|

FIAT

|

1899 |

Country: |

|

|

Giovanni Agnelli

Fiat grew from the Industrial Revolution in 1899. Among the first directors of Fiat was a descendant of the general who had defeated the French at the Assietta a century and a half earlier: Giovanni Agnelli was a former cavalry officer. He was also rich, and not without abilities both in business and engineering; but he was no monopolist, either by ambition or birth.

Like most of his friends in the founding board, he was an intellectual socialist; and he had the intelligence and the intuition to see that the future of the motor car in Italy, as elsewhere, was not tied to the luxury market nor to the races in which he was happy for Fiat to participate for so long, but to the mass production of a type of vehicle which would always be utilitarian while offering as much refinement as the fortunes of the people would allow.

Because Agnelli was such a visionary, Fiat has always held fast to this principle and survived to become one of the largest car manufacturers in the world and was, for a time, the largest outside America before the arrival of Datsun. Because of the way 'It has kept faith with the people', Fiat was able to survive, it was able to diversify (without losing sight of its first object) into other kinds of cars, other kinds of vehicles, other kinds of industries.

Aristide Faccioli

There has been a long list of different models to have emerged from the Fiat factory since the 3

½-horsepower machine built in 1899 by first engineer Aristide Faccioli (who was quickly switched to the design of decidedly-odd aero engines). The first of any note, however, was the 1903 12-horsepower which demonstrated that Fiat not only were setting the standards in Italian car design, but had recognised of the importance of export markets.

The Agadir Crisis

As early as 1907 there were troubles in Turin, when the Agadir crisis (The Agadir Crisis, also called the Second Moroccan Crisis, or the Panthersprung, was the international tension sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat Panther, to the Moroccan port of Agadir on July 1, 1911) had its effect in a general recession that struck at the whole European motor industry. Many companies elsewhere collapsed completely, and Fiat was expected to do likewise. More finance had to be found, and a number of the directors had to be 'lost'. Agnelli emerged with credit from all this activity; the company continued to grow.

By 1910, it was three times as rich as its closest competitor (Isotta Fraschini), with a payroll of 3500 men and an annual output of 1698 cars. The troubles were not over, however: in another decade, Italy emerged from World War 1 on the winning side, but not in good health or spirit. Once again, strikes swept the country and Fiat were not excepted: the factory was taken over by a workers' soviet who actually barred the doors against Agnelli and the chief of his technical office, Guido Fornaca.

Fiat 1902 12/16hp.

Fiat 1902 12/16hp.

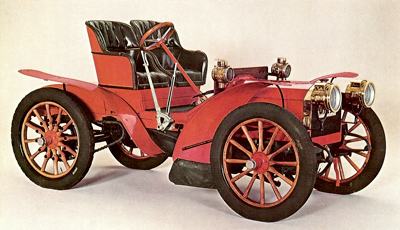

1903 Fiat 16/24hp two-seater runabout, which featured chain drive and wooden wheel rims.

1903 Fiat 16/24hp two-seater runabout, which featured chain drive and wooden wheel rims.

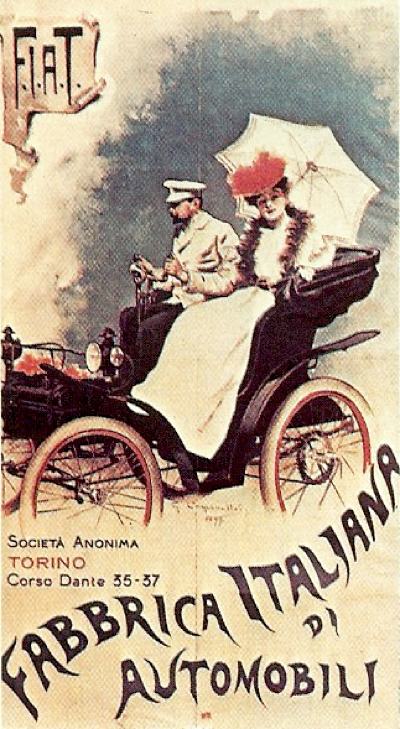

Fiat poster circa 1903.

Fiat poster circa 1903.

