|

Jaguar

|

1922

- present |

Country: |

|

|

William Lyons

William Lyons began his business life in Blackpool, England, in partnership with Bill Walmsley. They set up the Swallow Sidecar Company in 1922 to manufacture sidecars for motor cycles, but Lyons' flair as a body stylist soon found expression in the Swallow-bodied Austin 7, after which he turned out a succession of cars based upon mechanical components made by Standard, but so well styled and so competitively marketed that SS Cars, as the company became known in 1935, never looked back, until 1945.

Swallow Special or Standard Swallow?

There has been argument as to whether the initials stood for Swallow Special or for Standard Swallow - and until his death in 1985, Lyons never elaborated. In any case, by 1945, with World War 2 uppermost in everybody's memories, the initials were more likely to be associated with the Schiitzstaffel, and the name of the company was changed to Jaguar Cars Limited.

Power, Speed and Courage

The Jaguar title was supposedly chosen by Lyons from a list of 500 animal names, because it had power, speed and courage. The name-change made no difference to the way Lyons ran the company. He was completely autocratic: there was not one board meeting until 1965, despite the fact that the company had acquired Daimler in 1960, Guy Motors in 1961 and Coventry Climax Engines in 1963.

During 1965 negotiations got under way for the merger of Jaguar Cars with the British Motor Corporation (BMC); when eventually these talks reached their fruition, it was only on the strict understanding that Lyons remained virtually as autonomous and autocratic as before.

Although he remained very quiet and gentlemanly in his conduct (he never addressed even his Vice Chairmen by anything other than their surnames), he was extremely strong in business. When British Motor Holdings (the company which represented the merger of BMC and Jaguar) were in turn acquired by Leyland to form part of the new BLMC group in 1968, Lyons became the deputy chairman under Stokes and, during the dealings leading to the completion of the merger, he is recorded as having addressed the board in terms so powerful that they were, by agreement, left out of the minutes of that meeting.

Jaguar, in effect, belonged to Lyons, and he would not tolerate anything that challenged his control. The name Jaguar was already well known and closely associated with the company's products when it was adopted in 1945. It had been applied to a series of SS models introduced in 1936 and popularly acclaimed as a kind of poor man's Rolls-Bentley. In 1945, the Jaguar that was prepared for production in the following year was substantially the same as the pre-war design, subject only to the adoption of hypoid gearing in the back axle.

There were three versions, with engines of 1½ , 2½, or 3½ liters, the two larger six-cylinder versions being mounted in chassis of 10 foot wheelbase, and the four-cylinder engine in one that was eight inches shorter. Before World War 2 all these pushrod engines had been made for SS by Standard; soon after it, Standard's Managing Director, John Black, told Lyons that, with his company's commitment to the new Vanguard car the production of engines for Jaguars could not be maintained.

Offering to sell the necessary plant to Jaguar, he apparently had second thoughts upon the arrival of transport for the equipment and a cheque to pay for it; but Lyons, having secured for himself yet more independence, was not one to surrender it again, being content merely to let Standard continue with the four-cylinder engine, for which he had no long-term plans. As might be expected from a company which owed its commercial success to concentrating on appearances, the mechanical realities beneath the fashionably glamorous Jaguar bodies were essentially humdrum.

A simple girder chassis carried beam axles' on half-elliptic leaf springs, the modestly rated engines drove the car through four-speed gearboxes having synchromesh on the upper three of some well spaced but not so well engaged ratios, and the car was stopped by Girling rod-operated brakes. None of this was as important as the fact that in 1946, the smallest of the three Jaguars could be bought for UK£684, and the largest for UK£991.

1934 SSI fitted with an in-line 2143cc six cylinder engine.

1934 SSI fitted with an in-line 2143cc six cylinder engine.

SSI Tourer which featured four-seater bodywork.

SSI Tourer which featured four-seater bodywork.

1936 SS 100, capable of 100 miles per hour, it was fitted with a 2.7 liter six-cylinder engine.

1936 SS 100, capable of 100 miles per hour, it was fitted with a 2.7 liter six-cylinder engine.

1938 SS 100, which was fitted with a 2.7 liter engine.

1938 SS 100, which was fitted with a 2.7 liter engine.

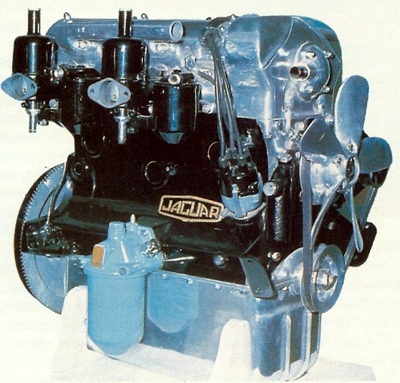

This is the XK 100 engine, as displayed at the 1948 London Motor Show. The engine was a 4 cylinder 2 liter unit - the popularity of the XK 120 meant the XK 100 would never be put into production.

