60 horsepower were rushed to Ireland for the race, and won it.

Benz built a 60 horsepower racer that year too, naming it the Parsifal, and it was undoubtedly fast; but in general he clung to his old models, and while the Mercedes was in the ascendant the Benz began to decline. By 1908 the Mercedes racing organisation was developed to a fine pitch. They had already introduced tactics and strict discipline in the 1907 Grand Prix, the crews attending lectures in which they were instructed not only in the niceties of their machines and the circuit layout, but also on the features whereby they might recognise their rivals on the road, and even the weaknesses and foibles of rival drivers, with hints on how these might be exploited.

Mercedes vs. Benz

For the 1908 race attention to detail went as far as the provision of compressed-air quick-lift jacks for wheel changes at the pits-but it was the cars themselves which were most notable of all. This was a year in which racers were subjected to regulations governing not only weight but also piston area, so that most of the contenders had four-cylinder engines displacing 12.83 liters, including Mercedes.

But what set the Mercedes apart was that, although the engine was generally unremarkable, it was mounted in the chassis in such a way that it offered a new refinement, giving roadworthiness and liveliness that were exceptional. The engine, already smaller and presumably lighter than the gigantic monsters of previous years, was mounted further back in the frame so as greatly to improve what had previously been an excessively nose-heavy weight distribution.

The huge flywheel, a characteristic feature of the time, the 550 millimetres diameter being necessary to ensure the smooth operation of of such a large and slow-running an engine, was mounted well back from the main mass of the engine, so as to be just about at mid-wheelbase; and the gearbox and bevel housing and final chain drive, all located after this flywheel beneath the floor, directly below where the driver and mechanic rode.

Polar Inertia

In those days it was virtually impossible to have a racing car perfectly balanced with 50/50 weight distribution, but the Mercedes design ensured a large proportion was over the rear wheels, and there was enough in the middle to provide a low polar moment of inertia. In this chassis, perhaps for the first time in racing, we see a deliberate policy being applied to polar inertia which, when minimised, gives the car very prompt steering and agile handling.

The virtues of this chassis were displayed by its setting up a new lap record from a standing start in practice before the -race, the speed being 4% higher than the record established by a 17.3-liter Dietrich in the previous year. After a cautious and disciplined drive in the race, with Lautenschlager at the wheel, the Mercedes won the 1908 Grand Prix; but the honour of Benz was far from being disgraced, securing second, third, fifth and seventh places. In fact the quality of Benz manufacture was being well maintained, and if sales were not rocketing the firm was doing good enough business, with a lively racing programme playing an important part in publicity.

The 22-Iitre Blitzen Benz

Numerous successes in European and American racing led to a series of attacks on world records with some really 'Big Bangers', culminating in the 200 horsepower 22-Iitre Blitzen Benz. This was built in 1909 to a design instigated by Victor Hernery, who had driven the second-place Benz in the 1908 GP and worked closely with Karl Benz. His object was to be the first to achieve 200 kilometres per hour, and the car was built with all the attention to streamlining, minimal frontal area, maximal weight saving, that could be imagined at the time.

At

Brooklands it reached a shade over 127 mph (205.7 kph) over the half-mile and thus established a world record. At Brussels it reached 115.4 kph over a kilometre from a standing start. At Daytona Beach in Florida in 1910,

Barney Oldfield managed 211.4 kph over a mile, and a year later pushed the figure up to 228.1 (141.42 mph), a world record that was to remain unbeaten until 1924.

Meanwhile there were some important changes taking place at Stuttgart whither the Daimler firm had moved in 1903. In 1907 Maybach had left the company to found a firm of his own specialising in aero-engines, and his place as chief engineer and designer was taken by the founder's son, Paul Daimler, who had been at Austro-Daimler (a firm in which Jellinek also had an interest).

The Three-Pointed Star

After his accession most Mercedes cars acquired shaft drive instead of chain, and in 1909 a licence was taken for manufacture of Knight sleeve-valve engines, which remained in production until 1923. Also in 1909 the company applied for registration of the now famous three-pointed star as a Mercedes trade mark, and began using it regularly.