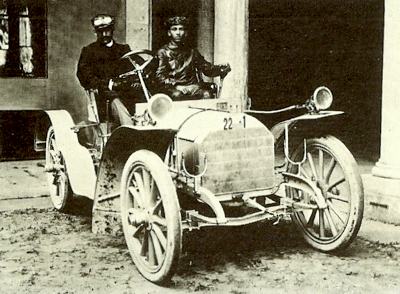

1904 Fiat 24hp Sports.

1904 Fiat 24hp Sports.

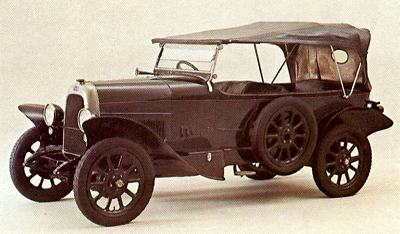

A 1919 Fiat Model 501. This car used a size valve 1.5 liter engine.

A 1919 Fiat Model 501. This car used a size valve 1.5 liter engine.

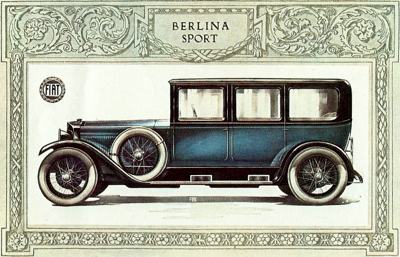

Poster for the Fiat V12 Berlina Sport.

Poster for the Fiat V12 Berlina Sport.

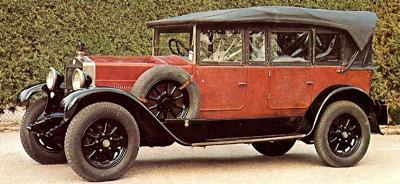

1925 Fiat type 507.

1925 Fiat type 507.

1935 Fiat 1500.

1935 Fiat 1500.

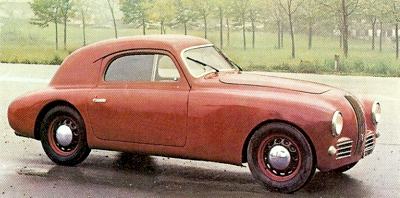

1947 Fiat 1100S Coupe.

1947 Fiat 1100S Coupe.

1953 Fiat 1100 Spider.

1953 Fiat 1100 Spider.

1955 Fiat 600 Multipla.

1955 Fiat 600 Multipla.

1959 Fiat 2300 Station Wagon, powered by a six-cylinder engine.

1959 Fiat 2300 Station Wagon, powered by a six-cylinder engine.

1959 Fiat Ghia 2300 Coupe, powered by a 2.3 liter six-cylinder engine.

1959 Fiat Ghia 2300 Coupe, powered by a 2.3 liter six-cylinder engine.

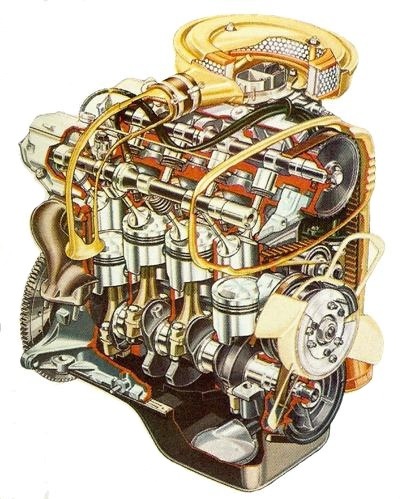

A Twin-Cam version of the Fiat 124 engine, as used in the 124 coupe, 125 and 124 Special T sedans.

A Twin-Cam version of the Fiat 124 engine, as used in the 124 coupe, 125 and 124 Special T sedans.

Fiat Dino with 2.4 liter V6 engine and coachwork by Pininfarina.

Fiat Dino with 2.4 liter V6 engine and coachwork by Pininfarina.

Fiat 125, which used a four-cylinder 1608cc engine developing 100 bhp.

Fiat 125, which used a four-cylinder 1608cc engine developing 100 bhp.

The Fiat 120 Coupe with bodywork by Pininfarina. It was powered by a 3235cc V6 engine developing 165bhp.