This is the XK 100 engine, as displayed at the 1948 London Motor Show. The engine was a 4 cylinder 2 liter unit - the popularity of the XK 120 meant the XK 100 would never be put into production.

1951 XK 120 Coupe.

1951 XK 120 Coupe.

Modified XK 120, powered by a 3442cc 190 bhp version of the XK engine.

Modified XK 120, powered by a 3442cc 190 bhp version of the XK engine.

1949 Jaguar XK 120.

1949 Jaguar XK 120.

1957 XK 150 Convertible.

1957 XK 150 Convertible.

D-type Jaguar, which won the Le Mans three times in succession, from 1955 to 1957.

D-type Jaguar, which won the Le Mans three times in succession, from 1955 to 1957.

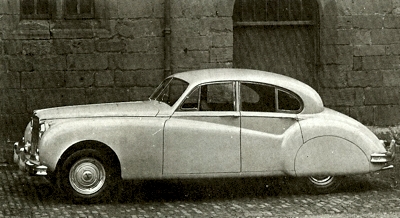

1955 Mk VII Jaguar.

1955 Mk VII Jaguar.

Mk. 2 Jaguar, which was available with either a 2.4 liter or 3.8 liter engine. The car proved popular with the British Police, because of its power to weight ratio.

Mk. 2 Jaguar, which was available with either a 2.4 liter or 3.8 liter engine. The car proved popular with the British Police, because of its power to weight ratio.

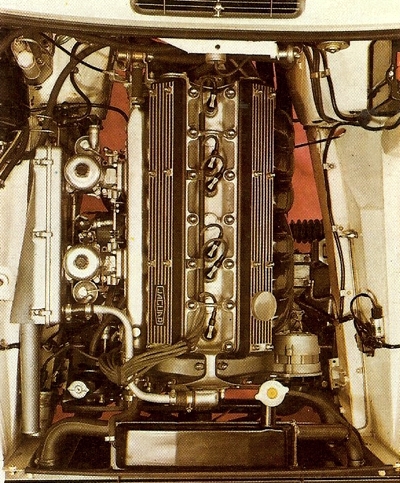

The XK Engine - beautiful from any angle.

The XK Engine - beautiful from any angle.

The Jaguar XK-E or E-Type was introduced in 1961. It was priced well below the competition, and retained the 3.8 liter engine.

The Jaguar XK-E or E-Type was introduced in 1961. It was priced well below the competition, and retained the 3.8 liter engine.

A 1969 Jaguar XJ6. It was available with either a 2.8 liter or 4.2 liter engine, and was a very good car, despite quality control problems that were to surface during the 1980's.

A 1969 Jaguar XJ6. It was available with either a 2.8 liter or 4.2 liter engine, and was a very good car, despite quality control problems that were to surface during the 1980's. |

The "Interim" Jaguar Mk V

No sooner was the production of these cars established again than adventurous plans were made for future cars. Some massive re-tooling was indicated, and an entirely new engine prepared; and all this would take more time than the pre-war designs could be expected to remain attractive to the customers. An interim design was therefore developed, which came onto the market in 1949 as the Jaguar Mk V, with the same choice of six-cylinder engines in a chassis brought mildly up to date by the incorporation of independent front suspension and hydraulic brakes, while the body was elaborated and smoothed-faired headlamps and a new style of fenestration being the most important features.

The cars were not particularly fast, not very responsive and, by the standards of the kind of cars they purported to be, they were not even very good; but neither were they very expensive, the 2½ -liter Mk V costing only UK£1247 in 1950 which seemed good value to British customers considering the price of £3000 for a 2-liter Bristol or even more for a 4½ -liter Bentley. By this time, the world had already been given a taste of the new generation of Jaguars that was to come, and for so long to endure.

The Jaguar XK 100 and XK 120

It was at the London Motor Show of 1948 that the XK 100 and XK 120 sports cars were first publicly shown. The 100 was to be a four-cylinder, 2-liter affair that would do 100 miles an hour or so, the 120 being a six-cylinder 3.4-liter version that would do 120 miles per hour; but they looked identical, and at the time it seemed improbable that either could have been improved by looking different from the other. At a time when the average sports car looked anything but attractive, the XK 120 (the 100 was never seen again) was as smooth and svelte a creation as ever bore witness to the fluency of Lyons' styling, even though the design was fairly obviously derived from that of the 1940 Mille Miglia 328 BMW.

The engine mattered even more than the body, and much more than the chassis, which was merely sturdy although it used torsion bars for the front independent suspension wishbones. Engineering Director William Heynes, with Waiter Hassan and Claude Baily, put more work into the engine than into the whole of the rest of the car; and the fact that the engine was still in production decades later shows how worthwhile the work was. At least as much as the body design, it brought entirely new standards to the production sports car, while nevertheless remaining quite old-fashioned in its basic elements.

