|

Lotus

|

1952

- present |

Country: |

|

|

The Lotus 3

It could be argued that the car that made Lotus, and Colin Chapman, was the "3". Built in 1951 for 750 Formula racing, it complied with the regulations for club events (based on old and prolific Austin 75) but it was so scientifically different from the amateurish hacks with which it competed, so tiny and light and fast and stable, that the amazement that greeted its early performances was soon replaced by a resentful and unmerited jealousy.

Where his rivals used hacksaws and blow torches, Chapman used his brain; and with the assistance of his North London friends, Michael and Nigel AlIen, he built a car that exploited every loophole in the regulations, corrected every problem in the basic Austin's design and demonstrated most of the ways in which a trained engineer was better than a gifted mechanic.

The Austin parts that had to be used - the frame, the engine, gearbox and rear axle were heavily modified, while the rest of the car - the split-axle independent front suspension, the hydraulic dampers and brakes, the tubular superstructure that stiffened the chassis, and the 68lb aluminum two-seater body, demonstrated Chapman's critical awareness of what was necessary to make the car competitive.

The success of the car in a season of circuit racing proved how right his approach was: the Lotus was so much faster than its rivals that the difference was absurd, yet despite the apparent fragility of all its little weight-shorn components it was very reliable. There were people wanting Chapman to build them replicas, others wanting him to produce developed versions of the trials cars which first bore the name Lotus - the modified Austin 7 Lotus Mk1, and subesquent Mk2 which had evolved courtesy of a Ford engine.

Chapman established the Lotus Engineering Company on January 1st, 1952. He was only a spare-time proprietor, working during the day as a structural designer for the British aluminum Company, where his talents and engineering degree had taken him after his National Service in the Royal Air Force. In the evening, and for half the night, Chapman laboured on the cars, the fort being held during the day by his partner, Michael Allen.

The Hornsey Stable

Part of an old stable in Hornsey was converted into a workshop, where a few examples of Mk 3 and 4 were successfully built. Chapman's business model was in the development of a sports car that customers could complete themselves from kits that he would supply, installing their own choice of engine and gearbox. Such a car would be eligible for a wider range of competitions than the Austin 750, and there were sufficient suitable parts available from Ford spares lists to permit rationalisation of the purchase of all those parts that Lotus were not in a position to make themselves.

Thus the Lotus 6 was born, based upon a multi tubular chassis' that was a nearly complete space frame, most of the missing diagonals being replaced by stressed body panels (the floor for example) riveted to the tubes of the framework. Complete with its body panels and all the brackets necessary for mounting the engine, the transmission, the live rear axle and the divided-beam front suspension, the chassis weighed only 120 lb. With a Ford or MG engine of up to 1½ liters installed, the Lotus 6 was notable for exceptional acceleration from low speeds and very good roadholding. Its effect on the British competition scene was amazing - but for Lotus is was not all smooth sailing.

There was a critical period in 1953 when the firm almost sank, when Allen was obliged to withdraw, the two full-time mechanics had to be dismissed, and the company was reformed into a limited company. Obsessed as ever, Chapman carried on working. The Lotus 6 however was such a success that it managed to put the little company on its feet again. By 1955, 100 examples had been built, and the little square-cut lightweight had built itself an enviable reputation on the racing circuits and hill-climbs of Britain.

Frank Costin and the Lotus 8

Long before it went out of production, however, Chapman was irritated by it. He was very much the perfectionist, painfully aware of any design's shortcomings, and always anxious to do better next time. Enter

Frank Costin, brother of the Mike, who had for some time been helping Chapman when not gainfully employed with the De Havilland Aircraft Company. Frank was with De Havilland too, working as both a theoretical and a practical aerodynamicist, but before long he was fired by the same enthusiasm as had driven many others into willing slaves for Lotus. He applied himself to the design of what was to become the Lotus 8, concentrating on low drag and directional stability - the latter demanding the long tail fins which were a feature of his design, and which served to keep the aerodynamic centre of pressure well to the rear.

The low drag was achieved by means that were equally straightforward to the aerodynamicist, and foreign to the motor industry, and the result was a body that was at once beautiful, distinguished, and effective. Frank Costin and Colin Chapman were both carried away by the structural possibilities inherent in the all enveloping body shell, and allowed themselves to be persuaded that if the body were partially stressed it would make a useful contribution to the stiffness of the car's structure as a whole. The chassis was essentially similar to that of the Lotus 6 (the most important differences being a de Dion rear axle and a 1½ liter MG engine), but the semi-integral body of the prototype Mk 8 proved too difficult to effect repairs or when any major work was needed on the engine or transmission.

Colin Chapman with future wife Hazel in their first car to wear the Lotus name, the Mk 1, based on an Austin 7 chassis.

Colin Chapman with future wife Hazel in their first car to wear the Lotus name, the Mk 1, based on an Austin 7 chassis.

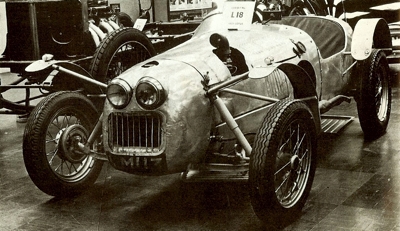

1951 Lotus 3, the first of Chapman's wind-cheating designs.

1951 Lotus 3, the first of Chapman's wind-cheating designs.

1958 Lotus 7, which switched to production by agent Caterham car sales in 1975.

1958 Lotus 7, which switched to production by agent Caterham car sales in 1975.

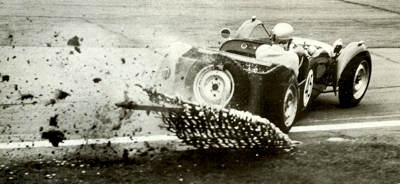

BMC Engined Lotus 7 driven by A. D. Kilburn at Goodwood in 1961.

BMC Engined Lotus 7 driven by A. D. Kilburn at Goodwood in 1961.

