|

Lancia

|

1906

- present |

Country: |

|

|

VINCENZO LANCIA, born in August 1881, was the son of a well-to-do country Squire who made his money in soup. As a boy, Vincenzo was an adventurer and a dreamer; as a man, he was generous, impulsive and industrious. He was a great patron of the opera, a passionate enthusiast for the music of Wagner and one of the fastest and most furious drivers of his time.

Perhaps all these things were significant in helping us to appreciate the cars which bore his name; or perhaps the only thing that mattered was that some of his formative years were spent in Turin when it was the cradle of the Italian automobile industry.

Welleyes Bicycles

In his teens Lancia was sent to the Turin Technical School, where he was intended to master the trade of book keeping. His family owned a winter residence in the city, and let some premises in the yard to Ceirano, who at that time was engaged in the bicycle trade, producing machines under the trade name of Welleyes.

Eventually, Ceirano produced a small car under the same name. It was the workshop scene that young Lancia had to pass four times each day, and the fascination of the work that went on there, combined with his own romantic notions of an artist among technicians, encouraged him to seek and find there his real vocation.

Ceirano's Apprentice

Somehow he prevailed upon his father to let him work for Ceirano as a book keeper; as soon as he was installed, he set himself to master the craft of the mechanic and the science of the designer - in which latter respect he was assisted by Ceirano's engineer, Faccioli.

Everything that followed seemed to flow from his own innate technical genius, so that Biscaretti was to write: 'The pace with which Lancia mastered the new subject matter, his ability to see technical problems in their proper relationships and his knowledge of motor cars were such that they astonished the few people close to him'. His name became more widely known in the industry of Turin, because he acquired a reputation as a miracle worker for his ability to diagnose and remedy faults in the cars and motor tricycles, which were slowly beginning to appear on the streets.

It was in 1898 that Lancia joined the Ceirano car firm; in 1899, that company was taken over by Fiat. So well known was Lancia's name to Fiat's Giovanni Agnelli, that there was no hesitation in taking Lancia, then only twenty years old, together with the Ceirano workshops and engineer Faccioli. Despite his youth and his brief experience, Lancia was appointed Chief Inspector in the new Fiat factory. It was about this time that motor racing became fashionable.

The tempo of technological development at the time thrust the motor car into the arena of sporting contests, not only as a means of accelerating progress, but also as a very effective medium for advertising. Fiat took enthusiastically to the sport, forming a team from their best drivers: Lancia, Nazzarro, Cagno and Storero. Looking back, it is clear that the greatest of these was Nazzarro, a driver of impeccable precision and great mechanical sympathy.

Lancia was endowed with a less cautious intelligence, but while his cars lasted he was often faster than the rest of the team. His career as a racing driver started in 1900, with a meeting at Padua which he won in a Fiat, and it did not finish until ten years later when he set a speed record with a car of his own design. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of his career is that he was retained by Fiat as one of the most important members of their racing team in the 1907 series of three great races-the Grand Prix of the ACF, the Kaiserpreis and the Targa Florio - which they dominated: a year earlier, Lancia had established his own company.

Vincenzo Lancia, a successful racing driver for Fiat. Long after his death, Fiat would again play a major part in the history of his company.

Vincenzo Lancia, a successful racing driver for Fiat. Long after his death, Fiat would again play a major part in the history of his company.

1908 Lancia 18.24hp, which was later called the Alpha. It is claimed by some historians that the car was capable of 56 mph. Only 108 were built.

1908 Lancia 18.24hp, which was later called the Alpha. It is claimed by some historians that the car was capable of 56 mph. Only 108 were built.

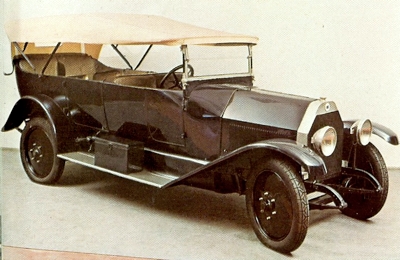

1914 Lancia Theta. 1696 were made between 1913 and 1919.

1914 Lancia Theta. 1696 were made between 1913 and 1919.

1919 Lancia Kappa, derived from the Theta, and powered by a 4940cc 4 cylinder engine developing 35 bhp.

1919 Lancia Kappa, derived from the Theta, and powered by a 4940cc 4 cylinder engine developing 35 bhp.

1927 Series 7 Lancia Lambda, powered by a 2.4 liter engine. It could be purchased as a rolling chassis so the customer could fit their own body-work.

