|

General Motors

|

1908

- present |

Country: |

|

|

William Crapo Durant

General Motors may never have happened had David Dunbar Buick stuck to making bathtubs and U-bends for a living, instead of trying to make money out of the horseless carriage. For, in less than a year, the Buick company, founded in 1903, had become an utter financial failure, and the worried investors were seeking a miracle man who could pull the seemingly doomed company back on to a profitable basis.

Their choice was a 44-year-old Michigan carriage builder, who had little idea of how a car was built and even less of what made it run; it was an inspired decision. The man they selected, William Crapo Durant, was one of that select group of natural entrepreneurs who were to transform America from an agricultural to an industrial nation. Durant, who was born in 1860, came from a family whose fortunes were large enough for him to have lived a life of idleness had he so wished, but young Billy had all the right 'go-getting' instincts and started out to make his own career when he was sixteen years old.

By the turn of the century, Billy Durant had become the head of the biggest cart and carriage makers in Flint, Michigan, America's carriage capital, in partnership with one J. Dallas Dort. He was a natural salesman, and proved it when he took over Buick by selling US$500,000 of company stock in a day. Within three years, the Buick company had an annual production of over 8000 cars in its new home in Flint, and was one of the big four of the infant American motor industry.

Durant, however, had bigger ideas still. He felt that the individual motor company offering a single model line was at the mercy of the buying public and, if they failed to buy sufficient of its products in a given year, that could spell disaster. He reasoned that a consortium of major producers could support each other in times of crisis, as well as organising their own parts-manufacturing companies to ensure that they always had an adequate supply of the right components in the right place at the right time, and at the right price.

So Billy called a meeting of the four leading manufacturers - himself, Benjamin Briscoe of Maxwell-Briscoe, Ransome Eli Olds of Reo, and Henry Ford. It looked as though Durant's proposals for a merger between the four companies was well on the way to fruition when Henry Ford suddenly scuppered the scheme by asking for the $3 million agreed value of the Ford Motor Company in cash; this triggered Olds to ask for payments in gold, too. Of course, Durant, who had envisaged the merger as a gentlemanly exchange of share certificates, could not raise $6 million in real money, and the deal was off. There was, apparently, a second attempt to buy Ford in 1909 but, by then, the price had risen to $8 million cash, even further out of Durant's reach. However, Billy had already decided that he could achieve his dream of dominating the American motor industry without the help of the other big four companies, and by 1908 he had floated the General Motors Corporation of New Jersey, which absorbed Buick by an exchange of stock. It was the first step in a breathtaking essay at empire-building.

Oldsmobile

Next, Durant took over the ailing Oldsmobile company, once the biggest of America's car makers, ' whose sales had plummeted from 6500 in 1905 to 1055 in 1908; then he acquired the Oakland Motor Company, founded less than two years previously. There followed, with bewildering rapidity, the takeover of a further twenty companies, including Elmore, Rainier, Rapid Cartercar, Welch, Reliance, Randolph, Welch-Detroit and Cadillac. That bearded patriarch, Walter Leland, of Cadillac had no intention of trading his company for a mass of share certificates and, like Ford, insisted on cash. The price was $3.5 million, and Durant was given ten days to raise it. When he returned, six months later, the price was up to $4,125,000; by the time the sale had gone through, Cadillac cost $4.5 million.

Durant's madcap spending spree, acquiring companies for their availability rather than their earning potential, could have only one end—it came in 1910.The gold-plated straw that broke the corporate camel's back was the Heany electric lamp company, acquired for $7,131,259 (although only $ 112,759 of this was in cash) on the basis that Heany owned the basic patent covering tungsten-filament lamps, which were then being mooted as a replacement for oil and acetylene lighting. A costly law suit proved otherwise and, although General Motors as a whole had just made a net profit of $10 million, and produced one-fifth of all American cars, the Heany venture killed their chances of raising the much-needed capital. No bank would risk lending money to a man who had just squandered $7 million on a worthless patent, and General Motors needed $12 million to keep in business.