Daimler were flourishing, beyond doubt, with well-developed interests in every kind of mechanically propelled vehicle including aircraft, airships, railcars, boats, trucks, buses etc. They were all Daimlers, apart from some aero-engines; but the cars were now definitely Mercedes, and they had one more outstanding contribution to make to the history of motoring before World War 1 diverted the company's priorities elsewhere. This was in the Grand Prix of 1914, a year in which the principles expounded by Henry and his disciples working for Peugeot for the past three years promised to be vindicated even more thoroughly.

These ideas, based on the cult of efficiency and the pursuit of lightness, were turned against Peugeot by Mercedes, It was yet another example of a highly disciplined approach to the sport, but again the cars themselves were exemplary in overall concept and detail execution. The relatively small high-speed engine, now constrained by regulations to displace no more than 4.5 liters, gave these cars a higher performance than anything that had previously been seen in Grand Prix racing.

The engine of the Mercedes, based on aviation experience which conferred on it notably reliable cooling and modest weight, was also more robust, (particularly within the crankcase) than those of its French rivals; and if its power was not yet as great as that of the 12.8-liter Mercedes that had applied 135 bhp to the winning of the 1908 Grand Prix, the slight deficit of 20 horsepower was more than compensated by the reduction in frontal area achieved by the new feature of a double-dropped chassis frame, lowering the entire superstructure.

The driver's head was now less than five feet above the ground; he sat in the car, not on it, and the mechanic riding with him tucked himself away as much as was consistent with the operation of the elegant little pump w.ithwhich he pressurised the fuel tank on which it was mounted. The fine execution of such details was just a visible reminder of incredible devotion to detail in more important components; for example, the rear axle was constructed so as to set the driving wheels perpendicular to the surface of the cambered roads on which the 1914 race was run, and for the sake of reliability each half-shaft was made integral with its own crown-wheel gear.

Every feature of the course, of the opposition, and of the car itself, was subjected to exhaustive scrutiny by the Mercedes racing department, so it was as much due to strictly disciplined team control, effective signalling, and outstanding reliability, as to the sheer speed of the cars, that Mercedes swept- to a 1-2-3 victory, reaching speeds as high as 115 mph, for the first time in racing of this class.

There remained only one sign of weakness, the 1914 Mercedes was the last car to win a proper Grand Prix with a front axle devoid of brakes. At Indianapolis, where brakes were irrelevant, the car won in 1915. Far more radical things were to appear after the war. Benz, learning that suitable injection apparatus had at last been evolved by the Swiss engineer Leissner, returned to the diesel engine ideas that they had been working on in 1909, and patented a new form of pre-combustion chamber for small high-speed diesels.

Benz-Sendling Agricultural Tractors

The first examples of the engines embodying this patent were fitted to Benz-Sendling agricultural tractors, and proved so successful that production was immediately expanded to include a 50-horsepower engine for a five-ton truck, which attracted tremendous praise when shown at Amsterdam in 1924. This development did a great deal to popularise the diesel commercial vehicle, and later the diesel-engined private car, and the success of the pre-combustion chamber encouraged numerous firms in Germany and elsewhere to acquire licences for its manufacture.

On the car front Benz remained staunchly conservative for a while, providing the heavy touring cars that they were developing when the war broke out, and at the same time gathering some welcome racing successes with the very pretty 10/30 model, a kind of miniature Blitzen with a sharp Mercedes-style radiator.

In 1923, however, they fielded at Monza for the second Grand Prix of that year a pair of quite revolutionary cars. So far as the two-liter engines were concerned, they were merely copies of the six-cylinder GP Fiat of 1922, as indeed were most rivals; but in every other respect resemblance to anything else was undetectable.

The Benz Tropftoagen

Known as the Tropftoagen, this Benz had a body of circular cross-section and academically streamlined profile, its lines interrupted only by the cockpit opening and the cowled radiator behind. Within the shell lurked the promise of a revolution which was to be long in coming; in a configuration expounded by the aeronautical engineer Dr Rumpler, the engine was located behind the driver, communicating through a three-speed gearbox to a bevel housing that was fixed to the chassis and was flanked by the brakes, outboard of which were pivoted swinging half-axles that gave the car the first independent rear suspension of any racer.

It was an isolated experiment that was crowned with less success than it perhaps deserved, either as a single-seater racer or as a two-seater sports car, though it was driven with some success in hill-climbs and other events by the adept Rosenberger, who was later to encourage Ferdinand Porsche to design a similarly rear-engined GP car for Auto Union a decade later.