1927 Series 7 Lancia Lambda, powered by a 2.4 liter engine. It could be purchased as a rolling chassis so the customer could fit their own body-work.

Lancia Di Lambda Royal Cabriolet with coachwork by Voll and Rahrbeck.

Lancia Di Lambda Royal Cabriolet with coachwork by Voll and Rahrbeck.

1932 Lancia Artena Limousine, which was fitted with a 1925cc 4 cylinder engine.

1932 Lancia Artena Limousine, which was fitted with a 1925cc 4 cylinder engine.

1934 Lancia Series 2 Augusta Cabriiolet.

1934 Lancia Series 2 Augusta Cabriiolet.

1934 Lancia Augusta Sedan.

1934 Lancia Augusta Sedan.

1936 Pininfarina bodied Lancia Augusta.

1936 Pininfarina bodied Lancia Augusta.

1937 Lancia Aprilia. The cars stressed skin body was pillarless, so that when both doors were open, the was unimpeded access to the passenger compartment.

1937 Lancia Aprilia. The cars stressed skin body was pillarless, so that when both doors were open, the was unimpeded access to the passenger compartment.

1956 Lancia B20 GT.

1956 Lancia B20 GT.

1957 Lancia B24 GT Cabriolet with bodywork by Pininfarina.

1957 Lancia B24 GT Cabriolet with bodywork by Pininfarina.

Lancia Flaminia Coupe with bodywork by Pininfarina.

Lancia Flaminia Coupe with bodywork by Pininfarina.

1971 Lancia 2000 Sedan.

1971 Lancia 2000 Sedan.

Lancia Fulvia Coupe Series 3, with 1300cc engine. Production ceased in 1976.

Lancia Fulvia Coupe Series 3, with 1300cc engine. Production ceased in 1976.

Lancia Flaminia Sport designed by Zagato.

Lancia Flaminia Sport designed by Zagato.

1977 Lancia Beta 2000 Sedan. At launch, the critics claimed it looked to "Japanese".

1977 Lancia Beta 2000 Sedan. At launch, the critics claimed it looked to "Japanese". |

Vincenzo joins with Claudio Fogolin to launch Lancia

It was in November 1906 that the Lancia firm was officially incorporated, the two partners (the other being Claudio Fogolin) having met in the Fiat works, having found that they were compatible in their clear minds, determined wills, and industrious ambition, and having - which can hardly have been less important - 50,000 lire each to put down as initial capital. They rented premises in Turin that had formerly been occupied by Itala, and set to work-Lancia to super- ...... vise the technical side, Fogolin (who had been a test driver for Fiat) to superintend marketing.

It was clear to Lancia from the very beginning that his cars should be unconventional, although it is arguable that at that time no cars could be thought really conventional anyway. Perhaps technical non-conformity is a better description of the Lancia ethos, with no concessions being made. to cheapness or simplicity in manufacture if they involved some debasement of engineering ideals. In his very first design, Lancia put his own ideals into metal; it had shaft drive when chains were commonplace, it was lighter and faster than other models with which it was comparable on the market, and its engine was by the standards of the time very high-revving.

In February 1907 the factory was ravaged and many drawings and parts destroyed by fire. It was a serious blow, but Lancia started afresh and by September of the same year the prototype car was ready for its first test run. Apart from the fact that the door had to be removed from the factory because the car's hubs were so wide that they fouled it, this occasion was a complete success, and a second prototype was promptly built so that development could proceed faster.