The 3.4 Liter Engineering Masterpiece

In some respects the 3.4-liter engine was similar to those used in the 1930 Grand Prix, with twin overhead camshafts, a long stroke and a robust crankshaft generously furnished with a main bearing between each two adjacent crank throws. The hemispherical combustion chambers in which the two inclined valves were seated (Heynes presented a famous paper on the virtues of this shape) combined with well-shaped inlet and exhaust tracts to ensure high performance, and only the tremendous weight of the massive iron crankcase would have disqualified it from being competitive as a Grand Prix engine twenty years earlier.

As it was, tuned for the revoltingly bad petrol of the times, the XK 120 engine developed 160 bhp, and could safely be run up to 6000 rpm. This was an extraordinary power output for a two-seater in those days, and the effectiveness of the engine/body combination was demonstrated by a timed run on the motorway from Jabbeke to Aeltre in Belgium, when an almost standard XK 120 was timed at over 132 mph - after which it was driven with past the timekeepers and observers at 10 mph in top gear.

It was a wonderful engine - although it was not without its faults, the vast iron block soaked up a great deal of heat that the engine could hardly dissipate (you could burn your fingers on the dipstick) and its lubrication system had the unfortunate habit of delivering more oil to the camboxes in the head than the return system could handle, with the result that the surplus simply had to find its way past the valve guides into the combustion chambers. The sump could be emptied in the course of a fast run up the freeway; but nobody minded at the time.

In fact, it was not intended that many XK 120s should be built. The 100 was forgotten almost as soon as it was displayed; the four-cylinder XK engine had been usefully employed in Goldie Gardner's record-breaking MG streamliner to take some international speed records in the un supercharged 2-liter class, and then quietly shelved. The six-cylinder engine was intended to power a big new Jaguar saloon, and the sporting XK 120 was no more than a small series of aluminum-bodied cars that would get the engine into production, earning money and kudos, while the saloon was readied.

Peter Walker, Leslie Johnson and Prince Birabongse

But at

Silverstone in 1949 the XK 120 ran in the Daily Express one-hour race for production cars. There was a team of three two-seater Jaguars, one in red for Peter Walker, one in white for Leslie Johnson, and one in blue (with touches of yellow to complete the Siamese royal palette) for Prince Birabongse. It was an Allard that led away from the run-and-jump Le Mans start, but between the first and second corners it was swamped by the team of Jaguars rushing past to lead the race in disciplined line-ahead formation.

The demonstration was convincing; the cars might have rolled like yachts, but they still seemed to get around the corners pretty well, and their speed down the straights was blisteringly fast. In fact, one of the tyres on Bira's car managed to blister its inner tube (an ordinary one had been fitted inside the Dunlop racing cover on one of the rear wheels) and the car retired three-legged onto the grass where its jack proved useless. So the hour ran out with Johnson winning from Walker, a comfortable distance ahead of the 2-Iitre Bristol-engined Frazer-Nash that was there to show the punters how a proper sports car should go around corners.

This impressive performance did wonders for morale at a time when it was universally accepted that Britain could not make a proper racing car. However, even in sports-car racing, it would be seen that an hour around

Silverstone was one thing but 24 at Le Mans was a very long way indeed. One of these Jaguars was brought up to third place for a while in the 1950 race before retiring with its single-plate clutch disintegrated, while Johnson managed fifth place in the Mille-Miglia that year, a much better effort.

A Steel-Bodied XK 120 For The American Market

For a car that a was never supposed to go into quantity production, it was an unexpected effort - but the demand for the XK 120 was overwhelming, and Lyons sanctioned a steel-bodied version that was to open up the American market for the company and establish the Jaguar reputation so firmly that, roll and brake fade and soggy low-geared steering notwithstanding, nobody would hear a word said against it. Not until 1955 was the XK 120 updated, and the changes then were superficial; heavier bumpers and more extensive chrome altered the appearance little, the fixed-head coupe profiting more than the open roadster from the change, and the new drophead coupe looking uncommonly graceful.

The Jaguar XK 150

By this time the quality of petrol had improved, and the output of the engine could be raised to 190 bhp at 5600 rpm - and it remained pegged at that level two years later when a rebodied XK 150 came along. The XK 150 was later to get disc brakes, which at last made it feasible to use that prodigious performance fully on winding roads. Those disc brakes had made Jaguar famous in 1953, when they helped the XK 120 C (or C-type) cars to win Le Mans for the second time, despite the greater speed and power of the rival Ferraris.