When Durant finally found a bankers' syndicate who would bail him out, the terms were crippling. The syndicate, headed by James J. Storrow, of Lee, Higginson & Company, was prepared to loan General Motors $15 million at six per cent. However, they took $2.5 million of this back as commission, as well as $6 million in General Motors stock. Durant, of course, was removed from control (although he remained on the board); in 1910, unable to stomach his loss in status, Durant resigned. Having bailed out the General Motors Group, the bankers set about making it profitable. At first they thought of axing everything but the two most profitable companies, Buick and Cadillac, but Henry Leland persuaded them to keep the group alive. Even so, there were rationalisations—Rainier and Welch were amalgamated in 1911, to produce a car called the Marquette, which survived only a year, while Carter-car ceased production in 1916 (although its associate company, Pontiac, was revived later).

General Motors building on Brodway, New York, circa 1972.

General Motors building on Brodway, New York, circa 1972.

Thomas A Murphy, Chairman of General Motors Corporation from 1974 to 1980.

Thomas A Murphy, Chairman of General Motors Corporation from 1974 to 1980.

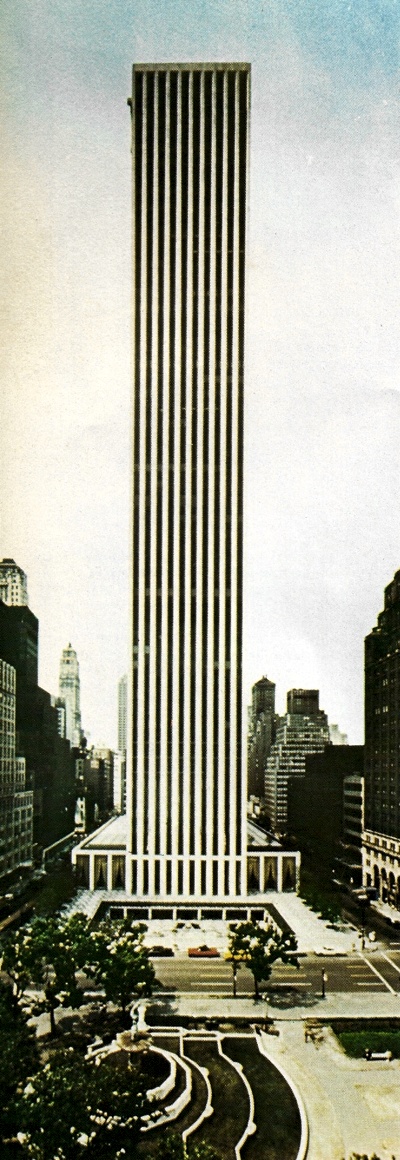

General Motors building on Fifth Avenue, New York, circa 1972.

General Motors building on Fifth Avenue, New York, circa 1972.

GM Chevrolet Caprice Station Wagon, circa 1974.

GM Chevrolet Caprice Station Wagon, circa 1974.

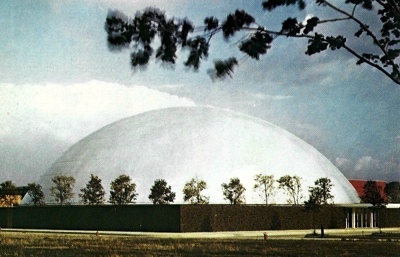

GM Central Technical Studios at Warren, Michigan, circa 1974. The unusual steel dome was almost 4 inches thick, and the building stood over sixty feet high, and was one hundred and seventy feet wide.

GM Central Technical Studios at Warren, Michigan, circa 1974. The unusual steel dome was almost 4 inches thick, and the building stood over sixty feet high, and was one hundred and seventy feet wide.

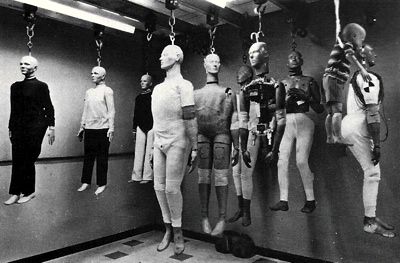

Safety was of growing concern to GM through the 1960's and 1970's.