1965 Lotus Mark 9, the first Lotus to emerge from the factory after Chapman secured the services of Frank Costin.

1965 Lotus Mark 9, the first Lotus to emerge from the factory after Chapman secured the services of Frank Costin.

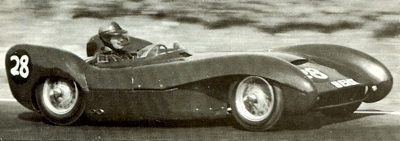

Lotus 11 photographed at Monza in 1956, and this could quite possibly be the car that achieved a staggering lap speed of 143 miles per hour.

Lotus 11 photographed at Monza in 1956, and this could quite possibly be the car that achieved a staggering lap speed of 143 miles per hour.

Graham Hill behind the wheel of a Lotus Mk 12 single seater, first used in Formula Two in 1957.

Graham Hill behind the wheel of a Lotus Mk 12 single seater, first used in Formula Two in 1957.

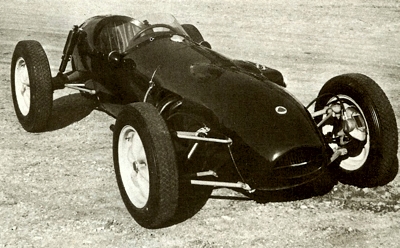

Lotus 12 in profile. It raced in 1957, 1958 and was converted for use in the Formula One class, with Coventry Climax 2 or 2.2 liter power.

Lotus 12 in profile. It raced in 1957, 1958 and was converted for use in the Formula One class, with Coventry Climax 2 or 2.2 liter power.

Lotus launched into the road GT market with the beautiful Mk 14, the Elite, of 1957.

Lotus launched into the road GT market with the beautiful Mk 14, the Elite, of 1957.

The Lotus 16 was announced in 1958 to supersede the 12 in Formula One and Two.

The Lotus 16 was announced in 1958 to supersede the 12 in Formula One and Two.

1959 Team Lotus 16.

1959 Team Lotus 16.

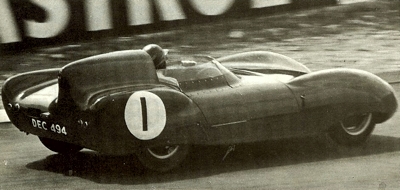

The Lotus 18 was the first rear-engined Lotus, and it would give Lotus their first GP win in 1960.

The Lotus 18 was the first rear-engined Lotus, and it would give Lotus their first GP win in 1960.

Lotus 18, which was originally built as a Formula Junior car, but was subsequently updated to Formula One and Formula Two specifications.

Lotus 18, which was originally built as a Formula Junior car, but was subsequently updated to Formula One and Formula Two specifications.

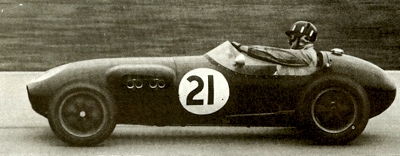

In 1961, the Lotus 18 was replaced in F1 by the 21, still with tubular chassis and 1500cc Coventry Climax engine.

In 1961, the Lotus 18 was replaced in F1 by the 21, still with tubular chassis and 1500cc Coventry Climax engine.

Jim Clark driving the first Lotus Grand Prix car to be endowed with a monocoque chassis, the Mk 25. It would give Clark his first F1 championship, and it formed the basis for all future F1 car design.

Jim Clark driving the first Lotus Grand Prix car to be endowed with a monocoque chassis, the Mk 25. It would give Clark his first F1 championship, and it formed the basis for all future F1 car design.

The Lotus 30 was one of the few failures to come from Lotus. Built in 1964, it used a backbone chassis and 4.7 liter Ford V8.

The Lotus 30 was one of the few failures to come from Lotus. Built in 1964, it used a backbone chassis and 4.7 liter Ford V8.

The first Lotus Elite was a great little car, but plagued with problems. It was very expensive to build, and eventually the glassfibre body was replaced by a backbone chassis and the Coventry Climax engine gave way to the Lotus-Ford twin-cam, creating the Lotus Elan. Pictured above is a Series Two version, which replaced the original 1962 model in 1965.

The first Lotus Elite was a great little car, but plagued with problems. It was very expensive to build, and eventually the glassfibre body was replaced by a backbone chassis and the Coventry Climax engine gave way to the Lotus-Ford twin-cam, creating the Lotus Elan. Pictured above is a Series Two version, which replaced the original 1962 model in 1965.

Lotus Mk 33 Grand Prix car, which had heavily modified suspension over the 25, along with wider tires. Jim Clark would get his second World Championship in the 33 in 1965.

Lotus Mk 33 Grand Prix car, which had heavily modified suspension over the 25, along with wider tires. Jim Clark would get his second World Championship in the 33 in 1965.

The Lotus 49 first appeared in the Dutch Grand Prix in 1967. The chassis was based on the BRM H16, but it used a brand new Cosworth-Ford V8. Jim Clark would win the Dutch Grand Prix.

The Lotus 49 first appeared in the Dutch Grand Prix in 1967. The chassis was based on the BRM H16, but it used a brand new Cosworth-Ford V8. Jim Clark would win the Dutch Grand Prix.

1968 Lotus gas-turbine powered car was revolutionary for the Indy, not only in power, but also in shape. The custom body led the way for the Formula Three 61 and Formula One 72. It was a beast, and claimed the life of driver Mike Spence.

1968 Lotus gas-turbine powered car was revolutionary for the Indy, not only in power, but also in shape. The custom body led the way for the Formula Three 61 and Formula One 72. It was a beast, and claimed the life of driver Mike Spence.

The Lotus 56B was used in several Formula One races in 1971, and was based on the earlier 56 built for Indianapolis. It was powered by a Pratt and Whitney gas-turbine driving all four wheels.

The Lotus 56B was used in several Formula One races in 1971, and was based on the earlier 56 built for Indianapolis. It was powered by a Pratt and Whitney gas-turbine driving all four wheels.

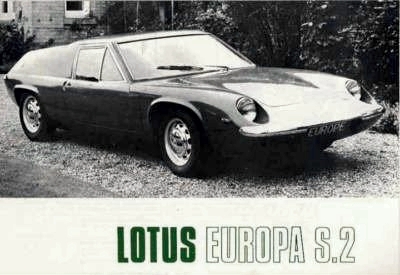

1969 Lotus Europa S2.

1969 Lotus Europa S2.

1969 Lotus Europa S2.

1969 Lotus Europa S2.

1970 Lotus Mk 63, which featured four-wheel-drive. To do this, the engine was mounted backwards.

1970 Lotus Mk 63, which featured four-wheel-drive. To do this, the engine was mounted backwards.

By 1971 the Lotus Elan was in its 5th series, with the announcement of the Sprint. This version featured a new big-valve twin-cam engine developing 125 bhp.