The Jaguar C-type

The C-type had already won Le Mans when it made its competition debut in 1951 - inspired by the performance in 1950 of the supposedly standard but actually very specially prepared XK 120 there. The chassis of the C-type was based on generously drilled channel-section members with a triangulated tubular super-structure, while the front suspension was largely standard, the rear axle was carried in a simple but ingenious three-link mechanism sprung by a transverse torsion bar anchored in the middle. The engine had been tuned by conventional methods to produce 210 bhp at 5800 rpm, sufficient with a light and pretty streamlined body to give it a maximum speed of about 150 mph.

Peter Whitehead and Peter Walker take the 1951 Le Mans

Three of these cars went to Le Mans in 1951, two retiring because of oil-pipe fractures, but the third, driven by Peter Whitehead and Peter Walker, surviving to win by 77 miles from a Talbot at a record average speed of 93.5 mph, and with a new lap record to the credit of one of the other Jaguars at a speed of 105.24 mph. It was a great occasion for British devotees of motor sport, giving Britain its first Le Mans win since the Lagonda success of 1935, and it did everything that was intended in the way of publicising Jaguar competence. Any remaining doubts were dispelled by the C-type's victory later in the year at the TT, while more ordinary XK 120s took a gold cup in the Alpine Rally and ran for 24 hours at an average of 107 mph around the banked track at Montlhery.

So successful was the 1951 season that Jaguar were tempted to treat the following year a little too casually. A half-hearted attempt at the Mille Miglia, in a C-type equipped with the first disc brakes to be used by Jaguar, was a failure. While driving the C-type in Italy, however, Stirling Moss was given food for serious thought when his car was passed easily along a straight by one of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupes. When he reported this to the Jaguar factory, it was agreed by all concerned that something had better be done to increase the top speed of the Jaguar lest it suffer similar humiliation at Le Mans.

Trying To Catch the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL

In great haste, a new body was devised with longer bonnet and tail, and the cars were sent off to France, only to prove during practice that the smaller radiators fitted in the shallower noses of the new cars were inadequate. Despite the substitution of standard radiators in two of the cars, producing hideous bulges in the bonnet tops that had been so carefully profiled, the entire team succumbed to overheating early in the race. A few weeks later (with standard bodywork again), the factory team was once again roundly defeated in the nine-hour sports-car race at Goodwood, but when the C-type was put into production and appeared in the market place at a basic price of UK£1495 (plus tax) in August 1952, there was no shortage of willing customers.

Road tested by The Motor, the C-type, in its production form, accelerated from rest to 100 mph in 20.1 seconds. The factory team of C-types that returned to Le Mans in 1953 were faster and a lot better prepared. Once again, they had to contend with formidable Ferrari opposition, but what the Jaguars lacked in the ability to go (although the power output had risen to 220 bhp with the aid of triple twin-choke Weber carburetors) they made up for in their ability to stop: Dunlop disc brakes were fitted to all the team cars, allowing them to leave their braking dramatically later than the drum-braked Italian cars at the end of the long straights.

The Jaguar Mk VII saloon

With a five-link rear-axle location and flexible fuel tanks to forestall any repetition of failures noted in the past, the team of three cars finished first, second, and fourth, with a privately entered car in ninth place, and their honour was popularly vindicated. Although the disc brakes that made it all possible were not to feature in a quantity-production Jaguar until 1958, the car that most needed them from the outset was introduced in 1951, in the same year as the C-type appeared. This was the Mk VII saloon, the car for which the XK engine had been prepared, and for which it had mainly been intended.

A Mock Mk VII Wins At Silverstone

In comparison to its sporting contemporaries, the Mk VII was big and bulbous, with a 10 ft wheelbase and a vast heavy body. It was opulent in all its interior appointments and almost obscene in the grossness of its exterior contours. Despite its great weight, its soft suspension, its barge-like proportions, and its severely taxed brakes, the Mk VII could go very quickly, thanks to that wonderful engine, and quietly. Nor was it beyond the wit of Jaguar's engineers, despite the distractions of a move to larger factory premises in Allesley, on the outskirts of Coventry, to produce a firmly sprung, highly tuned aluminum-bodied and substantially lightened facsimile version which swamped the opposition in the production-car race at

Silverstone, successfully giving the public the false impression that this Mk VII was the finest and fastest saloon on the market.

In any case, most customers did not buy it to go fast, but to be comfortable. By 1955, the Mk VII had succeeded well enough to develop into the VIII, now with 190 bhp at its disposal and with a basic price tag of UK£1616, £340 more than in 1951. Another two years, another couple of hundred pounds, and another 20 bhp, not to mention a great proliferation of chromium beading and two-toned paintwork, made it into the Mk VIIM, with a curved windscreen suppressing some of the lines of old age evident in the angular two-piece screen of the earlier models.

The really significant change came in 1959 when the Mk IX acquired Dunlop servo-assisted disc brakes on all four wheels, and an enlarged XK engine of 3781 cc, from which 220 bhp was claimed. Not all these horses might reach the rear wheels, as by now many of these cars were fitted with automatic transmissions, comprising an epicyclic gearbox and converter coupling that took its toll of the torque it transmitted. Automatic transmissions were first fitted to the Mk VII as an optional extra, and this choice remained open to the buyer of virtually any production model thereafter.