Safety was of growing concern to GM through the 1960's and 1970's.

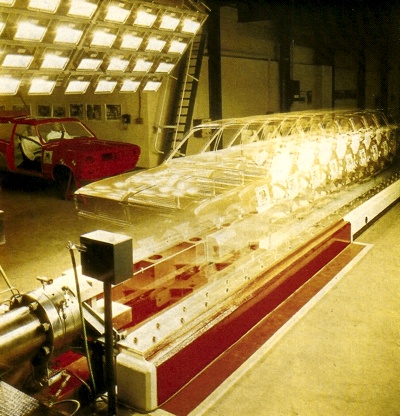

Vauxhall Victor prototype running into a 75 ton concrete block during safety testing at GM's United Kingdom division Vauxhall.

Vauxhall Victor prototype running into a 75 ton concrete block during safety testing at GM's United Kingdom division Vauxhall.

|

The Storrow Syndicate

The Storrow syndicate put in its own nominees at the head of General Motors: Charles W. Nash became president in 1912, while Walter P. Chrysler became works manager. Both men were to make a major impact on the industry in later years as the heads of their own companies. Under their guidance, General Motors made a steady recovery, but they had not heard the last of the indefatigable Billy Durant, the 'Man with the midas touch'. Durant had returned to Flint, and established the Little Motor Car Company on a capital outlay of $26,000, selling 3500 cars in the first year.

Then he launched Chevrolet, which combined with Little in 1913; the success of the Chevrolet launch enabled Durant to seek capitalisation from the rich DuPont banking family. A new company, Chevrolet Motors of Delaware, was incorporated for $20 million—later raised to $80 million—to absorb the old Chevrolet company. Then Durant offered to exchange five shares in Chevrolet for one share of General Motors; the investors responded eagerly. In addition, Durant and DuPont bought up any shares in General Motors which came onto the market. Thus it was, that in 1915 Billy Durant could walk back into General Motors and say: 'Gentlemen, I control this company!'

Nash, who did not share Durant's ebullient vision of the future prospects of the motor industry, resigned; backed by Storrow, he founded the Nash Motor Company, aiming at the more conservative sector of the market. At first, 'Durant's Second Empire' was based on the organisational nonsense that the part was greater than the whole, that Chevrolet, one of the manufacturing companies making up the General Motors organisation, actually owned the parent company. This situation, however, was remedied in 1918 when the General Motors Corporation was created to absorb General Motors Company and Chevrolet, as well as another of Durant's creations, a consortium of parts manufacturers called the United Motors Corporation, which linked such companies as Delco and the Hyatt Roller Bearing Company. It was a move which was to ensure the future growth of the General Motors Corporation, had Billy Durant realised it, for it brought into the company two men who were to play a vital part in shaping the organisation. They were Charles F. Kettering, of Delco, a brilliant research scientist who had perfected the electric starter (he was also a pioneer aviator who had helped the Wright brothers build their power unit) and, more importantly, Alfred P. Sloan, of Hyatt.

The Hyatt company had been founded by John Wesley Hyatt, who had invented celluloid as a substitute for ivory, so that billiard balls could be made more cheaply, and had then turned his attention to the design of tapered roller bearings. Sloan had joined Hyatt on graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but Hyatt proved to be a far better inventor than businessman, and the company was soon in trouble. Sloan's father stepped in with a loan of $5000, which saved the company, and his son took over from Hyatt as president. He acquired control at just the right time, for the motor industry was just beginning to expand, and there was an ever-growing demand for Hyatt roller bearings, which Sloan was ready to supply.

In time, he had built up the Hyatt company to the point where he felt it had become too big to remain independent. Yet when Billy Durant suggested that Hyatt became part of United Motors, Sloan's initial reaction was one of reluctance. Then he reflected on the fact that he depended on orders from Ford and General Motors for the continued existence of his company: should they decide to make their own bearings, he would be out of business. It would be far better to throw in his lot with one of the two giants while he had the chance. So, Sloan joined United Motors and, when the General Motors Corporation was created in 1918, he became a GM vice-president.