The Lancia Alpha

The third chassis was bodied in an elegant double-phaeton style, and in 1908 it was put on the market first as the model 51, later as the 18-24 horsepower and, eventually, as the Alpha. At last the Lancia firm could look forward to some income and, although the car was initially received with scepticism on account of its high engine rating and light weight, 108 examples were built and sold in the ensuing year and a half. The car had a double-block four-cylinder engine of 2½ liters displacement, producing 28 horsepower at 1800 rpm, and was reputed to be capable of 56 mph.

It was quickly to become a success, notably on the English market, and prompted Lancia to acquire new, larger premises. In them, Lancia embarked on a six-cylinder car, the model 53, with a displacement of 3.8 liters. The public did not take so kindly to this machine, despite its impressive performance, and in 1909 Lancia reverted to the in-line four with the 2-Iitre Beta. The tradition of naming cars by steady progress through the Greek alphabet was firmly established, as was the tradition of high-grade workmanship and carefully cultivated technical nonconformity - the Beta had a mono bloc engine construction that was uncommon at the time.

The same design principles led to the Beta being expanded into the 3½-liter Gamma of 1910, the Delta and Didelta (a strengthened version) of 1911, the 4-liter Epsilon and a 5-liter Eta. They did not do at all badly, however, in 1913 came the first Lancia to be a really big success, a car that made its own contribution to progress in the standard embodiment of a complete electrical installation at a time when most cars were given their electrics after construction, on a piecemeal 'customer-option' basis.

The Lancia Theta

Lancia saw that the installation should be integrated with the chassis design, and the 1913 Theta (the mechanical parts of which were developed from a car built for the Italian army) was distinguished by a complete and homogeneous electrical system. The choice of foot operation for the starter, together with a similar control for the exhaust cut-out, endowed this car with five pedals, so that driving it was akin to playing a concert harp on wheels; but 1696 customers testified to the attractiveness of the Theta, and put the Lancia company on what seemed a very promising course, with production increased fifteenfold in the five years since the introduction of the Alpha.

That course was rudely interrupted by World War 1. A V8 engine design, patented only a few days after Italy's joinder of hostilities, had to be shelved, while Iota and Diota chassis served as the bases for trucks, artillery transporters and Ansaldo tanks. Like most-industrial undertakings, the Lancia firm flourished on war work, and like most of them it found itself facing serious problems after the war in keeping the over-expanded factory running, and providing jobs for the workers, while readjusting production to civilian requirements.

It seemed to Lancia that the success of this programme would be conditional upon the building of substantial and modern cars, which could be sold in large numbers. How he reconciled this with the evolution in 1919 of a prototype chassis with a V12 7.8 liter engine and an output of 150 horsepower is not easy to understand; although the engine exhibited in Paris and London enjoyed enthusiastic acclaim, the Italian public was hardly prepared to welcome such a pretentious car, and few were made. Fiscal reasons had a lot to do with it, but it is possible that the more critical customers also entertained some doubts about the narrow included angle of the two banks of cylinders. This was only 20°, when it had already been established theoretically and practically that a V12 should normally be a 60° design, and that the alternatives of 90 and (as in the dreadful American Liberty aero engine) 45° had little to commend them.

The Lancia Kappa

On the other hand, the four-cylinder Kappa, derived from the pre-war Theta, was predictably successful, none of its innovations-an adjustable steering wheel and a central gear lever, for example-being hard to accept. The 1921 Dikappa was a sports version with overhead valves and an extraordinarily light body made of aluminum sheet on a walnut and acacia frame. Triota was military, TetraIota civil, and the 1922 Trikappa was the long-postponed V8, a 4.6-liter machine which boasted a claimed 98 horsepower.

The Lancia Lambda and Independent Front Suspension

It hardly mattered, in October of the same year the Lancia Lambda first saw the light of day at the London and Paris shows. This was Lancia's masterpiece, the car which best expressed all his engineering and artistic ideals. It was the car that confirmed the company's status for decades to come, the car which ratified a new line of reasoning in structural design, and the car which marked Lancia himself as a designer and engineer who had achieved true maturity. After a near accident, when a front spring broke while he was driving his mother in a Kappa, Lancia had determined to embrace the doctrines of independent front suspension by a system that should make his cars safe and more stable.