The one that could least afford an auto transmission was the 2.4 saloon, a complement to the grandiose Mk VII and some sort of compensation for the loss of quasi-sporting attributes lamented with the passing of the Mk V and its predecessors. The new engine displacement of 2483 cc was arrived at by shortening the stroke of the XK engine from 106 to 76.5 mm, and the corresponding shortening of the cylinder block made a welcome reduction in the weight of cast iron in the nose of the tubby little car. Unfortunately, the engine did not respond as well as had been expected to the shortening of stroke, its power output being a rather undistinguished 112 bhp at 5750rpm.

Since the car was by no means light in weight, the engine could not propel it at any great speeds, and since it was particularly narrow in the rear track (where the wheels were enclosed by spats, as had those of the early XK 120) and the road holding was mediocre, it was probably just as well. To be fair to the car, one example, driven by Paul Frere, won the touring class of the Belgian production-car race at Spa in 1956, but it pays to remember that the factory-entered saloons of this period were as far from standard as the regulations of each event would allow. The special specification of the racing Mk VII, has already been mentioned, and that of the Mk VII which won the Monte Carlo Rally in 1956 might be arrived at by inspired guesswork.

In competition, Jaguar did not believe in accepting unnecessary handicaps. In fact, it was because of a handicap system, that applied to the results of the Dundrod TT, that the little 2½ -liter engine was first tried in competition, in an early version of the beautiful and otherwise generally successful D-type competition car. Without a doubt the loveliest, the fastest, and (after the end of its production run) the most cherished Jaguar, the D-type is even more important to the critical student of the make's history as the Jaguar which, better than any other, demonstrated the ability of the firm's engineers to do things properly.

Malcolm Sayer and the D-type

Arguably the most accomplished of these gentlemen was their ex-Bristol aerodynamicist, Malcolm Sayer, whose work on the D-type earned the unstinted approval of the experts at Farnborough. The shape he created for the car, basically elliptical in longitudinal and transverse sections, was an evolved form of the special body built for record-breaking purposes in 1953 - the record-breaker being known as the C/D prototype which reached nearly 180 mph in October of that year when driven by Jaguar's well known tester, (and occasional racing stand-in) Norman Dewis.

The refined contouring of the final D shape did more than reduce aerodynamic drag: it also encouraged the adoption of constructional techniques that had hitherto been foreign to the firm. The centre section was an elliptical-section tub of stressed 18-gauge magnesium-alloy sheeting, suitably stiffened by bulkheads at front and rear and welded to a multi-tubular frontal frame carrying the engine and front suspension. In 1954, when the D-type first appeared at the Le Mans practice weekend, the engine was the well proven 3.4-liter XK now tuned to develop nearly 245 bhp. To get it into the surprisingly low D-type body, it had' been converted to dry-sump lubrication and further lowered by being canted eight degrees on its side.

The front suspension and the rack-and-pinion steering came without much change from the then new XK 140, and the rear suspension consisted of a five-link location for the live axle, sprung as in the C-type. Between that axle and the special racing clutch at the back of the engine was an entirely new four-speed gearbox, designed and made by Jaguar with synchromesh on all forward ratios. The Moss gearbox that had served in all previous Jaguars, and was to be a notorious feature of ordinary production models for some years to come, was very strong, but in other respects rather nasty, with a hideously slow and heavy change that was not improved by the rapid decay of the synchromesh serving the topmost three ratios.

The Plessey Pump Servo Assistance

Behind this new gearbox was an interesting little detail, often overlooked - a Plessey pump driven by the output shaft to provide servo assistance for the disc brakes, an example of powered hydraulic application. This meant that Jaguar pre=dated the classic

Citroen DS design by no less than twelve months. In 1953, it had been the Jaguar's ability to stop that had brought it victory at Le Mans and earned it such fame. In 1954 things were different: thanks to Sayer's body, the new D-type was the fastest thing yet seen on the roads of the French circuit, being timed on the Mulsanne straight at a new record 172.97 mph.

But it was not sufficient to win the race, as all three team cars had troubles and only one survived, fighting through foul weather to finish the 24 hours just 105 seconds behind the winning 4.9-liter Ferrari. The fact that the stupendously powerful Italian was nearly 13 mph slower than the D-type proves how well the latter was shaped. In the twelve-hour race at Reims, a month later, D-types finished first and second, despite opposition from Ferrari and Gordini. It was in the D-type's next venture, the TT in Ulster, that a 2.48-liter engined car was tried, finishing fifth and presumably supplying some kind of reassurance for the production engineers preparing the 2.4 saloon for 1956.