The 1921 Berlin Motor Show

In 1922 Porsche moved from Austro-Daimler to Mercedes as chief engineer and designer, taking the place vacated by Paul Daimler. There he inherited yet another revolution that began in 1915 with work on supercharged aero-engines. The first production cars to be fitted with superchargers appeared at the Berlin Motor Show of 1921, a 1½-liter and a 2.6-liter Mercedes.

It would take another two years before forced induction would make its appearance in Grand Prix racing, but in 1921 Mercedes were offering it on road cars, in a refined arrangement that allowed the supercharger to be cut in or disconnected at will by the driver kicking down or releasing the accelerator pedal accordingly, when a clutch would act appropriately in the drive to a Roots. supercharger that fed compressed air to the carburetors - a highlight was the highly idiosyncratic noise.

In 1922 another pair of blown Mercedes were marketed, this time six-cylinder machines of four and six liters displacement. Inevitably the competition cars had to follow suit, and a group of two-liter designs - the first with four cylinders, the second with eight - were raced everywhere possible. The straight-eight was very fast and difficult to manage, but the four was a very effective machine and scored a double victory in the Targa and Coppa Florio races of 1924.

Mercedes and Benz Scored 293 Victories

That was a year in which Mercedes and Benz cars between them scored no less than 293 victories in assorted competition events, but the victories were Pyrrhic. Times were very hard, especially for motor manufacturers in Germany-and at that time there were 86 different companies in the country producing between them 14,4. different models. There was a luxury tax of 15% on the purchase price; to make things more difficult, import duties had been drastically cut so that foreign cars flooded on to the German market.

In view of the. poverty spreading through Germany as a result of the war, of the crippling demands of the victors for reparations, and of the ensuing inflation, one single factory would have sufficed to supply the whole of the German market. Accordingly, Benz & Cie and the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft entered into an association of common interest that led to a complete amalgamation and the constitution of the new Daimler-Benz AG, at the end of June 1926.

Already, other manufacturers had sought to survive by cutting prices and cheapening their products; but they failed, and these failures confirmed Daimler-Benz in their determination to maintain the high standards that had always distinguished their work. To serve as a reminder of those traditions, the new Mercedes-Benz badge embodied the Mercedes three-pointed star, encircled by the Benz laurel wreath.

The Mercedes-Benz Stuttgart and Mannheim

Apart from the commercial vehicles and the ante-chamber diesel (the latter proving to be an important asset), production was concentrated on the heavy but flexible 16/50 Benz and the supercharged Mercedes. New 1926 models were a pair of heavy side-valve six-cylinder tourers, the two-liter known as the Stuttgart and the 3. 1-liter known as the Mannheim because they were built in those factories respectively.

The 4.6-liter straight-eight was added in 1928, and the existing six-liter supercharged Mercedes design dating from 1922 was developed into the sports model K with shortened wheelbase and engine enlarged to 6½ liters to give 110 horsepower without the blower engaged, or 160 when supercharged. This was the fastest touring car of its kind on the world market, and sired a line of immensely successful big high-performance cars that were to keep the firm's reputation alive in racing through the difficult years of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The Mercedes-Benz SS, SSK and SSKL

The 6.8-liter S type 36/220 was a long and relatively low four-seater of rakish lines and blistering performance, nowhere near as heavy as it looked because the huge cylinder block was a light-alloy casting, and nowhere near as clumsy as it looked because the steering geometry was superb and the controllability of the car exceptional. From it came the 7.1 liter SS, the short chassis SSK, and finally the ultra-sporting and drastically lightened SSKL.

They were not racing cars, but there were many occasions when stripped versions of these big tourers and sports cars not only provided a useful leavening of the field but also threatened opposition that the driver of a thoroughbred racing car might despise at his peril. It was perhaps not unreasonable that they should win the Ulster TT in 1929, the Irish Grand Prix in 1930, and even the

Mille Miglia in 1931; but it was remarkable that in 1928 one of these monsters managed to finish third in the German Grand Prix at the Niirburgring behind two Bugattis, and won against similar but suitably faster opposition in 1931.