By 1971 the Lotus Elan was in its 5th series, with the announcement of the Sprint. This version featured a new big-valve twin-cam engine developing 125 bhp.

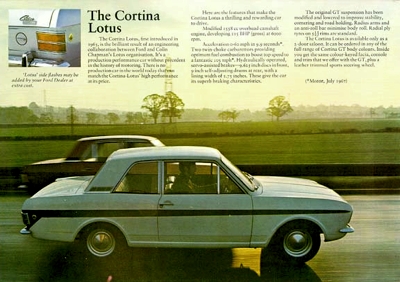

The Lotus-Cortina signalled a great marriage between the two companies.

The Lotus-Cortina signalled a great marriage between the two companies.

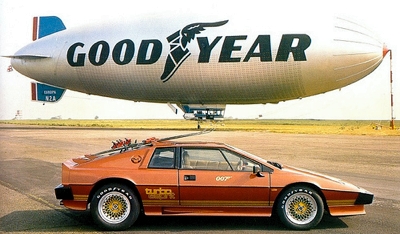

Along with the classic Aston Martin DB5 that starred in the 1964 film Goldfinger with Sean Connery as the fictional Mi6 agent, the Lotus Esprit driven by Roger Moore in the 1977 "The Spy Who Loved Me" is one of the most recognizable 007 cars of all time.

Along with the classic Aston Martin DB5 that starred in the 1964 film Goldfinger with Sean Connery as the fictional Mi6 agent, the Lotus Esprit driven by Roger Moore in the 1977 "The Spy Who Loved Me" is one of the most recognizable 007 cars of all time.

Lotus Esprit Turbo.

Lotus Esprit Turbo. |

Team Lotus

Despite these problems, the Lotus 8 was extremely successful in competition during the 1954 season. It was not allowed to interfere with production of the component-form Mk 6, as Chapman had already decreed that the two activities were to be separated. Production of the 6 was a strictly professional undertaking by the company, the work being done by a full-time paid mechanic. For development of the prototype Mk 8, Chapman formed Team Lotus, staffed by unpaid volunteers, while he and Mike Costin continued to burn the candle at both ends. Things were getting busier and busier: on the one hand Chapman was already working on the Lotus 9, which was to be a direct successor to the 8, while at the same time the 8 had to be modified to meet the requirements of a number of customers who demanded that theirs be powered by the 2-Iitre Bristol engine, in which form it became known as the Mk 10.

Strapped to the Hood

With considerably more power and rather more weight under the bonnet than ever before, the Lotus 10 needed some structural revision, and a redistribution of masses; furthermore the height of the Bristol engine imposed a necessity for a rather unsightly bulge in the bonnet. By the beginning of 1955 it was obvious that business would continue to grow, and Chapman and Mike Costin began full-time work for Lotus. In the Spring of the year the Mk 9 made its appearance, cleaner and simpler, shorter and lighter than the 8, and a little stronger and somewhat easier to work on. Costin had revised the body shape with all these things in mind, and also with the benefit of knowledge he acquired during development work on the 8 - work which included being strapped to the hood so that he could study the behaviour of airflow under the front wheel arches at speeds of up to 110 mph.

What made the 9 particularly attractive was the new Coventry Climax 1100 cc overhead-camshaft engine, one that had been developed from a lightweight fire-pump design, and was just beginning to make its considerable impact on motor sport. The Lotus 9 was eventually offered in two versions, the Club and the Le Mans: the former had a modified Ford 10 rear axle, the latter a proper de Dion assembly and enormous steel-lined Elektron brake drums. The Le Mans car, being intended for serious international competition, had the Coventry Climax engine as a matter of course, with an MG gearbox; the Club Mk 9 could have either that or a modified Ford 10 engine and gearbox. Each was a very effective car in its proper environment, but obviously it was the more expensive one that attracted most of the attention. Indeed it was the first Lotus to which a full retail price could be attached, as customers were now buying complete cars as an alternative to buying a kit of parts and completing the assembly themselves in order to avoid purchase tax.

1955 was a lively season for Lotus drivers in competition, including Chapman himself in an MG-engined Mk 9 built to keep the Lotus competitive in the 1½ liter class. It was also a busy time for development, with particular work being put into the disc brakes that were soon to replace the troublesome Elektron drums. By the end of the year things were busier still, as Lotus had made their first appearance on the floor of the London Motor Show, attracting tremendous interest. The cars had after all gone very well in major and minor British races, and made an impressive foray to the 24 hours sports-car race at Le Mans - though not without mechanical troubles, and not with any eventual success, the car being disqualified, when Chapman reversed back on to the road after a brief departure from it, while running perfectly and being well placed in its class and on the index of performance.

The Lotus 11

The Lotus show stand featured the Lotus 9, but as soon as the Show was over, work began at Hornsey on the prototype 11, which was to be the only basic model to be produced. Three variants would meet the requirements of a greater number of potential customers than ever before: the Le Mans model with 1.1 or 1.5-liter Coventry Climax engine, de Dion axle, disc brakes (inboard at the rear) and a choice of final drive ratios, as the pride of the line; second the Club model, with a live rear axle, drum brakes and a smaller Climax engine; third and catering for a new class of customers was the sports model, an essentially cheap and light car intended for economical road use and perhaps a little mild competition, which it was suprisingly effective at despite having only a side-valve Ford 1172 cc engine.

Frank Costin really excelled himself with the body of the 11, which for serious high-speed work could be fitted with a fairing behind the driver's head and mating with the low wrap-around windscreen. This arrangement not only reduced drag but also helped maintain directional stability, and Costin did some very interesting development work on the shape of the fairing: its size was adjusted until attached flow was just maintained. Some indication of the efficiency of Costin's design was given later when an 1100 cc Lotus 11 took a number of records at Monza. Aerodynamically different from the standard cars only in having a complete perspex bubble canopy over the driver's head in place of the open-topped windscreen, this car put in a lap at 143 mph and an hour at 137.5. It was an immensely effective car, and attracted some of the most notable drivers of the day - and Le Mans was kinder too, Lotus netting a win in their class and fourth in the index of performance.