The Fiat 120 Coupe with bodywork by Pininfarina. It was powered by a 3235cc V6 engine developing 165bhp. |

There was plenty of speculation as to what the final outcome would be, but the eventual result was that the workers asked the exiles to return to their desks. But Fiat was not successful based on good leadership alone. Many automotive historians believe that, both technically and historically, none were more important than the team who added to their responsibilities the task of producing racing cars for the Grands Prix of 1921 to 1923. They followed no examples and set their own precedents; they did not accept current standards but established new and higher ones; and they stayed on the scene no longer than was necessary to prove their supremacy.

Then they were gone, apparently never again to take an interest in Grand Prix racing, while the fickle world that they had impressed and entertained quickly forgot that Fiat had been the most consistent (and the most consistently successful) participants in motor racing for a whole generation. They began when motoring itself was in its infancy; and, when they left, they had created a series of machines whose principles were to be adopted by many other constructors, and to inspire the design of racing cars and production cars for generations to come. It was not just a case of Fiat's ideas being copied, though seldom have ideas proved to be so widely pervasive.

Carlo Cavalli

Within a year or so of Fiat quitting the motor-racing scene temporarily in 1924 (they did so finally in 1927), its brilliant design teams had broken up, and many of its engineers had found their way into employment with other manufacturers, often with a motor-racing involvement; and so they carried further afield for another ten, twenty, or, in some cases, even thirty years, the ideas that had been prepared and polished in the early 1920s. In charge of them all was Fornaca, frequently described as chief engineer but in fact the head of the technical office in that he directed its policies in the commercial rather than the engineering sense.

Under him as technical director was Carlo Cavalli, trained as a lawyer but inclined to engineering; in 1905, he made the break and joined the Fiat staff as a designer, to play a big part in the design of the heavyweight racers that were successful in the next few years, especially in 1907. He was extremely versatile, applying himself not only to the first shaft-drive cars but also to the first aero engines, to airship engines, marine motors, military vehicles, agricultural tractors and, of course, the brilliant racers. By 1919, at the age of 41, Cavalli had been appointed technical director just in time to assist in the birth of a new generation of cars.

Cavalli had a superb team working under him - Bazzi, Becchia, Bertarione, Cappa, Massimino and Zerbi as design engineers, while in charge of racing-car preparation and team administration was Vittorio Jano. Within a few years, all but Cavalli and Zerbi would have deserted Fiat. In some cases it was simply that rivals accepted that the only way to beat the opposition at their own game was to buy their designers; and so Bertarione and Becchia went to the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq combine. Bazzi and Jano to Alfa Romeo. Next to go was the most senior man under Cavalli, in this case to acquire the dignity of consultative status: Cappa worked for Lorraine, Itala, Ansaldo, OM, Breda, Piaggio, and Alfa Romeo - by that time Massimino too had gone.

The Fiat 801 Grand Prix Racer

It was with three Grand Prix cars that these men made their own reputations, and Fiat's. The Fiat 801 was a 3-liter straight-eight Grand Prix car that presented a complete break away from the prevailing traditions, propounded and established by Henry in the late pre-war years for Peugeot and later Ballot. It had an original engine with two valves per cylinder instead of four, with ten roller main bearings, and even with roller big-end bearings, with a built-up form of cylinder head construction and with an ability to operate reliably at higher rates of revolution and power than any rival. It had a necessarily limited career, as a new Grand Prix formula was due to restrict cars to two liters engine displacement, the following year; but in its appearance at the Brescia Grand Prix in 1921 it proved itself the fastest car, until checked first by a puncture and then by an oil pump failure.

The 1922 racing Fiat was a miniaturised six-cylinder version that confirmed the promise of the three-liter eight by almost pulverising the opposition: at its first appearance, it won the French Grand Prix in 6 hours 17 minutes, after which officials had to wait nearly an hour for completion of the same distance by the first of the three

Bugattis which were the only other cars to finish the race. All other competitors were so discouraged by this performance that they stayed away from the next GP at Monza, preferring taunts of cowardice to proof of ineptitude. Their fears were well founded, as Fiat had uprated the engine to 112 bhp at 5000 rpm, and the cars cruised around to win 6% faster than the only other car, a Bugatti, to finish, and with a lap record 6% faster still.