As for Billy Durant, he was back in his element; almost immediately he set about a vast expansion programme. The Chevrolet, Buick and Oldsmobile factories were extended, a completely new Cadillac plant was built, while a new headquarters building rose 15 storeys high above Detroit, where General Motors also opened a new research laboratory. Inevitably, there were many more company acquisitions, as if to compensate for the closures under the James J. Storrow regime. For $30 million, Durant acquired the Fisher Body Company which, for once, was an acquisition well worth what General Motors had paid for it; indeed, it has been said that if there had been no Fisher Body, there could have been no General Motors as it is known today.

The Fisher family had been engaged in the blacksmith and carriage-building industries for at least two generations when Fred Fisher came to Detroit in 1902, and found a job as a designer with a pioneer car-body manufacturer. Once he was established, he sent for his brother, Charles; then they asked William to join them. Eventually, the remaining four brothers-Edward, Lawrence, Alfred and Howard—were working in Detroit. Inevitably, they combined to form their own body-building company, in 1908. The Fisher Body Company was followed two years later by the Fisher Closed Body Company, and the two were then merged in 1916 to form the Fisher Body Corporation. All seven brothers stayed on after the 1918 takeover.

Another of Durant's acquisitions was an unsuccess-i ful one-man operation, the Guardian Frigerator i Company, run by Alfred Mellowes, who had built a I refrigerator in Dayton, Ohio, in 1915, moved to I Detroit to market his invention, and sold just 40 electric freezers in two years, losing $34,000 in the process. Durant bought the company for just $56,300, 1 using his own cash for the purchase, and changed its name to Frigidaire; in 1919, he sold the company to General Motors for what it had cost him. 'What is an automobile manufacturing group doing manufacturing electric refrigerators?' queried his fellow directors. 'That is easy,' countered Billy. 'A refrigerator is really very similar to an automobile - they are both boxes with motors inside!'

General Motors Acceptance Corporation

GM broke into the finance field with the formation of the General Motors Acceptance Corporation, which provided hopeful customers with the necessary ' credit to finance the purchase of their new car. However, the good wrought by such innovations was completely nullified by a mistake of typical Durant proportions. Inspired, no doubt, by the success of the Fordson tractor, Durant persuaded General Motors to build a range of tractors and farm equipment. Walter Chrysler, then heading Buick, warned against such a venture, but was overruled. Time was to prove him right for, in 1920, GM closed this agricultural side of their corporate business, having lost $30,000 in a very short space of time. Had the post-war boom in car sales continued, Durant's wild spending might have paid off. As it was, the market suddenly collapsed in the mid-1920s, with disastrous results. Durant had tried to control the affairs of all the conglomerate companies of General Motors personally but, as he devoted most of his time to playing the stock market—he is reputed to have operated at least 70 different brokerage accounts—and either ignored his subordinates completely or else unnecessarily interfered with the way they were carrying out their work, the affairs of the GM corporation were slipping rapidly from his grasp.

Chrysler left in disgust over the tractor episode in mid-1920 while Sloan, equally frustrated, but not ready to resign, worked out a reorganisation plan which he presented to Durant. Billy approved the plan—but did not do anything about it. Sloan realised that Durant was beyond help, and took a trip to Europe to consider what to do next. He decided to resign as soon as he got back to Detroit. But nemesis had already overtaken Durant, whose personal finances were heavily overcommitted, and who had been trying an impossible juggling trick to keep General Motors in business, for the corporation's stock had plunged from S400 to S12 a share. Durant pumped S90 million into the market in a desperate bid to raise share prices, but without success. When Pierre S. DuPont heard that Durant was threatened with bankruptcy, he acted immediately and found that Billy's finances were so tangled that he just did not know where he stood. DuPont and the Morgan banking interests united to save General Motors, and bought out Durant, who held 2,500,000 shares in the corporation, on condition that he resigned.