Even more astonishing, back in 1929, by the most convincing display of driving virtuosity as well as of mechanical stamina, that outstanding Mercedes-Benz driver Rudolf Caracciola finished the Monaco Grand Prix in third place in an SSK, a position he was holding again in the same fiendishly twisty race in 1931 when clutch slip forced his retirement.

It was hardly surprising that by 1931 the SSKL should be competent to dominate the Avus races, which put a premium on speed and discounted everything else, by then the power of this car was near 300 bhp, so that it must have profited from a ratio of about 17 horsepower per square foot of frontal area to reach an appreciably higher maximum speed than, say, the type 3SB Bugatti which had only 10.8.

The Mercedes-Benz Model 170

Nevertheless, the directors judged it prudent to withdraw from racing for a while, while they entered the economy market with the six-cylinder 1.7-liter model 170. This was the first Mercedes-Benz to have independent suspension, by double transverse leaf springs at the front and by helically sprung swinging half-axles at the rear. This car was a landmark in the company's history, being full of technical niceties. The chassis was built up from box-section members instead of the traditional channels, the gearbox had an overdrive top speed, all four brakes were hydraulically operated, there was centralised chassis lubrication, thermostat control of engine cooling, and great general attention paid to structural stiffness, from the short-spoked wheels to the extensive bracing of the chassis.

Wishbones and helical springs replaced the transverse leaves on the blown straight-eight derivative that appeared in 1933 as the model 380, confirming a system of type numerology begun with the 170, in which the number nearly always identified the engine capacity in liters. The next model to appear was the 130H, which was obviously of 1.3 liters displacement and the H (for Hintern) demonstrated that the engine was in the rear. Here was revolution indeed, even though it was not home-grown but had come from the Czechoslovakian work of that clever Tittra engineer Ledwinka.

The 130H had, like Ledwinka's cars, a large-diameter tube as a backbone constituting the chassis, with cross members front and rear carrying the independent suspension and the steering and propulsive units. The engine was a rubber-mounted side-valve four, in unit with a transmission that had an overdrive fourth gear that was semi-automatic as it could be engaged without using the clutch. The whole car was simple, neat, soundly made and sensibly proportioned, an outstandingly practical predecessor of the KdF Volkswagen that Porsche was later to produce.

The suspension geometry produced camber changes that might have inhibited high-speed cornering, but on the rough roads that abounded in many parts of Europe it gave a notably superior ride to anything that conventional cars could offer, and as an economy car it was not intended for sporting use anyway. This did not stop the firm from adding to the range, a two-seater version with an - overhead-camshaft engine giving 55 bhp, later in 1934.

The Mercedes-Benz 170V

Perhaps unfortunately, Mercedes-Benz were uncertain about the reception the rear-engined cars would receive from the public, and so they simultaneously developed a new front-engined car; and this, the 170V (Vor, meaning the opposite of Hintern) was so successful that the rear-engined car was soon ousted. Coming on the market in 1936, the 170V was a lightweight (13 cwt) 38 horsepower all-purpose design that could carry a two or four-seater saloon, a delivery van or platform body or even an ambulance body on its beautifully shaped chassis, a cruciform type composed of oval-section tubes.

The 170V was not an expensive car, but it was inimitably refined in mechanical and bodily detail. It could reach 62 mph, cover 28 miles per gallon, ride as comfortably as almost anything on the market, and survive the rigours of the central European climate; and the sale of more than 90,600 examples up to the end of 1942 was evidence of the high esteem in which it was held.

Public respect for the abilities of Mercedes-Benz reached a new and all-time high level in the late 1930s. It was not the popular 170V that was entirely responsible, nor the similar but six-cylindered 290 - nor even the 500K and 540K supercharged coupes that grew out of the 280 chassis. It certainly was not the 7.7-liter Super or Grosser Mercedes straight-eight, a car seemingly built exclusively for wealthy industrialists or party leaders which remained classically conservative until 1937 and aggressively modem from 1938 when it acquired a low-built tubular chassis frame, independent suspension, and a five-speed synchromesh gearbox.

What really gave the company respect in their homeland was the return to top-class motor racing in 1934, when a new formula came into effect limiting Grand Prix cars to a dry weight (without tyres) of 750 kilogrammes, with no other restrictions imposed but a minimum width for the cockpit. This formula had been published in October 1932, shortly after which the directors of the company held a board meeting at which they discussed the design of a pure racing car with which to restate their interest in the sport.