The Lotus 12

Such was the impetus of the Lotus competition career that Chapman was encouraged to embark on his first pure racing car, a Formula Two single-seater, for 1957. This was the Lotus 12, a car that has never really emerged from the obscurity that its mediocre success earned it, but which is of absorbing interest as the first embodiment of a number of design principles that Chapman was later to incorporate in other more successful models. In essentials the Lotus 12 was a car designed primarily for light weight and low drag so as to be able to exploit to better purpose the power of the Coventry Climax engine that would also be used in rival cars. To this end it had a space-frame chassis and a very closely fitting body, within which the driving position was lowered as much as possible (despite the central transmission line) by the use of a special all-indirect gearbox, built integral with the final drive housing.

This gearbox, designed for Lotus by Richard Ansdale and Harry Mundy, was a conceptually brilliant five-speeder offering everything that a racing gearbox should have - lightness, high transmissive efficiency, easy alteration of ratios, and the essential step-down facility that enabled the prop shaft to be lowered - everything except reliability. By the time the reason for persistent failures was discovered (under power, the gears flung most of the oil away from themselves, and thus committed suicide) it was too late. Two other features of the car were however successfully proven and were to remain in use for many years.

One was the magnesium disc wheel, based on the principle of the convoluted or wobbly web: in this, the architectural notion of a sine-wave wall (which is notably stiff in relation to its mass) is translated into metal, the disc portion of the wheel being in effect a crimped quasi-cylinder so that its undulations are steeper near the hub than they are near the rim. The effect was to dispose a minimal amount of material to give a strength proportional to the loads to which it will be subjected always the focal object of Chapman's chassis design - while susceptibility to fatigue failure was reduced by the absence of apertures such as exist between the spokes of more conventional light-alloy wheels.

The Chapman Strut

The other enduring feature of the Lotus 12 was its independent rear suspension, the first example of what became known as the 'Chapman strut'. The object here was to contrive a geometry of rear-wheel movement similar to what had already been arranged at the front of previous Lotus models, with their split axles and low pivot points giving a favourable change of camber under the influence of cornering induced roll.

Structurally, the Chapman strut was analogous to the MacPherson strut system of independent front suspension, the distinguishing feature being Chapman's very clever use of the universally jointed drive shafts as elements of the suspension. What followed next was inevitable on at least four counts. The wide separation of the load paths from the Chapman strut rear suspension made the system suited to a stressed skin body, and it was inevitable that he should be tempted to try it. In any case, his obsession with the creation of automobile structures having the greatest possible stiffness while employing the least possible mass of material made it inevitable that sooner or later his elegant tubular space frames would give way to a more efficient stressed skin or even monocoque hull.

The ambitions of the young company were such that they were sure to be seduced by the idea of a high-quality closed car that would be fun to drive on the road, while having all the characteristics of a racing car, so as to earn Lotus respect among motoring connoisseurs that had already been won among motor-racing enthusiasts. Finally, and with equal inevitability because it was a young and still inexperienced company, it would never make that car as good as it could have been, simply because unrealistic pricing made its constructors unable to do the job as properly as it should have been done.

The Lotus 14 Elite

In the Lotus 14 all these things came to pass; breathtaking in its beauty, heartbreaking in its fallibility, perfect in conception, but very wrong in its execution. The Lotus Elite was an aesthetic triumph and a commercial disaster. Much of the machinery of the Elite came from the Formula Two Lotus 12, notably the Chapman strut rear suspension, the double-wishbone front suspension, the disc brakes, and (in a new more mildly tuned 1216 cc version) the Coventry Climax engine.

The unitary body in which these elements were housed was wholly new, completely revolutionary, and an extremely courageous venture. Chapman had for some time been intrigued by developments in the technology of glass reinforced plastics, and eventually decided that GRP would be the material of his new car. Careful stress analyses were necessary so that the thickness of the panels could be proportioned to the loads they were carrying, actual figures varying from 0.06 to 0.2 in, and at a later stage to as much as 0.38 around the final-drive mounting.

As is usual in structures of this type, the Elite was composed of a series of boxes but the formation of these was contrived in an unusual way by moulding the car in three major sections which were assembled vertically to produce an immensely stiff bonded sandwich. The lowest layer was a full floor, complete with wheel arches; the uppermost was the curvaceous body that had been given elegant styling by Peter Kirwan-Taylor and aerodynamic efficiency by Frank Costin; between was another layer composed largely of diaphragms imparting vertical, diagonal, and further torsional stiffness to the assembly.

All these, and therefore almost the whole car, were composed of resin-bonded glass fibre; there were only two areas in which metal inclusions were made to accept locally high loads and distribute them more generally into the GRP hull. One of these was in the diaphragm area surrounding the radiator intake tunnel, where engine and front suspension loads were concentrated; the other was a tubular hoop surrounding the windscreen and extending vertically downwards to support the door hinges and finally to emerge beneath the bottom of the car and serve as jacking points.

It was late in 1956 that work was started on the Elite, and a year before it made its bow before the public at the London Motor Show. Another year of painful development - much of it in the hands of carefully selected racing customers - was necessary before it was fit to sell to the public; and only in the evolved forms produced in the last couple of years of its production, which formally ended in 1961 with 998 examples built, did it justify its early promise and emerge as a well integrated and convincing expression of all that could be considered beauty in a car, whether static or dynamic.

The Bristol Aeroplane Company

Many alterations were made, the most urgent being a triangulation of the rear suspension radius arm to check the distortion that allowed the driving wheels to do too much of the steering. Almost equally important, in view of the unsatisfactory quality of the early body shells, was the transfer of their manufacture to the Bristol Aeroplane Company. The Elite was campaigned in every imaginable kind of race, faring exceptionally well at the

Nurburgring and at Le Mans.