DuPont, reluctantly, became president, but he was just a figurehead to inspire confidence in the corporation's renewed financial stability. The power now lay with Alfred P. Sloan, the new executive vice-president. 'General Motors had become too big to be a one-man show,' commented Sloan. 'It was already far too complicated. The future required more than an individual's genius.' 'Dictatorship,' he added, 'is the most effective way of administration, provided the dictators know the complete answer to all questions. But he never does—and never will.' In place of Durant's erratic dictatorship, Sloan proposed that, while the corporation should follow a co-ordinated central policy, each of the component companies should operate as autonomous units within that framework. And he was ready to buy the finest talent available to ensure the new regime's success.

A prime opportunity came early in 1921, when William S. Knudsen, one of the top men in the Ford Motor Company, was discharged, apparently for showing too much independence and thus treading on the toes of his fellow-Dane, Charles Sorensen, Henry Ford's right-hand man. For a while, Knudsen managed a Detroit car accessory factory, and then he happened to meet Sloan. There was, in fact, no job available at General Motors for a man of Knudsen's qualifications, but Sloan at once offered him a place on the corporation's general staff. Within just a month, Knudsen had become vice-president in charge of the Chevrolet division. In fact, Chevrolet sales had slumped so badly since World War I, that DuPont had considered abandoning it altogether: from 144,500 cars in 1920, Chevrolet sales had fallen to 75,700 the next year, and the result was a loss of $8.7 million. A group of consulting engineers reported that Chevrolet was no longer competitive, and should be liquidated, but Sloan thought that with lower prices and better salesmanship and engineering, the marque still stood a chance of breaking into the mass market, and he convinced DuPont to override the engineers' report.

Norval A. Hawkins

Under Knudsen's inspired leadership, Chevrolet expanded rapidly; when he took over, in 1922, Ford was outselling Chevrolet 13 to 1. Only seven years later, Chevrolet became America's best-selling car. Another ex-Ford man snapped up by GM was Norval A. Hawkins who, at a reputed salary of Si50,000 a year, reorganised the various companies in the corporation so that their products should not compete with one another, reclassifying the marques into their own distinctive price and style categories, and improving General Motors' financial efficiency. Sloan and DuPont created a centralised budget for the corporation, instituted efficient control over the stock in-hand and co-ordinated retail demand with vehicle production. And, most importantly, Sloan set out to generate extra sales by encouraging people to trade in their cars when they went out of fashion, not when they had worn out. In short, Alfred P. Sloan created the annual model change policy, which hit at his principal rival, the Model T Ford, whose design was virtually immutable, and also countered the effect of second-hand deals on the new car market.

'I determined,' said Sloan, 'that my first job would be to concentrate all effort possible on making General Motors cars the very top in eye appeal, in engineering soundness, and in technological progress'. Under Charles F. Kettering, the General Motors Research Laboratories kept the corporation ahead in the field of technological innovation, some of 'Boss Ket's' more spectacular developments being the reduction of engine knock by mixing tetraethyl lead with petrol and the first successful quick-drying paint finish for cars, conceived jointly with the DuPont chemical interests. This not only cut painting time from hours to minutes, but made it feasible to offer a wide choice of colour schemes, a facility of which maximum use was made by GM's styling wizard, Harley J. Earl. Kettering also developed an efficient two-stroke diesel—and this led to General Motors moving into the manufacture of railway engines and rolling stock, with the acquisition of the Winton Engine Company and the Electro-Motive Corporation in 1930.

Meanwhile, on the car front, Sloan had built up an enviably efficient dealer network. He spent a great deal of time travelling to dealers' meetings and to individual dealerships, sometimes visiting five in a day, creating a close working relationship between the Corporation and its dealers. Helping to cement the bond was the fact that GM offered a 24 per cent discount against Ford's 17 per cent. By 1927, Sloan's reorganisation had resulted in a doubling of General Motors' profits, and the corporation had become one of the ten American companies valued at over S2,000,000,000; it was the only one of the ten that was set up along the lines of the most modern principles of industrial management. Chevrolet, especially, was riding high, with a total production of 700,000 in the first six months of 1927, equalling the output of the previous twelve months. Ford dealers were switching to the Chevrolet franchise, discouraged by the flagging sales of the utilitarian Model T Ford.