Before then, there was to be another season of earnest competition endeavour, and the prelude thereto consisted of some furious redesign and development of the D-type. The redoubtable engine itself had not been without its problems, but the most notable change was a new cylinder head, made to accommodate larger valves by increasing the included angle between the banks of inlet and exhaust poppets from 70 to 75 degrees. This change that was instrumental in raising the output from 245 to 270 bhp, still at 6000 rpm. This was as much as the 2.4 could run up to in safety, developing 193 bhp for the 1954 TT.

What caused Jaguar more concern than engine performance, however, was the car's vulnerability to accidental damage. A lot of time had been lost at Le Mans, for example, in repairing the ravages of an excursion into the sand banks. Some very intelligent alterations were accordingly made so that localised damage could quickly be repaired, especially in and around the nose of the car, where the radiator and other major elements of the cooling system were carried in their own independent sub-frame.

The best change of all was in the design of the tubular half-chassis which carried the engine and front suspension ahead of the stressed-skin tub amidships: in place of the original light-alloy tubing that was made integral with the tub, and which partially penetrated it in rather inept fashion to constitute a spinal reinforcement connecting the engine with the rear bulkhead, an entirely new steel sub-frame was built up in a triangulated shape of ultimate elegance, designed so that it could be bolted to, and unbolted from, the middle portion of the car, as an aid either to survival or to cannibalisation.

More apparent and almost equaly beautifully done was the reshaping of the body's contours. A longer nose was designed to give cleaner air entry, a new tail fairing with integral fin replaced the headrest and bolted-on fin of the previous year, and the. wraparound windscreen was extended to merge with this fairing, to create a sort of conning tower that was about as well streamlined as an open car could hope to be. All told, the 1955 D-type was a beautiful thing, improved even further by the adoption of 16-inch wheels of light-alloy, in place of the 17-inch ones used the year before.

Given the number of changes, most predicted the 1955 season would be a good one for the D-type. The first major victory was Le Mans, which was its prime objective, but it is arguable that it won because of the withdrawal of the Mercedes-Benz team after the ghastly accident that occurred there, and which cast such a shadow over subsequent races that in truth nobody could have had a really good season. Nevertheless, Jaguar went on trying at such venues as they were able, but elsewhere than at Le Mans the D-type was trounced by opposition from Mercedes-Benz and Aston Martin.

In fact, it was beginning to look as though the D-type was so highly specialist that it was fit for Le Mans and precious little else. There was certainly no question of entering this fragile little beauty for something as stern and uncompromising a test of road-going ability as the

Mille Miglia, while on closed circuits that could not offer the billiard-table smoothness of the Le Mans surface the Jaguar seemed to lack something in the roadholding department. A necessary corollary of its shape was that it was narrow in the track, which meant in turn that its suspension movement had to be somewhat limited, and Dunlop had to do a lot of hard work in developing tyres to suit the car.

Still, it must be recognised that Jaguar were not campaigning a team of cars for the sake of enjoying motor racing, but for the sake of publicity; and all the other sports-car races of the year could not, when put together, equal in importance the publicity value of the 24-hour race at Le Mans - which is what the D-type won in 1955, as Jaguar had in 1953. The trouble with establishing such a pattern is that it tends to become habit-forming, and true to form Jaguar had a pretty disastrous year in 1956. The only thing of any consequence that the factory cars won was the 12-hour event at Reims - but by that time, there were a lot of D-types about, a production line having been established to build a total of 67.

It was one of the cars sold to private owners (at what must have been a nominal price of £3878, with a 55-page handbook thrown in) that, entered by the Ecurie Ecosse, won the Le Mans event alter the works' cars had run into trouble, two of them crashing and the third having trouble with its new fuel-injection system. The Scots did the same again in 1957, when the factory had withdrawn from official participation, and this was at a record average speed that was not to be beaten until 1961. This time the car had an engine of 3.8-liters displacement, achieved by the increasing the cylinder bore by 4 millimetres.

American Tuners Prepare a D-type for Sebring

This was first tried by American tuners, preparing a D-type for

Sebring, and it served to raise the bhp to 306, which was 30 more than the 3.4-liter engines of the previous year. The Americans, who had numerous associations with Le Mans, dating back to the 1920s, but had never shown any enthusiasm or aptitude for less-refined forms of torture, such as the Mille Miglia, were very keen on the D-type. In an effort to widen the car's appeal, Jaguar embarked on a batch of cars to be known as the XK SS, tantamount to a D-type with full width windscreen, interior trim, and reasonably comprehensive road going equipment for the US market.

Sixteen of these cars were completed before the whole service department and the D-type end of the factory were destroyed by fire in February 1957. Jaguar could hardly be criticised for withdrawing from racing in these circumstances, especially when they had so many important developments coming to fruition in their bread-and-butter range. Of these, by far the most important was the evolution of the little 2.4-liter saloon, which had appeared the year before. It was not long before its rear spats disappeared to make room for an axle of sensibly wider track.