High-performance versions produced late in its career included the Special Equipment model, with a delicious ZF gearbox replacing the cheap and nasty MG version of the standard specification, and ultimately the Super 95, which enjoyed that number of horsepower and a more complete and lavish detail specification than any other production Elite. In retrospect there was very little wrong with the Elite, and hardly any of that was the fault of the car itself. It is true that there was an unfortunate resonance at about 4000 rpm, which made the interior somewhat uncomfortable, but in town the revs tended to stay below that figure, and in the country above it, while for some reason the substitution of a diaphragm spring clutch was found - albeit too late to matter - to cure the malady.

What really handicapped this conceptually superb car were commercial mistakes. It should have been priced higher and commensurate quality control exercised; instead it was bodged in detail and the company lost money on everyone. Perhaps the greatest mistake of all was offering it in kit form, especially when you consider that at the time, Lotus were seekng a reputation for excellence. Critics believed that many of the ideas that had been employed when the company was started a few years earlier were now outmoded.

The Lotus 17, a successor to the 11 for small-capacity engines, with strut suspension and general design by Leonard Terry, was not particularly convincing; the move to new factory premises at Cheshunt in Hertfordshire was. When, a few months after this took place, a new rear-engined Grand Prix car, the Lotus 18, briefly led the Argentine Grand Prix in February 1960, it was clear that while credit must be given to the Coopers for showing what to do in building a Grand Prix car, it was likely to be Lotus who would define how to do it.

The Lotus 18

In the Lotus 18, and especially in its suspension, Chapman made advances as important in their context as those in the body of the Elite. The 18 can best be judged by the contrast it afforded to the 16 that raced in the Grands Prix of the previous season. That car had been an abysmal failure; the principles guiding its design were that it should be superior in acceleration through being light, should be faster through corners by virtue of superior roadholding, and should be capable of attaining very high speeds by virtue of minimal aerodynamic drag.

The first and the last of these were achieved, but the roadholding was as unsatisfactory as the car was unreliable. Starting afresh, Chapman sought to espouse a new ideal, to make a car that would exploit every bit of rubber that it could put on the road. All this was achieved in a car that looked superficially crude, but which was in fact a masterpiece of mechanical simplicity and geometrical refinement. From the front-engined type 16 it inherited nothing but the convoluted web-wheels and the Coventry Climax engine which, although producing only 239 bhp, weighed only 290 lb and offered an uncommonly wide spread of useful torque.

The engine was installed behind the driver in a chassis of multi-tubular construction, freely triangulated as to be almost a pure space-frame. Behind the engine was the final-drive casing, and behind that the gearbox; ahead of the half-supine driver's feet, themselves almost in line with the front wheel hubs, the fuel tank was preceded by a three-piece radiator for water and oil. The result was a simple slab-sided box of a car, of which no part other than the windscreen stood higher than 28 inches.

By reducing frontal area, Chapman regained what ultimate speed might have been lost by want of aerodynamic refinement. He also kept the car light, it scaled when empty only 980lb, almost exactly the same as the type 16 - and to the surprise of everyone else, the removal of the engine from the nose of the car to the tail paradoxically resulted in the front wheels of the new car carrying four per cent more of its weight than did those of its predecessor.

To suit his scheme for a supremely roadworthy and responsive car, Chapman devised a new suspension system. At the front it was ordinary enough, with pairs of unequal-length wishbones that placed the instantaneous roll centre fairly close to ground level. The surprise was at the rear, where the roll centre was brought down to a similar altitude. As in the type 16, the axially rigid but universally jointed half shafts served as suspension links, so that in a transverse plane each could be considered to act in lieu of a wishbone.

Well below each shaft was a proper wishbone, its apex almost on the centre line of the car beneath the gearbox, its base anchored in the bottom of the cast light-alloy hub carrier; by bringing this casting very near to the ground, the upper and lower links diverged away from the car's centre line. Since they were also of different lengths, this geometry would ensure that, as at the front, the wheels would assume a fairly pronounced negative camber as they moved upwards towards the bump position, so that even if the car rolled outwards due to the centrifugal forces liberated in cornering, the all-important outer wheels would remain substantially perpendicular to the road surface.

With the roll centres and thus the roll axis of the car fixed only an inch or so above the ground, weight transfer from inner to outer wheels during cornering was dramatically reduced. A corollary was that the roll couple would be considerable, so that the car and its wheels would tend to tilt outwards on corners to a degree that might degrade the cornering power of the tyres. Only a little of the weight transfer was restored by the addition of anti-roll torsion bars to the front and rear suspension; but these limited the lateral rotation of the car about its roll axis to only 4°, and the novel use of such a bar at the rear as well as at the front made it possible for the car to retain the balance that Chapman had hoped to achieve.

It only remained to supply some form of longitudinal constraint for the rear suspension, and this was easily done by pairs of parallel radius arms, extending from the top and bottom of the hub carrier. In a very short time the Lotus 18 proved itself the fastest car in the history of Grand Prix racing. In a little longer, it was being avidly copied by all other racing-car constructors. A two-seater sports-racing version was built with full-width bodywork (numbered 19 and known as the Monte Carlo) and this Lotus enjoyed similar emulation.

People were no longer incredulous; they were convinced. For a dozen years to come, practically every constructor of racing cars, successful and unsuccessful alike, sooner or later copied what Lotus had done. Chapman demanded efficiency not only of car, but of the men that drove them, it becoming a byword in automobile engineering. There were times when suspension or steering components would come apart, or wheels would fall off, times when a driver noted for his courage grew very petulant about the relative chances of breaking records or his neck, and times when it all held together so that this beautiful fragile creation might demonstrate that ineffable superiority which declared Chapman to be the most shrewd and perceptive designer in Grand Prix racing.

The Lotus 25

Then came the Lotus 25, the first Grand Prix car to have a stressed-skin hull. Critics insisted that it was a mere double-tube structure, but this was an unfair description of a punt-shaped hull stiffened by two very large longitudinal torsion boxes. The weight of the egg-shell fabrication was 1/16th that of the total machine, but its strength and stiffness were unimpeachable. All the ancillaries were studied with an eye resentful of every ounce, however the habitual delicacy of appearance and occasional fragility of construction which characterised not only the Lotus but also many other cars created in its image.