State Motor-Sport Sponsorship

Obviously Mercedes-Benz engaged in motor-sport to demonstrate their technical superiority, but it remains a fact that the final decision to compete was taken in March 1933, and it was only during that year that Hitler finally came to power in Germany. He was already a confirmed and knowledgeable motor-racing enthusiast, so when his Nazi commissariat urged the German motor industry to play a vigorous part in the extension of German prestige abroad, and by their technical accomplishments to represent (or if you prefer, misrepresent) the beneficial consequences of adopting the National Socialist ideology, the encouragement was made manifest in the allocation of considerable sums of money.

There was plenty of prize-money put up for the most successful German racing car of 1934, and an annual subsidy provided to Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz was proposed. Even more important, in view of the very considerable sums that were soon to be lavished upon the cause (amounting to roughly US$500,000) they were allowed to offset their racing costs against re-armament contracts.

Dr Hans Niebel

To Mercedes-Benz, whose racing department had been feeling the pinch of the company's financial controllers as recently as 1931, such tangible encouragement was understandably welcome, leaving them to concentrate upon technical problems that only Auto Union would also have the temerity to approach. The technical direction of the Mercedes-Benz programme was led by Dr Hans Niebel, who had originally been with the Benz company before the amalgamation, assisted by another Benz inheritance in the form of Wagner who had been directly concerned with the 1924 racers.

A rear-engined car was discussed when the design of the new GP machine was being considered; but for a variety of good reasons, and some invalid ones, the idea was rejected - while Dr Porsche, now with Auto Union, embraced the idea with enthusiasm despite his background of front-engined racing cars and others designed during his time with Mercedes.

The car that the Stuttgart firm fielded in 1934 was the W25, which got the new formula off to an unexpectedly vigorous start with no less than 354 bhp from 3.36 liters. The engine was a supercharged straight-eight of fairly classical form, with two overhead camshafts and a one-piece crankshaft running in split roller bearings, with four valves seated in each combustion chamber, a Roots supercharger blowing into the carburetors, and a form of engine construction that could be traced back to the 1914 GP car, with forged-steel cylinder barrels and integral heads with welded-on ports and valvegear supports enclosed by thin sheet water jackets also welded on, the whole being light, strong, well cooled and tolerably stiff.

The chassis frame was simple, the suspension all-independent by methods already established in touring cars; there were large hydraulic brakes and some simple streamlining. Nevertheless the car gave trouble, the geometries of suspension and steering made it difficult to handle, and although it was blisteringly fast along the straights, it was not very good in corners. On its first appearance it was not even light enough to qualify for admission to the race, proving to be 1 kg over the limit. Every scrap of surplus metal having already been eradicated, there was nothing to do but to remove the paint, and the white cars reappeared the next day stripped of their coats and were weighed again in their bare burnished aluminum, when they were found to be 2 kg lighter!

When the engine displacement was increased later in the season, they lost a little more weight, and after a chequered season beset by teething troubles Mercedes-Benz emerged as the dominant make in 1935. The tables were turned in 1936 when Auto Union managed to increase their engine to a full six liters, developing 520 bhp, while the W25 Mercedes-Benz, enlarged by stages to 4.3 and then to 4.7 liters from which came as much as 494 bhp, suffered from the bad handling of a new short chassis and had a dismal year.

Rudolf Uhlenhaut

The remedial action taken by the designers, upon whom the brilliant young development engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut had an important and increasing influence, was epoch-marking. Extreme and extra-ordinary as the 1934 cars had seemed when they first appeared, they were surpassed by a generous margin in all respects by the W 125 car that was designed to carry the Mercedes-Benz star in Grand Prix racing for just one year, 1937, but to carry it honourably. This car mustered more power than any other Grand Prix racer before or since, obtaining it from an engine that was hardly at all unusual except in the superb workmanship and metallurgy that made its high performance possible.