Moreover, General Motors was now an international organisation: there were manufacturing plants in Britain and Germany, where GM had taken over Vauxhall and Opel to produce cars suited to the particular requirements of those markets, while sales outlets were operating in 125 countries. Chevrolets were assembled from Canadian-built components in Britain and Copenhagen, while Buicks had been built in Britain since before World War 1. The corporation had moved into a new element in the late 1920s by acquiring a number of aviation companies. Of these, the most successful was Allison, an Indianapolis-based firm which began building aero engines in the 1930s, and became a major producer in this field during World War II. GM also acquired the Fokker Aircraft Corporation and a 24 per cent interest in the Bendix Aviation Corporation. Fokker, later the General Aviation Corporation, was absorbed by North American Aviation in 1933, though GM retained their interest in this company and Bendix until 1948.

Like all the other American car manufacturers, General Motors suffered severely from the 1929 Depression, but this time there was no repetition of the financial scares of the 1920 slump. Under Sloan's guidance, the corporation rode out the storm, and made a convincing recovery. When he retired as president in 1937, to become chairman of the board, GM was building 40 per cent of all the cars made in America, and 35 per cent of world production. Chevrolet was topping the domestic market, and the company also offered the Cadillac, La Salle, Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac marques, as well as GMC and Chevrolet trucks. Sloan was succeeded by Knudsen, who headed General Motors through the war, in which they produced $12,000,000,000 worth of munitions, two-thirds of it made up of items they had never built before. The effort wore Knudsen out, and he died in 1948. The next president, Charles E. Wilson, known as 'Engine Charlie' to distinguish from 'Electric Charlie' Wilson, who headed General Electric, later became President Eisenhower's Secretary of Defence.

By the 1950s, General Motors had 50 per cent of the American market; when the Senate checked out Engine Charlie's credentials for his post in the Eisenhower administration, he remarked with a straight face: 'What is good for the country is good for General Motors, and what is good for General Motors is good for the country'. It was true too, as General Motors then controlled 117 plants over 21 states and 73 cities of the United States. It had seven plants in Canada and could boast assembly, manufacturing or warehousing operations in 33 other countries. Indeed, the massive organisation that Sloan (who lived on well into his 90s) built, had far more money and resources at its disposal than many countries of the world. The corporation diversified into several fields, including aero-engines, diesel locomotives, earthmovers, rockets, electronics, fridges, dishwashers, electric fires and ball-bearings.

By 1958, the divisional distinctions within GM began to blur with the availability of high-performance engines in Chevrolets and Pontiacs. The introduction of higher trim models such as the Chevrolet Impala and Pontiac Bonneville priced in line with some Oldsmobile and Buick offerings was also confusing to consumers. By the time Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Buick introduced similarly styled and priced compact models in 1961, the old "step-up" structure between the divisions was nearly over. The decade of the 1960s saw the creation of compact and intermediate classes. The Chevrolet Corvair was a flat 6-cylinder (air cooled) answer to the Volkswagen Beetle, the Chevy II was created to match Ford's conventional Falcon, after sales of the Corvair failed to match its Ford rival, and the Chevrolet Camaro/Pontiac Firebird was GM's countermeasure to the Ford Mustang.

Among intermediates, the Oldsmobile Cutlass nameplate became so popular during the 1970s that Oldsmobile applied the Cutlass name to most of its products in the 1980s. By the mid 1960s, most of GM's vehicles were built on a few common platforms and in the 1970s GM began to further unify body panel stampings. The 1971 Chevrolet Vega was GM's launch into the new subcompact class to compete against the import's increasing market share. Problems associated with its innovative aluminum engine led to the model's discontinuation after seven model years in 1977. During the late 1970s, GM would initiate a wave of downsizing starting with the Chevrolet Caprice which was reborn into what was the size of the Chevrolet Chevelle, the Malibu would be the size of the Nova, and the Nova was replaced by the troubled front-wheel drive Chevrolet Citation. In 1976, Chevrolet came out with the rear-wheel drive sub compact Chevette.