After pondering the problems of ship construction, he was tempted to embody the same principles of stress distribution by building a car in which the body and chassis were integrated for more efficient resolution of the forces to which it was subjected. After considering the fashionable and mistaken aesthetic ideals which prompted many engine designers to create slender space wasters of dubious rigidity, he determined to build engines that were short and stiff in all directions.

Lancia did not invent any of these features, but was the first man to combine all in one car, to put it into full production, and to persist with this combination throughout his life - and posthumously for as long as the company continued under the guidance of his son, Gianni. The torpedo-bodied touring Lambda was based upon a deep-sided sheet-metal frame that was in itself strong and stiff enough to carry all mechanical parts and support all suspension and other loads, while imparting to the body most of its structural strength. Its engine was a narrow-angle V4 with overhead camshaft, the whole being so short that the gearbox had to be located under the bonnet with it, prompting the strange new device of a tunnel along the centre of the uncommonly low floor to accommodate the drive shaft and gear-change lever.

The front suspension was by helical springs as the hub carriers slid up and down, on pillars that also acted as steering kingposts, and were supported by widely splayed tubular connections to the chassis. It was a system that, although varied in detail from model to model, was retained in principle by Lancia until 1963 and, apart from giving the independent movement of the wheels that Lancia sought, it also made possible a prodigious steering lock and steering that in feel was almost beyond comparison in its precision and delicacy.

As for the integration of this suspension system with the car as a whole, Lancia had his own characteristically big-hearted way of making sure that it was correct: at the end of the first series of test drives on the 1921 prototype, he ordered everybody out of the car and took the wheel of the Lambda himself - promptly driving it straight onto the kerb. In the ensuing scene of consternation and dismay, Lancia was noted rubbing his hands with glee. The virtues of this superb design were confirmed by the sale of 13,000 Lambdas in nine series between 1923 and 1931.

As with practically all later designs, the engine of the Lambda was increased in size as time went on, the capacity going up to 2.4 liters in 1926 with the seventh series and to 2.6 liters with the eighth, two years later. Four-speed gearboxes were standardised on the fifth series, a separate chassis became an option with the seventh and standard on the eighth and ninth, to cater for special bodies and in particular for taxi-cabs with a long wheelbase.

All the time the speed went up (the ninth series could do 78 mph), the roadworthiness of the chassis remained more than adequate for its performance. In 1928, this touring car came within sight of winning the Mille Miglia before a trivial accident eliminated it and although in Italy it was always accepted as a touring car, the Lambda was welcomed as a sporting machine in other countries on account of its excellent roadholding, prodigious brakes and unrivalled steering. Sales of Lancia's in England went from strength to strength, mainly because the Lancia, like all thoroughbred French and Italian cars until the 1950s, always had right-hand drive.

The Lancia Di-Lambda

The success of the Lambda gave the name of Lancia tremendous glamour, and the next model was awaited with great curiosity. It emerged as a big and heavy car with an eight-cylinder engine, called the Di-Lambda, the name more or less correctly indicating that it had two 2-liter Lambda V 4 engines, stuck together into a single unit. Seeing that the capacity was 4 liters, it might serve as a basic assumption, but the included angle of the DiLambda V was 24°, the widest that Lancia ever used.

His addiction to narrow V engines was understandable, as they were short and therefore stiff in all planes of the single main cylinder block, they could be crowned by a mono bloc casting embodying all the cylinder heads, and with evenly spaced bores and a separate crank throw for each connecting rod they could run smoothly without suffering agonies of bending or torsional flutter. Beyond these basic attributes, however, they had very little in common with one another; over the years, Lancia employed fourteen different angles, from the 24° of the Di Lambda to the 10° 14' of the Appia, and in fact there were three different angles for the three different sizes of Lambda engine.

Whatever the angle, they were always compact engines and, because they were always conservatively rated, they seemed to be able to stand hard driving for very large mileages; but they were not without their shortcomings, most notably in the porting of the complex cylinder heads in which the inlet and exhaust passages burrowed their ways in a convincing imitation of a rabbit warren, without much regard evidently being paid to charge heating, gas dynamics, or excessive shedding of heat to the coolant.