It was then that the trade in Fiat designers flourished. Two of them went off to build a Sunbeam that the knowledgeable were to describe the next year as a 'Green Fiat'. The trade became practically a black market in 1923 after the appearance of yet another Fiat GP car, this time a straight-eight 2-Iitre with a supercharger - the first GP car ever to be so equipped. It ran into trouble in its first race, the unscreened air intake to its blower ingesting a surfeit of stones flung up from the road but, in modified form at Monza in 1923, it once again put Fiat clearly on top, winning at an average speed nearly 7% higher than that of the six-cylinder car in 1922.

The rush to buy a Fiat designer was topped only by the rush to copy Fiat designs. Nearly every successful Grand Prix car for the next ten years embodied most, if not all, of the 1922 and/or 1923 Fiats' features and, although the developments in chassis design that took place in and after 1934 altered the complexion of racing considerably, engine design still acknowledged the authority of Fiat for decades later. In production cars, the Fiat influence was just as pervasive, and we find Massimino, Jano and Bazzi (all ex-Fiat men) joining Ferrari, Massimo going on to Maserati, Becchia to Lago Talbot, Betarione serving Hotchkiss until the year of his death, 1962.

Tranquillo Zerbi

Depleted though the team might have been, its most brilliant engines man was still there, and still young. Tranquillo Zerbi was born in 1891, studied in Mannheim and worked on diesels before joining Fiat in 1919. He was barely 30 when he conceived the epoch-making blown straight-eight and, when Cavalli eventually had to retire in 1928 through ill health, it was Zerbi who took his place as technical director. In the interval, he had transferred his attentions to aero engines, producing a remarkable series for Schneider Trophy racers and record breakers; but in 1927 he came briefly back to motor racing to try out some ideas in the new 1

½-liter formula.

His first tentative idea was a supercharged opposed-piston two-stroke, but the final car (replete with fascinating and impressive detail in the chassis and bodywork) had a twelve-cylinder engine with its cylinders in two rows on parallel crankshafts that were built up to accommodate one-piece connecting rods, in a manner to be adopted in later years by Auto Union, Porsche, and others. This engine reached a higher bmep at peak power than any before, and was run up to 187 bhp and 8500 rpm on the dynamometer. The car raced once, in the 1927 Milan GP. It won easily, and was never seen again.

Fiat had finished with GP racing and Zerbi was busy again with his aero engines, assisted by Bruno Trevisan who, ten years later, went to Alfa Romeo. in the early years of the century and the formative years of the motor car, when Fiat were nearly always in contention. Their most outstanding year was undoubtedly 1907 when they won all three of the major events - the French Grand Prix, the Kaiserpreis, and the

Targa Florio - each run to a different formula based either on cylinder bore, capacity, or fuel consumption. But there were some Fiat's that were resounding flops: the V12 SuperFiat hyper-luxury car of 1922, the post-war 1400, even arguably the original version of the 132. Either they were the wrong cars at the wrong time, or else they just did not feel like Fiats, in which case there would have to be something wrong with them.

Tracing Fiat Passenger Car Production

There has been a long list of different models to have emerged from the Fiat factory since the 3

½-horsepower machine built in 1899 by first engineer Aristide Faccioli (who was quickly switched to the design of decidedly-odd aero engines). The first of any note, however, was the 1903 12-horsepower which demonstrated that Fiat not only were setting the standards in Italian car design, but had recognised of the importance of export markets.

In 1912 Fiat released their 1.85-liter torpedo-bodied tourer, a light car by the standards of its time, and an important for Fiat, because it was designed to be appealing to the customer, both in looks and price. More importantly, it was designed to be made in large numbers. Unfortunately the project was halted by the onset of World War 1. After the war, in 1919, came the 501, the work of Cavalli, with a four-cylinder, 1

½-liter engine producing 23 horsepower. More than 45,000 specimens were made by 1926, and the car became a legend.