While GM maintained its world leadership in revenue and market share throughout the 1960s to 1980s, it was product controversy that plagued the company in this period. It seemed that, in every decade, a major mass-production product line was launched with defects of one type or another showing up early in their life cycle. And, in each case, improvements were eventually made to mitigate the problems, but the resulting improved product ended up failing in the marketplace as its negative reputation overshadowed its ultimate excellence. The first of these fiascos was the Chevrolet Corvair in the 1960s. Introduced in 1959 as a 1960 model, it was initially very popular. But before long its quirky handling earned it a reputation for being unsafe, inspiring consumer advocate Ralph Nader to lambaste it in his book, Unsafe at any Speed, published in 1965.

Ironically, by the same (1965) model year, suspension revisions and other improvements had already transformed the car into a perfectly acceptable vehicle, but its reputation had been sufficiently sullied in the public's perception that its sales sagged for the next few years, and it was discontinued after the 1969 model year. During this period, it was also somewhat overwhelmed by the success of the Ford Mustang. The 1970s was the decade of the Vega. Launched as a 1971 model, it also began life as a very popular car in the marketplace. But within a few years, quality problems, exacerbated by labor unrest at its main production source in Lordstown, Ohio, gave the car a bad name.

By 1977 its decline resulted in termination of the model name, while its siblings along with a Monza version and a move of production to Ste-Thérèse, Quebec, resulted in a thoroughly desirable vehicle and extended its life to the 1980 model year. Oldsmobile sales soared in the 1970s and 1980s (for an all-time high of 1,066,122 in 1985) based on popular designs, positive reviews from critics and the perceived quality and reliability of the Rocket V8 engine, with the Cutlass series becoming North America's top selling car by 1976. By this time, Olds had displaced Pontiac and Plymouth as the #3 best selling brand in the U.S. behind Chevrolet and Ford. In the early 1980s, model-year production topped one million units on several occasions, something only Chevrolet and Ford had achieved.

The soaring popularity of Oldsmobile vehicles resulted in a major issue in 1977, as demand exceeded production capacity for the Oldsmobile V8, and as a result Oldsmobile quietly began equipping some full size Delta 88 models and the very popular Cutlass/Cutlass Supreme with the Chevrolet 350 engine instead (each division of GM produced its own 350 V8 engine). Many customers were loyal Oldsmobile buyers who specifically wanted the Rocket V8, and did not discover that their vehicle had the Chevrolet engine until they performed maintenance and discovered that purchased parts did not fit. This led to a class-action lawsuit which became a public relations nightmare for GM. Following this debacle, disclaimers stating that "Oldsmobiles are equipped with engines produced by various GM divisions" were tacked on to advertisements and sales literature; all other GM divisions followed suit.

In addition, GM quickly stopped associating engines with particular divisions, and to this day all GM engines are produced by "GM Powertrain" (GMPT) and are called GM "Corporate" engines instead of GM "Division" engines. Although it was the popularity of the Oldsmobile division vehicles that prompted this change, declining sales of V8 engines would have made this change inevitable as all but the Chevrolet (and, later, Cadillac's Northstar) versions were eventually dropped. In the 1980 model year, a full line of automobiles on the X-body platform, anchored by the Chevrolet Citation, was launched. Again, these cars were all quite popular in their respective segments for the first couple of years, but brake problems, and other defects, ended up giving them, known to the public as "X-Cars", such a bad reputation that the 1985 model year was their last. The J-body cars, namely the Chevrolet Cavalier and Pontiac Sunbird, took their place, starting with the 1982 model year. Quality was better, but still not exemplary, although good enough to survive through three generations to the 2005 model year. They were produced in a much-improved Lordstown Assembly plant, as were their replacements, the Chevrolet Cobalt and Pontiac Pursuit/G5.