In all respects except its engine, the Di Lambda was something of a throwback, a big heavy car with a conventional chassis and the sort of flexibility (0 to 50 mph in top gear) that characterised too many other big expensive cars for the too few rich people surviving the current economic depression. It was also until 1972 the last passenger car to have a letter of the Greek alphabet as its name, the series continuing to be applied to commercial vehicles. Lancia wanted something that was not Greek but Italian, and somebody had the happy idea of naming subsequent cars after the ancient roads of the Roman Empire - roads which were themselves named after the daughters of the Emperors and Magistrates ruling at the time.

The Lancia Artena/Astura and Unitary Body Construction

The first of these cars was the Artena, a four-cylinder 2-liter car which, with the lightweight 2.6-liter V8 Astura, superseded the Lambda series in 1931. The a Astura was a favorite for body builders until 1937, but e before that the Augusta of 1933 appeared as a straw in Ir a new wind. It was perhaps the first really successful embodiment of an ideal that several manufacturers had long sought: an elegant, attractive, and completely convincing good small car. With it, Lancia reverted to unitary body construction, for the first time in saloon a form. In it, he perpetuated the idea of the compact s narrow V4-cylinder engine, and continued the tradition of steering precision and roadholding and braking ability, the enjoyment of which might bring an expression of bliss to the face of any driver not unbearably frustrated by the modesty of the engine's performance.

Nevertheless it was essentially a transitional design, enjoying deserved popularity while the factory readied their next car. This was to be one of Lancia's best, his second masterpiece, and his last. He demanded something bold, unconventional, streamlined, spacious, lively, stable, small, modestly engined and competitively priced. Falchetto (the engineer who had conceived the Lambda front suspension) concentrated on the body and, with the assistance of the aerodynarnicists and their wind tunnel at the Turin Polytechnic, he arrived, at a teardrop-shaped monocoque which Lancia promptly docked and flattened.

Lancia Engineers Sola and Verga and the Aprilia

Engineers Sola and Verga concentrated on the engine, and technical chief Baggi superintended the whole, Lancia himself having some preoccupations with a new 5-cylinder truck engine that made him unable to give the new car his undivided attention. Nevertheless, he subjected it to continuous scrutiny between the laying down of the project in 1934 and the final approval of the production prototype in June 1936. The car was the Aprilia, carrying the Augusta formula several steps further, with independent rear suspension by torsion bars, a well streamlined stressed-skin saloon body of pillarless construction, so that when all four doors were open each flank was completely unimpeded, and with a 1352 cc engine of 47 bhp in a car that weighed only 1800lb complete.

With a top speed of 80 mph, allied with a fuel consumption to the order of 30 mpg, and with handling qualities that qualified it to rank with the better sports cars of the time, the Aprilia laid down an entirely new set of standards by which all other small Cars might be judged for years to come. Of course, it was a tremendous success, returning to production after World War 2 and remaining on the market with its enlarged engine (up to 1½ liters in 1939) until 1950.

The Post War Lancia Ardea

Before the car went into production in 1937, Vincenzo Lancia died when not yet 56 years old. Naturally, the war brought its upsets, its moves, its bombings, its tragic destructions and its traumatic reconstructions. Eventually, the Lancia concern got back to normal and put on the market the little Ardea, a sort of miniature Aprilia with a 903 cc engine that had been introduced briefly in 1939. For 1946, it was graced with a five-speed overdrive gearbox, but all versions were disgraced, compared with the example of the Aprilia, by half-elliptic rear suspension. It was a nice little car in a gutless sort of way, and the Aprilia was still a marvellous creation by the standards of 1940, but with 1950 looming, it was time for something new, and with different people at the technical helm there was every possibility of achieving it.

Jano leaves Alfa and joins Lancia

The distinguished engineer Jano, who came to Lancia from Alfa Romeo (after earning his laurels at Fiat in the early 1920s) was now in charge of the experimental department. A young technician called De Virgilio conceived a new V6 engine of conventional 60° cylinder spacing and decidedly un-Lancia-like separate cylinder heads for each bank, and the founder's son Gianni Lancia as Chairman supervised the whole affair. Thus in 1950 the first entirely new Lancia since the death of Vincenzo appeared as the Aurelia.