With the increased stability that came from this, it was little longer before the same compact and handsomely curvaceous car acquired the regular 3.4-liter engine, which by now was attributed with the ability to give 210 bhp, as did the contemporary Mk VIII saloon, profiting from the improvement in the quality of petrol available. Little more time was to pass before the body was revised, most notably by the enlargement of the rear window, and a number of refinements created what became known as the Mk 2, at first with 2.4 and 3.4-liter engines. By 1960, the car could also be had with the 220 bhp 3.8-liter engine, and in all forms was braked by Dunlop discs on all wheels.

The Mk 2 was a phenomenally successful Jaguar. Anybody reluctant to spend a fortune could hardly conceive of a better proposition among sporting saloons, combining as it did the legendary XK engine with up-to-date brakes and traditional standards of interior decor. Enthusiastic motorists loved it; so did the police, who found that in motorway service, the engine would run for a quarter of a million miles and so did the club racers, who found that the 3.8 version was able to dominate saloon-car racers in a wonderful display of roll and slide. It was a car that went with pride and with avarice, prompting envy and the sour-grapes syndrome among those who were not honest enough to admit that they would like to have one.

The Jaguar Mk X

Thus, 'Jag' became an accepted term in English usage, both in the UK and here in America. Compared with the crisp manners and phenomenal performance of the larger-engined Mk 2 cars, the bulbous Mk IX no longer seemed so magnificent. The time had come for a new big car to deal with the upper-end of the market, and when the

Mk X was introduced, in 1962, it became apparent that the Mk IX was in truth as much of a stop-gap as it felt. Rounder in its contours, wider in its track, more expansive in its interior, and in every respect more luxurious than ever, the Mk X was distinguished by a very fine piece of independent rear suspension, in which the geometry of wheel motion was that dictated by double unequal un parallel wishbones, but in which the duties of the upper wishbone were undertaken by the universally jointed half-shaft, devoid of slip joints so that the universals could define the motion of the hub carrier.

The Jaguar XK-E

Within a couple of years, the suspension of the Mk X had also been grafted onto the rear of the Mk 2 saloons to create the S types in 3.4 and 3.8-liter forms, softer-riding and bigger-booted but less sporting successors to those compact cars that had set so many new performance standards in their time. Hardly anybody noticed. Since the year before the birth of the Mk X, the word 'Jaguar' had acquired a new connotation. And then came the

XK-E, or as it was known in the UK, the

E-type. It seemed the entire motoring felt an awe that it had not felt since the unveiling of the original XK 120.

Of course the ones you bought from your local dealers could not match the 150 mph reached by the carefully prepared cars road-tested by the motoring journals. It was cheaply made and finished, and it got very hot inside, and the brakes were a bit problematical when cold, and the seats would not accept anybody taller than about 5 ft 9 inches. It did not matter; here was a refined road going son of the D-type, a car that made the higher-priced Aston Martins and exotics seem over-priced, a car that was quite simply the most glamorous and eye-catching object you could possess.

Lots of people bought it simply as a cosmetic, and were content to drive it slowly. Lots more bought it as an ego booster, and discovered in a few frightening and perhaps final seconds of unfamiliar experiences that they were not fit to do otherwise. For their part, Jaguar discovered that most of the people who could afford their cars could also afford to waste time, but on the other hand were not well-endowed either with co-ordination or energy. The 265bhp (a gross figure, as Jaguar's commonly were) 3.8-liter engine was supplanted in 1965 by a 4.2-liter version in the E-type and the Mk X.

Extensive redesign of the cylinder block relocated the bores so that they could be enlarged to 92.1 millimetres and, whilst the maximum power remained the same as before, the torque was increased, as was the flexibility. However, you cannot go on indefinitely making an established engine bigger and bigger in capacity: it is more than likely that, some time before the limit of feasibility has been reached, the limit of advisability will be passed. This was what happened to the XK engine. The 3.8 had been phenomenal in view of the size of its pistons and the length of their stroke; it was crisp, responsive, tractable, and safe up to 6000 rpm.

The enlarged version of 1965 and the years that have followed was more flexible but rougher in its running, and severely limited by structural considerations so that it could not safely be run at more than 5000 rpm continuously, and indeed was unpleasant beyond 4500. In the E-type, to cruise at those revolutions would have involved going much faster than most drivers were prepared to undertake, so nobody really minded. It was simply assumed that a bigger engine must be better, and people thought it was nice not to have to do so much gear-changing. So much then for Jaguar's long-overdue admission that the Moss gearbox was obsolete, and that their own all-synchromesh device should replace it.

There were lots of other changes too: room was found for taller drivers, brakes were devised that would stop the car properly and radial-ply tyres that improved the ride and promised reasonable durability replaced the high-speed nylon cross-plys that had given the earlies E-types uncommonly good handling characteristics. Of course, people were not content with the two-door fixed-head coupe, the roadster, and the hard-top. The car was very very good - but as it stood it lacked refinements readily available on American built cars.