The Fiat 508 Balilla

No Fiat was ever more popular or legendary than the 508, named the Balilla, of 1932. It could be argued that this was the first ever "car for the people": it was compact and light, economical and lively, adaptable to a variety of body styles and to a steady amelioration of individual components. Intended to be cheap as a mass-produced car, its utilitarian aspect was offset (as so often in Fiat's most successful models) by as much refinement as the fortunes of the people would allow: its hydraulic brakes, 12-volt electrics and hydraulic dampers would have been considered luxuries in more expensive cars elsewhere.

The 1937 Fiat 508C Millecente

Its unfashionably short piston stroke heralded the new era of tireless high cruising speeds for the new autostrada. Better still, it had in it the makings of something even more convincing: this became apparent in 1937 when a new 508C was introduced, with independent front suspension, and an enlarged cylinder bore which gave a displacement of 1089cc and attracted the name Millecente (or 'eleven hundred' in the English-speaking markets) - a name which became official in 1940 and stayed in the Fiat catalogues for thirty years.

By the standards of its time, the 1100 was a prodigy in handling, ride comfort, and performance: it was then the only people's car that was also a driver's car. But it was not alone, as its pillarless body suggested, as it looked like a cross between the 1935 1500 and the 1936 500, it was one of a new generation. This was a true impression: those three cars between them marked the emergence of designer Giacosa as one of the greatest benefactors of the motoring world, and the establishment of Fiat as a firm of more national and more social significance than was normally attributed to mere motor manufacturers.

Giacosa's Fiat 500

What distinguished the 500 was simply its size: with a 13 bhp, 569cc engine in a proportionately tiny body (the wheelbase was two good paces), the Topolino was the first really small car to be properly refined and the first to be free from savage compromises of practicality. In 1955, the Topolino was replaced by the rear-engined 600, a four-seater economy and utility car. As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, Fiat developed the largest range of cars in the world. At the bottom of the range was the utilitarian 500 which, with its optional sunroof, was exactly what the Italian public ordered.

Its capacity was upped to 600 cc and it was reclothed in a body that was first seen as one of the many ESVs that bourgeoned when America realised that cars could kill; the 126, as the new car was christened, would take the Topolino theme well into the 1970s. Next came the 127, a simple front-wheel-drive, two or three-door car powered by a 903cc transverse engine. Although otherwise un-distinguished, it became the best selling car in Europe. The 128 too was front-wheel-drive but with an overhead camshaft engine of either 1100 or 1300cc. Variants on the 128 theme came quickly and included wagons, coupes, Rallyes and a choice of two or four-door styling. The 128s were also blessed with a superb chassis which allowed the roadholding potential of tyres to be exploited to seemingly impossible degrees.

The Fiat 124 'Three Box'

More conventionally, 1966 saw the introduction of the 124, a 'three-box' design with a front mounted pushrod engine driving the rear wheels. The following year a similar looking car appeared, the 125. This slightly larger model had a superb twin-cam engine of 1608cc and the option of a sporty five-speed gearbox. The same engine, in 1438cc form, was used in the 124 Coupe - another car with a magnificent chassis. As the Coupe was uprated to 1600cc the roadholding deteriorated and was only revived when the engine was further enlarged, to 1800cc.

The 1970s saw the 124 updated into the 131 Mirafiori, and the 125 into the 132 - with either 1600 or 1800cc engines initially offered and joined by a two-liter option in 1977. Topping the range until the mid 1970s were the 130 series, a conventional saloon and a Coupe which was as beautiful as the 126 was utilitarian. Power for the 130 came from a 3235cc V6 with two camshafts. As well as this basic range Fiat also had some other less conventional models. Fiat built versions of the Ferrari Dino in Pininfarina Coupe and Bertone Spyder forms, differing from their more exclusive cousins in having slightly less powerful engines mounted at the front instead of in a mid ships position.

The Fiat 850 Coupe and Spyder

The 850 sedan was joined by Coupe and Spyder variants and when these were phased out of the range Fiat commissioned Bertone to design a new sports car to fill the gap. The car was the

X1/9 which was powered by a mid mounted 1300cc 128 engine and featured a Targa-type roof. With a low selling price, cheap running costs and good performance it was a natural extension of the range. It was during this time that strikes and absenteeism again made Fiat slide as a automotive powerhouse.