The Lotus 25, which first appeared at the Dutch GP in 1962 with a Coventry Climax V8 engine of 1½ liters, had a torsional stiffness three times greater than that of the interim space-framed 1961 car, the type 21, while the frame weighed little more than half as much. To give it further superiority, Chapman reduced the frontal area to a mere 8 sq ft by making the driver lean back further than ever, and giving him a steering wheel only a foot in diameter, packing him and his controls and every possible ancillary well down inside the car, allowing as little as possible to protrude outside.

Sure, not all of this was original work - the inboard front-suspension units were hailed at the time as a wonderful innovation, though Maserati had employed them in 1948; the supine driving position echoed the designs of Gustav Baumm for NSU a decade earlier; the revised rear suspension, with upper links relieving the drive shafts of suspension loads, owed something to the inspiration of Eric Broadley and Lola.

The Lotus 33

The Lotus 25 would be continually refined, until it became the Lotus 33, and by 1965 these cars were established as the standard by which all others were judged and most found wanting. The first half of the 1960s, with

Stirling Moss putting up some of the greatest performances of his career in the Lotus 18 and

Jim Clark gradually emerging as the most superlative driver of the time, were great days for Lotus. Successes came thick and fast, not only at world-championship level but also in the lower echelons, where customers for Formula Two and Three single-seaters and lightweight sports-racers were not wanting.

Lotus-Ford Take On The Indy

It was a period in which three important new developments took place. A joint Lotus-Ford onslaught on Indianapolis was one; the others - the

Elan and the

Lotus Cortina - were closely related. The connection was in the engine, which remained famous since its inception in 1962 as the twin-cam Lotus-Ford. In effect it was the new 1½-liter Ford 116E saloon-car engine, surmounted by a special Lotus cylinder head designed for Chapman by Harry Mundy and Richard Ansdale, the same consultants who devised the gearbox for the front-engined single-seat racers. Leaving the low-mounted original camshaft in the block as a jackshaft, they ran a chain to drive two overhead camshafts actuating inclined valves in hemispherical combustion chambers, to which long individual inlet tracts led mixture from a brace of twin-barrelled Weber carburetors.

The Lotus 23

This head was first run experimentally on a 1-liter 105E engine, but its first public appearance was as a 1½-liter unit in the Lotus 23B - and it was an appearance that dramatically illustrated both Lotus ethos and Clark virtuosity. The Lotus 23 was based on a widened version of the Formula Junior Lotus 20, bearing to that space-framed racer the same relationship as did the Monte Carlo 19 to the Grand Prix Lotus 18. With the new engine installed, and the chassis somewhat strengthened, the 23 became the 23B and was entered for the 1000-kilometre sports-car race at the

Nurburgring in 1962. Seventh fastest of all in practice, and easily fastest of the 2-liter class, the little Lotus ran away from the field when the race started in wet conditions, and at the end of the first fourteen-mile lap had a 27-second lead which grew to more than 2 minutes by the end of the eighth. Then the sun came out and the fastest of the opposition (a 4 liter Ferrari) began to close up, while a fractured exhaust pipe made Clark groggy, and eventually put him off the road.

Never Again at Le Mans

While it lasted, this was such a scintillating performance that great enthusiasm attended the entry of two special twin-cam Lotus 23s for Le Mans - a 1-liter car and a 750 cc version. The French scrutineers rejected both these cars out of hand because the front wheels were fixed by four studs and the rears by six, the argument being that the spare wheel could only replace those at one end of the car. Rather than carry two spares, Chapman had the rear hub fixings altered to match those at the front, whereupon the scrutineers said that the cars must now be dangerous and refused to examine them afresh. Chapman was furious, the scrutineers were adamant, and Chapman vowed that team Lotus would never again return to Le Mans. The vow was kept.

The Lotus Elan

Lotus had other ends in view for the twin-cam engine, and the Elan was the first. It was in a sense a replacement for the Elite, albeit cheaper. It was originally an open two-seater, although fixed-head versions were to appear later in its life, and it originally had the 1½-liter engine, although nearly all those produced had a displacement of 1558 cc. By far the most important feature of this car was its chassis, composed of a deep central steel box serving as a torsionally very stiff backbone, forked towards each extremity to accommodate the engine and gearbox at the front and the final drive at the rear. From the ends of the forks the wheels were independently suspended by double wishbones at the front and by a strut and bottom wishbone arrangement at the rear, the drive shafts being simplified and freed from splined slip joints by the use of rubber-centred universal joints.

The Lotus Cortina

Bonded to this chassis and adding slightly to its torsional stiffness was a GRP body, just big enough to enclose the chassis, two adults, and a dog on the bench behind them. The weight of the entire car was less than 1300 lb, and its shape was extremely smooth, aided by headlamps which sank flush with the nasal contours when they were not in use. They were pneumatically raised, and early examples gave endless trouble, due to deficiencies in the vacuum system which allowed the lamps gradually to subside while the car was driven fast. No such excuse could be proffered for the troubles attending the

Lotus Cortina (typed the Lotus 28) which came on the market in the following year. This was based on Ford's newly introduced and very successful

Cortina production sedan, but its performance was greatly augmented by installation of the Lotus-Ford twin-cam engine giving 105 bhp, the utility of that power being ensured by a close-ratio gearbox and a thorough revision of the suspension by Lotus.

The most important of these changes was in the location (almost a re-location) of the rear axle by radius rods and an A-bracket. Tuned versions of the Lotus Cortina were immensely successful on the track, but the rear suspension made the car very harsh on the road and tended to tear the axle apart, so leaf springs made a comeback on the car in 1965, by which time Ford and Lotus were on very good terms. As early as 1963 their collaboration had become close enough to warrant efforts above and beyond the call of Elan and Cortina production duty; Lotus built the Indianapolis type 29, after the fashion of their Grand Prix racers, but on a larger scale to suit the 4.2-liter Ford V8 push-rod engine that Chapman was convinced would be competitive in a car so much lighter, less dragworthy, and more cornerable than the traditional Indianapolis front-engined roadsters.