Roger B. Smith served as CEO throughout the 1980s. GM profits struggled from 1981-83 following the late 1970s and early 1980s recession. In 1981, the UAW negotiated some concessions with the company in order to bridge the recession. GM profits rebounded during the 1980s. During the 1980s, GM had downsized its product line and invested heavily in automated manufacturing. It also created the Saturn brand to produce small cars. GM's customers still wanted larger vehicles and began to purchase greater numbers of SUVs. Roger Smith's reorganization of the company had been criticized for its consolidation of company divisions and its effect on the uniqueness of GM's brands and models. His attempts to streamline costs were not always popular with GM's customer base. In addition to forming Saturn, Smith also negotiated joint ventures with two Japanese companies (NUMMI in California with Toyota, and CAMI with Suzuki in Canada). Each of these agreements provided opportunities for the respective companies to experience different approaches.

The decade of the 1990s began with an economic recession, taking its inevitable toll on the automotive industry, and throwing GM into some of its worst losses. As a result, "Jack" Smith (not related to Roger) became burdened with the task of overseeing a radical restructuring of General Motors. Sharing Roger's understanding of the need for serious change, Jack undertook many major revisions. Reorganizing the management structure to dismantle the legacy of Alfred P. Sloan, instituting deep cost-cutting and introducing significantly improved vehicles were the key approaches. These moves were met with much less resistance within GM than had Roger's similar initiatives as GM management ranks were stinging from their recent near-bankruptcy experience and were much more willing to accept the prospect of radical change. Following the first Gulf War and a recession GM's profits again suffered from 1991-93.

For the remainder of the decade the company's profits rebounded and it made market share gains with the popularity of its SUVs and pick-up truck lines. Rick Wagoner had served as the company's Chief Financial Officer during this period in the early 1990s. GM's foreign rivals gained market share especially following U.S. recessionary periods while the company recovered. U.S. trade policy and foreign trade barriers became a point of contention for GM and other U.S. automakers who had complained that they were not given equal access to foreign markets. Trade issues had prompted the Reagan administration to seek import quotas on some foreign carmakers. Later, the Clinton administration engaged in trade negotiations to open foreign markets to U.S. automakers with the Clinton administration threatening trade sanctions in efforts to level the playing field for U.S. automakers.

José Ignacio ("Inaki") López de Arriortúa, who worked under Jack Smith in both Europe and the United States, was poached by Volkswagen in 1993, just hours before Smith announced that López would be promoted to head of GM's North American operations. He was nicknamed Super López for his prowess in cutting costs and streamlining production at GM, although critics said that his tactics angered longtime suppliers. GM accused López of misappropriating trade secrets, in particular taking documents of future Opel vehicles, when he accepted a position with VW. German investigators began a probe of López and VW after prosecutors linked López to a cache of secret GM documents discovered by investigators in the apartment of two of López's VW associates. VW, faced with a plummeting stock price, eventually forced López to resign. GM and Volkswagen since reached a civil settlement, in which Volkswagen agreed to pay GM $100 million and to buy $1 billion worth of parts from GM.

After GM's lay-offs in Flint, Michigan, a strike began at the General Motors parts factory in Flint on June 5, 1998, which quickly spread to five other assembly plants and lasted seven weeks. Because of the significant role GM plays in the United States, the strikes and temporary idling of many plants noticeably showed in national economic indicators. In the early 1990s, following first Gulf War and a recession, GM had taken on more debt. By the late 1990s, GM had regained market share; its stock had soared to over $80 a share by 2000. However, in 2001, the stock market drop following the September 11, 2001 attacks, combined with historic pension underfunding, caused a severe pension and benefit fund crisis at GM and many other American companies and the value of their pension funds plummeted.

Also see: Buick History |

Cadillac History |

Chevrolet History |

Oldsmobile History