In 1979, the company became a holding company when it spun off its various businesses into autonomous companies, one of them being Fiat Auto. That same year, sales reached an all-time high in the United States, corresponding to the Iranian Oil Crisis. However, when gas prices fell again after 1981, Americans began purchasing sport utility vehicles, minivans, and pickup trucks in larger numbers (marking a departure from their past preference for large cars). Also, Japanese automakers had been taking an ever-larger share of the car market, increasing at more than half a percent a year. Consequently, in 1984, Fiat and Lancia withdrew from the United States market. In 1989, it did the same in the Australian market, although it remained in New Zealand.

In 1986, Fiat acquired Alfa Romeo from the Italian government. Also, in 1986 15% of Fiat company stock was still owned by Libya, an investment dating back to the mid-seventies. U.S. foreign policy under President Reagan's administration canceled a Pentagon contract to produce earth-movers with Fiat and pressured the company into brokering a buyout of the Libyan investment. In 1992, two top corporate officials in the Fiat Group were arrested for political corruption.[16] A year later, Fiat acquired Maserati. In 1995 Alfa Romeo exited the U.S. market. Maserati re-entered the U.S. market under Fiat in 2002. Since then, Maserati sales there have been increasing briskly.

Paolo Fresco

Paolo Fresco became chairman of Fiat in 1998 with the hope that the veteran of General Electric would bring more emphasis on shareholder value to Fiat. By the time he took power, Fiat's market share in Italy had fallen to 41% from around 62% in 1984. However, a Jack Welch-like management style would be much harsher than that used by the Italians (e.g., precarious versus lifetime employment). Instead, Fresco focused on offering more incentives for good performance, including compensation using stock options for top and middle management.

However, his efforts were frustrated by union objections. Unions insisted that pay raises be set by length of tenure, rather than performance. Another conflict was over his preference for informality (the founder, Giovanni Agnelli, used to be a cavalry officer). He often referred to other managers by their first name, although company tradition obliged one to refer to others using their titles (e.g., "Chairman Fresco"). The CEO of the company, Managing Director Paolo Cantarella, ran the day-to-day affairs of the company, while Fresco determined company strategy and especially acted as a negotiator for the company. In fact, many speculated the main reason he was chosen for the job was to sell Fiat Auto (although Fresco fervently denied it). In 1999, Fiat formed CNH Global by merging New Holland NV and Case Corporation.

Partnership with General Motors

Over time, most automotive companies around the world have become holding companies of foreign as well as domestic competitors. For example, General Motors owned a controlling interest in Saab Automobile and, until recently, in Isuzu. Fresco signed a joint-venture agreement in 2000 under which GM acquired a stake in Fiat Auto. This made it appear as if Fiat was next, although GM has made joint ventures with other companies (such as Toyota) without acquiring them. Nevertheless, Fiat did not see the GM partnership as a threat, rather as an opportunity to off-load its automotive business. The agreement with GM included a put option, which held that Fiat would have the right to sell GM its auto division after four years at fair market value. If GM balked, it would be forced to pay a penalty of $2 billion. When Fiat tried to sell GM the company, GM chose the penalty. On 13 May 2005 GM and Fiat officially dissolved their agreement.

The current CEO however views alliances such as these as the deciding factor of the future success of Fiat. In 2005 Fiat was courting Ford. As part of the recent divestitures, in 2003 Fiat shed its insurance sector, which it was operating through Toro Assicurazioni to the DeAgostini Group. In the same year, Fiat sold its aviation business, FiatAvio to Avio Holding. In February 2004, the company sold its interest in Fiat Engineering, as well as its stake in Edison. Fiat faces a multitude of threats, including rising steel prices (up by 16-30% beginning of 2008), a strong Euro, and increased competition from Japanese and South Korean car manufacturers in Europe. Although the light-vehicle market share of Japanese and South Korean automakers in Europe is less than in the U.S. (12.5% and 3.9%, respectively versus 30% and 3.9% in the US), it has been increasing steadily at about a half a percent a year.

Also see: Fiat Car Reviews |

The History of Fiat (AUS Edition)