As for the rest of the car, it showed scant respect for established motor-engineering practice: the chassis frame was made of thin-walled oval micro tubing, the springing was softer than any racing car had employed since the first decade of racing, the major components such as engine and transmission were arranged towards the extremities of the chassis so as to contribute to a high polar moment of inertia, and the elaborate fuel blend represented no less than a triumph of chemistry over the supercharged four-stroke cycle. Even the tyres, bearing the brunt of more than 600 bhp in a car whose mean racing weight was little less than a ton, had been studied with a far more scientific approach than they had ever before received, so that it became commonplace to see the technicians of Continental taking track temperatures before a race to decide on the appropriate inflation pressure for the huge nitrogen-filled tyres.

Only in one respect was the 1937 GP car noteworthy for its reversion to past practices, and by doing so it actually gained an enormous advantage over all its rivals, and set a new fashion that was to be followed by virtually every successful Grand Prix car until 1959. This was the de Dion rear axle, conceived and patented way back in 1892, arid subsequently ignored (save by Miller for Indianapolis racers) until ressurected for the W125. This form of suspension endowed the car with a combination of traction, cornering power, directional stability and immunity from torque reactions that was far in advance supplied the needs of its 646 bhp and 200 mph speed capability.

A powerhouse of a car, the W125 could spin its tyres on a dry concrete road at 150mph in top gear; although only Carraciola and a half-a-dozen other drivers were competent enough to exploit all its potential; nevertheless, in this inspired design Daimler-Benz enabled the chassis to catch up with more than 20 years of engine development. In the following year it was time for the engine to take its turn again. The new formula restricted supercharged engines to three liters displacement, which was supposed to reduce the speed of cars to much lower levels than had been achieved by the 5.7-liter straight-eight of the previous year.

To everybody's surprise the 1938 Mercedes Benz, numbered W154, had a V12 engine, recognising the emphasis laid by the new formula on the highest practicable rpm and the largest possible piston and valve areas. In its engine as well as in every other respect, the W154 was a good deal more complex than the essentially simple W125, though its constructional principles closely resembled it. It was a successful car, even though it was not as good as theoretical forecasts promised; but by the use of two-stage supercharging and some detail revisions to the chassis and body and especially to the brakes, the 1939 version (the W163) proved to be the fastest racing car yet seen.

With two superchargers in series pressurising its induction system to 2.65 atmospheres absolute, the 1939 car was given 483 bhp with which to urge its maximum laden weight of 1.2 tons at speeds up to 195 mph, while consuming expensive fuel at the unparallelled rate of about one mile per gallon. The fuel necessary to satisfy this thirst accounted for a quarter of the car's total weight on the starting line but it was weight that would be shed rapidly and to good purpose, so that the value of two-stage supercharging impressed itself so firmly on the motor-racing world that for more than a decade no proper Grand Prix car would be considered without it.

Once again Mercedes-Benz was in the vanguard of progress. Some of the make's foreign rivals resented this success, especially the Italians, who decided to play the game according to their own rules. They announced that for 1939 all major races in Italy would be for 1½-liter cars - and eventually it was made clear, as late as possible, that for the purposes of this argument Italy included the province of Tripolitania, where the Tripoli GP constituted one of the very fastest road races in the calendar.

Six months was the notice the Germans had of this trick; but it was all Daimler-Benz needed. The consternation of the Italians was almost comical, what was to have been their own private race was invaded by a pair of brand new 1½-liter Mercedes-Benz W165 cars, specially built for the occasion. Their chassis and bodies were like those of the W163, but the two-stage blown engines were chunky little V8s that were a good deal more powerful than the straight-eight Alfetta. They ran away with the race; but the psychological battle had been won even before the race started.

It was not the first time that a special Mercedes-Benz V engine had been built for a single purpose. In 1937 a 5.7-liter·V12 was created simply for going very fast in a streamlined car that was demonstrated in the Avusrennen with a chassis generically similar to the W125. In 1938 this car was rebodied and taken to the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn, and was driven along it by Caracciola at a speed .of 268.9 mph, the highest ever reached on a public highway.

Daimler-Benz Cease To Exist

The war inevitably put a stop to a lot of things. While it lasted, Daimler-Benz continued the outstanding work they had begun on aero-engines during the 1930s. When it was over, they found themselves with three-quarters of their plant destroyed, communications non-existent, disruption and devastation complete. In 1945, according to a statement from the directors, 'Daimler-Benz had ceased to exist'. A new start had to be made. People and equipment were gradually brought together again, and the company could begin on a provisional programme in which vehicle-repair work was predominant.