As usual in Lancias, it started off with an engine that was too small for it, gearing that was too high for it, and a reputation that was if anything too good for it, but as the years went on it grew to 2 or even 2½ liters, it attracted new body designs, and the ravishing Gran Turismo version had its semi-trailing arm rear suspension replaced by a de Dion system to make it as outstanding a machine for fast long-distance road work as the Lambda had been in its time.

The Aurelia GT coupe was exceptionally influential in many ways. Its styling was practically as definitive as that of the slightly earlier Cisitalia coupe in shaping things to come, its physical size established norms that the industry later found it hard to alter, while its success in competition tempted Lancia to enter more objectively into the fray. With the active approval of Gianni Lancia, a proper competition car, known as the 020, was evolved, making some use of Aurelia GT experience. Capable of 155 mph, this car was a failure in the 1953

Mille Miglia and at

Le Mans, but thereafter its fortunes changed, and the Lancia works team began to score numerous successes, most notably in the

Targa Florio.

Lancia Motorsports and Formula One

At the same time, Jano was working on a much more advanced sports car, the 024, with a 3.3-liter engine developing 265 bhp, and with a chassis as unconventional as any. Lancia fancier had any right to expect, notably in the incorporation of large in-board front brakes. These formidable cars were tremendously successful, finishing I, 2, and 3 in the Carrera Panamericana in which a supercharged Aurelia B20 had scraped a fourth place a year earlier. Then the 024 won the Tour of Sicily, the Targa Florio and the Mille Miglia, as well as taking part in a number of other events, sometimes with the engine reduced to 3.1 liters, sometimes with a larger 3½-liter version, which evolved into the 025, with five-speed gearbox, short wheelbase and an unladen weight of only 12 cwt.

Had Gianni Lancia been content with this, he and the firm's sporting enterprises would have enjoyed ample justification. Unfortunately, he succumbed to the temptation to go the whole hog and enter a team of Formula One cars in the Grand Prix races of 1954 and 1955. With this object, Jano produced a most distinctive machine, with a V8 engine taking structural loads from the front suspension, with a wide track, a short wheelbase and an unmistakable shape created by outboard pontoons (acting as fuel tanks) filling the space between front and rear wheels. As a technical exercise, it was fascinating, but as a racing car it was not entirely perfect.

With its masses unconventionally distributed, the Grand Prix Lancia had very low polar moments of inertia in yaw and in pitch, but a high one in roll, calling for firm suspension and making it interesting that the rear dampers were connected by a balance beam so as to be ineffective in roll. The car was noted for having rather jittery roadholding, but its basic stability, braking and power (despite a shockingly rudimentary exhaust system) were hardly in question, and after prolonged teething troubles it eventually joined the lists late in 1954 and proved to be as fast, although not as reliable, as the W196 Mercedes-Benz that then dominated Grand Prix racing.

What followed next came as a shock, even to those sufficiently informed for it to come as no surprise. In July 1955, Lancia handed its Formula One machines to Ferrari - who promptly set about altering them until they were as little like Jano's original ideas as possible - and washed their hands of motor racing. The company sought to make good the deprivations of racing with a flurry of bread-and-butter designs. Already there was the little Appia, which stood in the same relationship to the Aurelia saloon as the Ardea had to the Aprilia.

1956 brought the revolutionary Flaminia, the first to depart from tradition with wishbone front suspension, although in its basic engine and transmission it revealed a strong kinship with the Aurelia. Even more dissident was the Flavia, which appeared in 1961 as the work of Dr Fessia, recruited to Lancia after a distinguished career that had been marked by his design of the pre-war Fiat 500 Topolino. The Flavia was a front-wheel-drive car with a horizontally opposed four-cylinder engine, disc brakes, an all-synchromesh gearbox (Lancia eschewed synchromesh until a very late stage, and the quality of the gearchangein its earlier dog-boxes was ample justification for doing so) and leaf-spring suspension of a dead-beam rear axle.