He was virtually proved right, but in terms of material results the experiment was a failure - albeit less disastrous than the V8 Ford-engined Lotus 30 sports racer of the 1964 season. Later in 1965 Chapman replaced it by a 5.8-liter version, known as the type 40, although American pit crews claimed it was merely a 30 with 10 more mistakes built into it. On the evidence of the car's competition career, they were right. Elsewhere, the Lotus racing programme carried ample evidence to suggest that Lotus rarely made a mistake without learning from it, and seldom made a car that they could not develop into something even better.

The Lotus 34

Out of the beautiful and outstandingly successful Lotus 25 Grand Prix car grew the 33, with revised suspension and steering to accept the wider wheels and tyres that were coming into use in 1964. Structurally related to it, though necessarily larger, was the Lotus 34, built to carry a new four-camshaft racing Ford V8 for Indianapolis. Like the Indianapolis car of 1963, it was faster than any of the opposition, so much so that Lotus cars filled the front two rows of the starting grid. The outcome of the race was even less satisfactory than the previous year, when Clark was in effect robbed of victory by the apparently deliberate refusal of race officials to apply their own rules: the 1964 cars ran on Dunlop tyres that were clearly superior in practice, but which failed during the race, causing Clark's car to crash and the other team car to be withdrawn.

Not until 1965, with a full monocoque Lotus 38, could Lotus win the race, by which time the American teams had accepted the superiority of the British design and were copying it as avidly as other European racing-car constructors were copying the Grand Prix cars from Cheshunt. Adopting the stratagem that has been practised since the days of Henry and the victorious Grand Prix Peugeots, the US Gurney Team lured away Chapman's chassis designer Leonard Terry, who went on to produce Gurney's Eagles. At the time Lotus were in a strong enough position, Clark starting in nine and winning six of the ten Championship Grands Prix of the season, once again becoming World Champion driver, and establishing the Lotus 33 as the most effective and successful car of the year.

Adapting the Indianapolis Mk 38 Design

The future looked less promising, however, as 1966 was to see the introduction of a new formula permitting engines of 3 liters displacement for Grand Prix racing, and Coventry Climax had made it clear that they would no longer be supporting Grand Prix - or indeed any - motor racing any more. By adapting an Indianapolis Mk 38 design, Lotus tried to make the most of the new H16 BRM engine, but that power unit was a disastrous failure, even when eventually it became available late in 1966, and for most of the year the Lotus team had to be content with the old Mk 33 powered by an enlarged Coventry Climax or BRM V8 engine, of the basic type used under the preceding formula. The car was invariably very competitive on the twistier circuits, but not sufficiently reliable.

The Lotus 46 Europa

The only bright spot was the introduction of the Lotus 46, known as the Europa, a sporting two-seater that was very low and featured an aerodynamically refined closed body which shielded an engine and transmission mounted in the racing style behind the driver. Because the car was intended to be cheap and to be marketed initially only in Europe, it was powered by a mildly tuned version of the Renault 16 engine, giving it a performance less than exciting, even if the handling and steering were invigorating. What was most noteworthy about the car, perhaps, was that it was presented at the new modern purpose-built Lotus factory at Hethel near Norwich, where Lotus had at last found room to expand in the manner that Chapman's energies and ambitions had made seemingly inevitable.

Just how strong was not evident until the middle of the 1967 racing season, when a new Grand Prix Lotus, the 49, appeared at

Zandvoort for the Dutch Grand Prix with a Ford-sponsored Cosworth-designed 3-liter V8 engine in the rear of a chassis basically that of the types 42 and 43 built in 1966 for the H16 BRM engine. The Cosworth-Ford, essentially a doubling up of an existing and very successful Formula Two engine, was an immediate success, and Lotus won the race. Thereafter they were faster in every Grand Prix of the season, though they were dogged by unreliability. Not until the following year would Lotus carry off the World Championship again - alas, not with Clark's help, as he was killed in a Formula Two Lotus 48 during a minor German race, and not in the traditional Lotus colours of British racing green with a yellow stripe.

Sponsorship from John Player

Chapman had secured the sponsorship of the John Player tobacco firm, and found by careful reading of the rules that there was nothing to stop him having the cars painted in his sponsor's livery. While teaching the world a thing or two, he continued to learn. The most outstanding new production car of the year was the Lotus 50, better known as the Elan Plus 2 coupe (though the Elan part of the name was later to be eliminated to avoid confusion). This low and wide, and by Lotus standards luxurious, car was in effect an expanded Elan for the family man, with a rear seat that would nominally accept two small passengers, though they would find it sickeningly uncomfortable after very-few miles. The important thing about this car was that it was not to be made available in kit form, despite pleas from customers who were understandably as anxious as ever to avoid having to pay purchase tax on a complete car.

The Plus 2 was a fine machine; for all its faults, most of which were attributable to inadequate quality control, though some of them were due to poor design, it was probably the most roadworthy road car Lotus had yet built, excelling the Elan and Elite in stability and cornering ability, in ride comfort and in quietness, and most of all in its degree of civilisation. Moreover, with a maximum speed of 118 mph and outstanding acceleration up to 60, it would comfortably out-perform rivals of much greater power, as well as competently defeat them in any kind of corner. Something even better was sought in racing, and the promise of four-wheel drive was investigated in an exquisitely elegant design by Maurice Phillipe, who had taken Terry's place as Chapman's right-hand design man in the racing team.

The Lotus Type 56 powered by Pratt & Whitney Gas Turbine

This was the type 56, the novel 1968 Indianapolis wedge, with a Pratt & Whitney gas turbine giving more than 500 horsepower and connected by an ingenious but simple transmission to front and rear wheels. The Type 56 featured four-wheel drive, but that was not enough to keep the vast power of the turbine from making it a real wild child, and Mike Spence was fatally injured in a crash, robbing Lotus of almost certain victory. It was a flop, but it had its aftermath in a new turbine-powered Grand Prix car, and a conventionally engined four-wheel-drive Grand Prix car, that the team's leading driver Rindt would not bother to develop, and that in the hands of others proved distressingly uncompetitive.

Amoung F1 aficionados 1968 is remembered as the year of 'wings', and until they were trimmed by new regulations in 1969, so much experimentation went into the exploitation of aerodynamic down-thrust to increase the cornering power of the tyres without imposing too great a drag penalty that the possibilities of four-wheel drive were shown to be inadequate by comparison. Yet the 56 had its successful aftermath, as well as its two unfortunate legatees, as the wedge-shaped 61 proved effective in the Formula Ford racing in 1969, while the wedge-shaped Lotus 72 which came on the scene in 1970 became a very successful machine.