The date from which things began to improve rapidly was 21 June 1948: the effect of the currency reform then introduced was nothing less than startling, and the firm was suddenly freed from its paralysis. It meant hard work, but that seemed natural enough, and within a year new cars were again being built. For a while they had to be old models, the 170V being the obvious choice; but during 1949 a new model appeared, the 170S. Its engine, though still a side-valved four, gave 52 bhp instead of 38, and the improved performance was well within the capabilities of the newly refined chassis which gave the car roadholding and braking that was outstanding by contemporary standards.

One intriguing feature of the all-independent suspension was that the front wheels were given a measure of longitudinal freedom or 'compliance' (years before the adoption of radial-ply tyres, which forced other manufacturers to do likewise) by pivoting the entire wishbone assembly around a vertical chassis pin. In fact the arrangement could be traced back to the suspension of the 750 kg racing cars, and the idea went back even further to the kick-shackles of the big blown sixes built in the 1920s.

The Mercedes-Benz 170D

The little diesels had not been forgotten either. Launched at the same time as the 170S was the 170D, which gave 170V speed with even greater economy and economy was very much the watchword in the late 1940S and early 1950s. Not until 1952 did the diesel get the same smart body as the 170S, and by that time it was already well on its way to endearing itself to the world's taxi drivers, who have remained faithful to the principle and to the make ever since. By then it was clear that not everybody was hard up, and the old tradition of topping off the range with a de luxe model was revived.

The 220 of 1951 was virtually a 170S with a six-cylinder engine of modern short-stroke proportions coupled to a gearbox with synchromesh on all four speeds. It was this car that established the entire post-war generation of Mercedes-Benz as cars of fine quality, outstanding strength and durability, and performance and roadholding well in excess of anything that seemed reasonable. The 220 and its successors remained without a real equal -but there was a superior, when MB released the big six-seater 300 in 1951, whose sophistication was augmented by an overhead camshaft and new combustion chamber of wedge shape for its 125 bhp engine, and by auxiliary torsion bars brought into action by an electric switch for increasing the rear suspension rate when carrying heavy loads.

The real promise of Mercedes-Benz chassis and suspension design began to show signs of fulfilment in 1953. That was the year when the elegant oval-tube cruciform chassis frame was replaced in the big-volume models by a pressed-steel platform chassis with the engine and front suspension mounted on a subframe. More important and progressive was the rear suspension, in which the geometric shortcomings of the old-established swinging half-axle were successfully corrected without losing any of the spatial and comfortable virtues of the system. The single-pivot rear axle, in which the entire final-drive casing was made integral, with one half of the axle, allowed the rear roll centre to be lowered by several inches; and the old trunnion pivots had their longitudinal wheel location duties taken over by simpletradius arms trailing from a convenient corner of the chassis platform and actually taking the spring loads.

The Brilliant Mercedes-Benz 300SL

Mercedes-Benz were getting cleverer than ever. The following year saw production of the outstanding 300SL. Its practical proof had been in the sports-car races of 1952 - such as the 24-hour Le Mans race, the Carrera Panamericana, and the sports-car Grands Prix of Switzerland and Germany, all of which it won. Everyone raved about its streamlined two-seater body with gull-wing doors, and about the prodigious power and extraordinary flexibility given the inclined 300 engine by direct fuel injection into the cylinders. The speed of the car shook the Jaguar team when they met in the Mille Miglia; but there was even more than that to the 300SL.

It had the first true space-frame chassis, a properly triangulated structure of small-diameter steel tubes subjected only to axial loads and giving the car a foundation of exceptional lightness and rigidity. 1954 was a good year for marketing the 300SL. It was the year in which Mercedes-Benz returned to the top of the motor-racing tree where it had been undisputed champion fifteen years earlier. The effect was as shattering as it had been in 1934, and engineer Uhlenhaut excelled himself in the development of a new car for the new GP formula, embodying all that experience had shown valuable and more that advanced technology showed desirable.