The Lancia Fulvia

In 1964 the Appia was replaced by the Fulvia, which echoed Flavia practice, and was eventually developed in sporting versions. By this time, the company had made a fairly good recovery, building 40,000 cars in 1966, and once again they were tempted to go racing and rallying. They did so with no little success, the Fulvia in particular producing impressive results in the major international rallies. And yet in spite of all this success, or because of the cost of attaining it, the firm was once again in trouble, and mounting debts forced them to sell out to Fiat in November 1969.

Fiat were characteristically generous in their take-over, allowing the ailing firm plenty of time to get themselves reorganised and reasonably profitable. They were equally characteristically unwilling to stand any nonsense, and the cultivation of those odd designs that were not as clever as they purported to be was firmly curtailed. Instead, Lancia were offered versions ofthe Fiat 132 engine which was better than it ought to be and, with the aid of this and some front-wheel-drive ideas of similar provenance, Lancia launched a new car, keeping some semblance of self-respect by making it to high quality standards and once again resorting to the Greek alphabet for nomenclature.

In 1977, The Gamma stood at the head of Lancia's range. Introduced in saloon and coupe forms at Geneva 1976, and featuring an all-new 2.5-liter flat four engine, the Pininfarina-styled cars were favourably received by press and public. Probably the final statement of the Beta theme - the mid-engined Monte-Carlo-was also winning friends in 1977, a testimony to Lancia's continuing endeavour to produce cars of charm and excitement, and proof of their success.

The Lancia Stratos

The new Beta saloon, and its later coupe and HPE derivatives earned a good deal of praise and (which may be more to the point) provoked no apparent resentment. Another gift in the Fiat dowry was their Ferrari-based Dino V6 engine. Lancia had on the stocks just the car to exploit it, a short and squat super-sporting stream liner called the Stratos. The production Stratos of 1973 was not nearly as futuristic as the impractical little 1971 prototype, but merely a road car embodying the best of then current racing-car practice.

The “Stratos” was designed with one objective in mind – rallying. Gianpaolo Dallara, who had worked for both Lamborghini and de Tomaso, is credited with doing the majority of the development work on the car, while the styling and structural manufacture were completed by Bertone. As used in the Stratos, the Dino engine was transversely mounted behind the seats, and was good for 190bhp at 7000, all from a reasonably small and lightweight 2418cc engine that drive the rear wheels through a Ferrari Dino five-speed gearbox. The Stratos front and rear body sections could be swung completely up and out of the way, providing access to the all-independent suspension, and four-wheel disk brakes.

The Lancia Delta S4

During 1974 and 1975, approximately 500 Stratos were built to meet homologation requirements as a Group 4 competition machine, and once approved it dominated rallying more than any other car before it. The 'works' team won three consecutive World rally championships - 1974, 1975 and 1976 - and in 1978, Stratos cars won 13 national and international events, all round the world. In the meantime, Fiat had produced a mid-engined sports coupe which they then donated to Lancia for production; this was the unit-construction “Monte Carlo”, with coachwork by Pininfarina. The “Monte” used a transverse mid-mounted twin-cam Fiat four-cylinder engine of 1.6, 1.8 or 2.0 liters with integral five-speed transmission.

In the USA it was known as the Scorpion and in all markets it was sold with either a fixed roof or roll-back 'convertible' top. The last of these cars were built in 1983/84, after a two year lay-off in the late 1970s to sort out handling and quality problems. For rallying purposes, however, the Stratos was succeeded by the Lancia Rally coupe, which looked rather like the Monte Carlo, but was almost entirely special except for using that car's center section. Only 200 were produced, with tubular front and rear sub-frames, a longitudinal instead of transverse engine mounting, and a supercharged (not turbocharged) engine.

The first car was shown at the end of 1981, the 200-off run was completed by mid-1982, and the car started winning events later in the year. In 1983 it distinguished itself by winning the Monte Carlo rally, and going on to take the World Rally Championship for Makes. In road-car tune, the 1995cc 16-valve engine was good for 205bhp, with up to 325bhp at 8000rpm available in fully-tuned form.

Also see: Lancia Car Reviews |

Lancia History (AUS Edition)