It did not succeed all at once, like the 49, as the anti-dive and anti-squat effects built into the suspension proved excessive, virtually stopping the suspension from working during acceleration and braking, to the dismay of drivers in general and Rindt in particular. Yet the Lotus 72 rapidly became a classic, and even in its fourth year of competition it was good enough to defeat all competition in race after race. As late as 1974 it was still competitive, which is more than could be said for the Lotus 76 that was supposed to be its successor, with a servo-operated clutch that the driver could control with a button on the gear lever, leaving his feet to work on accelerator and brake pedals only. Chapman's racing cars were the work of an engineer more imaginative, more creative, and more critical of established practice than any of his contemporaries.

The Lotus Elite 75

The 'new' Elite (number 75) was a car for a new class of customer, a car that was a full four-seater, a car that by virtue of clever shaping, ingenious construction, and considerable aerodynamic refinement, it yielded the sort of performance that a Lotus driver expected, while using no more power than a Lotus enthusiast would consider respectable. Its engine was a two-liter four-cylinder, with two overhead camshafts prodding four valves in each combustion chamber, the general design and proportions owing a good deal of inspiration but not much else to the engine of the Vauxhall Victor. It was an engine that earned some money and a little notoriety in the

Jensen-Healey, and established Lotus as engine-builders in their own right.

The Lotus Esprit and Eclat

When launched, the Elite represented only the first stage in the replacement of the entire range. By the end of 1975, the years of the low-cost Lotus sports car had gone, seemingly for ever (Caterham Car Sales had taken over all rights to the Seven and the Elan and Europa variants had been dropped); in October, the Esprit, a new mid-engined two-seater, and the Eclat, a coupe version of the Elite, joined the four-seater in the showrooms. Both cars shared the Elite engine, while the Eclat also used many other Elite parts. Around the same time, Chapman coaxed a Borg-Warner type 35 gearbox into his Elite chassis, thus offering the first ever automatic Lotus.

The Lotus Type 77 JPS II

The 76 having been discarded as a failure, a new Grand Prix car, the type 77 - or JPS II - was announced in late 1975 to take the weight off the shoulders of the ubiquitous 72. Once again, the new car incorporated many innovations, such as fully adjustable track, wheelbase and suspension; however, with so many variables, it was a full season before the 77 achieved its first win, in the hands of

Mario Andretti, at the Japanese Grand Prix. This turned out to be the car's last race, as Chapman again saw fit to launch a new Grand Prix car, the 78- or JPS Mk III - for the 1977 season. This machine's greatest claim to fame was its massive side pods, which not only incorporated the radiators, but were of complex aerofoil section both inside and out.

Victory at Long Beach

Unfortunately, although the down thrust generated by these pods made the car unbeatable through fast corners, it also reduced its top speed, thus making it suitable only for certain circuits. Nevertheless, victory was not long in coming - at Long Beach - and thereafter the car was always near the front. At the end of 1977, Lotus were on top of the world: their racing cars were winning and the road cars were beginning to sell as they should.

The Esprit Turbo, The First Lotus Super Car

Success at the track was turning into success in the showroom, however the Espirit was proving problematic. The S2 and later S3 models went a long way to addressing the problems inherent in the original Esprit, and the next addition to the range, the Lotus Esprit Turbo, took the company straight into the “Super-car” league; the Turbo’s 2.2 liter engine was obviously turbocharged, and was good for 210bhp. Lotus engineers also re-tuned the chassis frame, and there was comprehensive re-style to complement the cars amazing performance. Lotus quoted a top speed of just more than 150mph for the Esprit Turbo, together with the ability to reach 60mph from rest in 5.5 seconds. This sort of performance, linked to the usual matchless road-holding standards and surprisingly frugal fuel consumption, enabled the Esprit Turbo to stand comparison with any other exotic machine.

Ayrton Senna

Chapman passed away in 1982, however even after his death and up until the late 1980s, Lotus continued to be a major player in Formula One. Ayrton Senna drove for the team from 1985 to 1987, winning twice in each year and achieving 17 pole positions. However, by the company's last Formula One race in 1994, the cars were no longer competitive. Lotus won a total of 79 Grand Prix races. During his lifetime Chapman saw Lotus beat Ferrari as the first team to achieve 50 Grand Prix victories, despite Ferrari having won their first nine years sooner. Team Lotus established Classic Team Lotus in 1992, as the Works historic motorsport activity. Classic Team Lotus continues to maintain Lotus F1 cars and run them in the FIA Historic Formula One Championship and it preserves the Team Lotus archive and Works Collection of cars, under the management of Colin Chapman’s son, Clive.

Team Lotus

Team Lotus' participation in Formula One ended at the end of the 1994 season. The Lotus name returned to Formula One for the 2010 season, when a new Malaysian team called Lotus Racing, using the Lotus name on licence from Group Lotus, was awarded an entry. The new team was unrelated to the previous incarnation of Team Lotus when it was first founded, although it was funded by a Malaysian Consortium including Proton (the owner of Lotus Cars). After a dispute between the two parties (Lotus Racing and Proton), Group Lotus, with agreement from their parent company Proton, terminated the licence for future seasons as a result of what it called "flagrant and persistent breaches of the licence by the team". Lotus Racing then announced that they had acquired Team Lotus Ventures Ltd, the company led by David Hunt since 1994, during which Team Lotus had stopped competing in Formula One, and with it full ownership of the rights of the Team Lotus brand and heritage.

The team confirmed that they would be known as Team Lotus from 2011 onwards. In December 2010 Group Lotus (Proton) announced the creation of 'Lotus Renault GP', the successor to the Renault F1 Team that will contest the 2011 FIA Formula One World Championship, having purchased a shareholding in the team. The team's cars will continue to be called 'Renaults', up against the Team Lotus cars which will be known as 'Lotus'.

Formula One Constructors' Championships (Drivers' Championship winner for Lotus)

Also see: Lotus Car Reviews | Lotus History (AUS Edition) | Colin Chapman (AUS Edition)