The Invincible W196

It could be argued today there there was never a first-class racing car that had so many innovations over previous iterations as the 2½-liter unsupercharged W196 Mercedes-Benz, nor ever such a car so successful. Defeated only twice in 1954 and only once in 1955, it dominated GP racing in both seasons, sometimes as a dramatic streamliner with all-enclosed bodywork, sometimes as a matter-of-fact bare-wheeler. It had a space-frame chassis, all-independent suspension (of a new low-pivot design at the rear), enormous inboard brakes, complex fuel and electrical services, adjustable-rate rear springing to cater for diminishing fuel loads during a long race, and a built-in aura of well engineered invincibility.

The traditions of the de-Dion axle, which Mercedes-Benz had established, were broken by Mercedes-Benz; their traditions of welded fabrication for the engine cylinders were sustained, and likewise the elegant old straight-eight configuration. Yet it was a brilliantly innovative engine, having not only direct fuel injection but also springless desmodromic valve actuation. It had a sports-racing counterpart in the two-seater W196/110 (better known as the 300SLR) which had a 3-liter engine with a cast cylinder block instead of welded steel forgings, and which won (inter alia) the Mille Miglia in 1955.

Successful though the W196 was, it was apparently not as fast as it should have been. The explanation of this is that the car had originally been planned to enjoy a longer competitive life than it was eventually allowed, being designed with a view to progressive development over a span of four years. During this time it was intended to raise the power output from the original 256 of early 1954 (282 late in 1955) to 400 bhp, with the aid of automatically variable-length inlet tracts (proved experimentally on the 300SLR), to supply that power through all four wheels (there was a differential between the front brakes on the first 1954 cars), to check it with air brakes, and generally to be very clever indeed.

Levegh crashed a 300SLR at Le Mans in 1955 with horrifying consequences, and Daimler-Benz got out of racing as soon as it could. The firm carried on, though. In 1958 they introduced fuel injection (not direct, as in the racers and the 300SL, but into the ports) to the world of the big comfy family saloon, making it a big, comfortable and jolly lively saloon in the form of the 220SE. In 1959 they bought the controlling stock of Auto Union and thus took the DKW and Audi ranges under their wing for a few years, during which they were responsible for the engine design and much more in the progressively improved Audi range culminating in the

Audi 100.

In 1961 they had a Jubilee to celebrate: they opened their now famous museum, they won the Safari Rally, and brought out the 220SE coupe and the air-sprung 300SE, completing a new range of bodies with the 190 and 190D - and although Germany was now prosperous, Daimler-Benz did not forget their flourishing export markets, their occasionally economically-minded customers, nor the world's taxi-drivers. They did not forget their Grosser tradition either: in 1964 they produced the

600, an enormous luxury limousine driven by a 6.3-liter V8 engine.

The progressive easing of fiscal constraints that had made large engines unpopular in Europe encouraged Mercedes-Benz to make bigger and more powerful cars throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, either by enlarging the small in-line six to 2.8 liters, or by designing a new 3.5-liter V8, or simply by shoehorning the 6.3-liter V8 into the 300 chassis. As social and legislative pressures built up to raise the standards of motoring safety, the company's engineers stayed well ahead of the game by concentrating furiously not only on the mandatory secondary safety measures such as crash-survival provisions, but also on primary safety so as to ensure stable and predictable behaviour in emergency manoeuvres.

At the same time they catered for what their customers might appreciate more, with first-class automatic transmissions and power steering, high standards of bodily finish and furniture, and strictly maintained service networks for cars that were now far too complex for the uninitiated to work on with anything other than a cheque book. The culmination of all this was to be seen in 1977 with the four-year-old S series in all its various forms. What appeared at first to be a mere restyling job had gradually emerged as a cogent attack on all the objections that could have been raised against earlier cars made by Mercedes-Benz or indeed by anybody else.

When the trailing-arm rear suspension was modified by the superimposition of a Watt linkage calculated to resist pitch changes in acceleration (and to a lesser extent in braking), to suit the greater power of the 4.5, 5.0 and 6.9-liter V8s, then the 450SE, SL, SEL the supremely elegant SLC cars and the smaller W123 200 series cars became not only the pride of Mercedes-Benz but also the objects of greater critical acclaim. Of course the company continued to go from strength to strength, and remains one of the very few that can make the claim that they make the best cars in the world.

Also see: Mercedes SL - A Sporting Heritage (AUS Site) |

Mercedes History |

Mercedes SL's By Model