US customers in particular demanded more comfort, and seats - thus, the 4.2 E-type begat the 2+2 with high roof, steep screen and long wheelbase; and that begat the second series E-type which was a face-lifted variant beginning to suffer, as were all Jaguars and most other cars, from the legislative strictures of American anti-pollution and safety lobbies. The weight was going up and the power was going down, but the car was still a lot faster than most customers would be able to exploit, as in many countries speed limits were being reduced.

The Jaguar V12

The third series was given a new V12 engine of 5343 cc displacement. Made mostly in light alloys, the twelve weighed about the same as the old iron-bellied six. Gone was the hemispherical combustion chamber, its place taken by a Heron-type head with half the depth of the chamber sunk in the piston crown. The valves were worked by a single camshaft above each head, the plugs were sparked by an electronic system built into a big distributor that sat and fried in the angle between the banks, the power was an entirely adequate 254 bhp at 6000 rpm, and the flexibility was outstanding.

It looked a splendid engine, if you could see it; most of the time it was hidden from view beneath the supplementary plumbing for detoxing devices. Its 'devolution' from a four-camshaft racing engine that never raced was a fairly well kept secret for many years, although rumours of a new rear-engined Jaguar sports/racer reached a few ears in the middle 1960s. It was made, and it was beautiful in the Sayer tradition, and it mustered something like 500 bhp, which the designers (Waiter Hassan and Harry Mundy) thought inadequate. It went very fast, but it never raced. In fact, the sole example was written off in a high-speed accident, to be rebuilt later as a showpiece exemplifying all that Milton had to say in his Areopagitica about fugitive and cloistered virtue. So much for the XJ 13, which is what the hyper-sports car was called.

The XJ Series

The XJ Saloon series is much more important: it is the model for which the V12 engine in its production form was intended. Employing the all-independent suspension of the E/S/Mk 10 refined until its ride quality set standards by which anything could be judged, heavily and expensively insulated (as was the engine) by a generously finished body of consummate good looks and unmistakable Jaguar breeding, the XJ saloon was meant to be powered by either the V12 or a curious V8 version of it, but the car was ready before the engines, and went well enough with the 4.2-liter XK engine under the broad bonnet.

Very Fast, Very Thirsty, Very Quiet and Very Smooth

The de-tuned XK engine.was down to 170 bhp, but the XJ would do 120 mph or more despite its formidable weight, and its roadholding on new 70-series radials was as good as the wide track and low build suggested. For those content to motor more gently there was a 2.8-liter version (the stroke was shortened to 86 mm) that managed 140 bhp and looked just as good. So well did the XJ6 sell that there seemed no point in hurrying the XJ12 into production. The V12 E-type was therefore allowed to go before it in 1971; the following year, when at last the flagship was launched, was by no means too late for it to impress all who drove it. Very fast, very thirsty, very quiet and very smooth, it was exactly what all manner of people persuaded themselves they wanted. In 1972 Sir William Lyons retired and took with him, or so it seemed, part of the magic and tradition of Jaguar - that glorious history of which he was part and which was part of him.

The Jaguar XJ-S

The

Jaguar XJ-S was technically superior to the E-Type, and featured an auto transmission and 2+2 seating. Both the front and rear suspension were independent, by coil springs and wishbones at the front, and by a modified E-Type /XJ12 system at the rear. The concept was significantly improved in mid-1981, when the more efficient and more economical 'HE' engine was introduced, the car then becoming known as XJ-S HE. From 1982 the XJ-S began to make its name in production touring car racing, when Tom Walkinshaw prepared two cars for the European Touring Car Championship. Initial success included victory in the Tourist Trophy, after which Jaguar gave official support for 1983 and 1984. Jaguar would go on to score five outright victories (compared with BMW’s six) in 1983, then with a full three-car team went on to win the Manufacturer's and the Driver's (Tom Walkinshaw) series in 1984.

Another variation on the XJ-S theme came in 1983, when Jaguar launched a cabriolet version of the XJ-S featuring a fixed roll-over bar above the seats and a completely new 3.6-liter twin-cam six-cylinder engine good for 225bhp mated to a five speed Getrag gearbox. The 80’s were not, however, halcyon days for the marque, reliability and build quality issues soon tarnishing what had, until then, been such a highly regarded marque. Certainly any pre-1980’s Jaguar are very collectable, however provided you do your homework a 1980’s Jaguar may represent exceptionally good buying. Consider that now most problems should have been addressed, such examples represent a much cheaper entry into what is undeniably a fabulous marque…

Recommended Reading:

Jaguar Car Reviews

Swallow Sidecars - The William Lyons Story

Jaguar - A Racing Pedigree